Misunderstandings can damage your health

Hospitals are full of expert knowledge. But things can still go wrong. Sociologists, psychologists and communication scientists are trying to reduce errors by improving the interactions between doctors, nursing staff and patients.

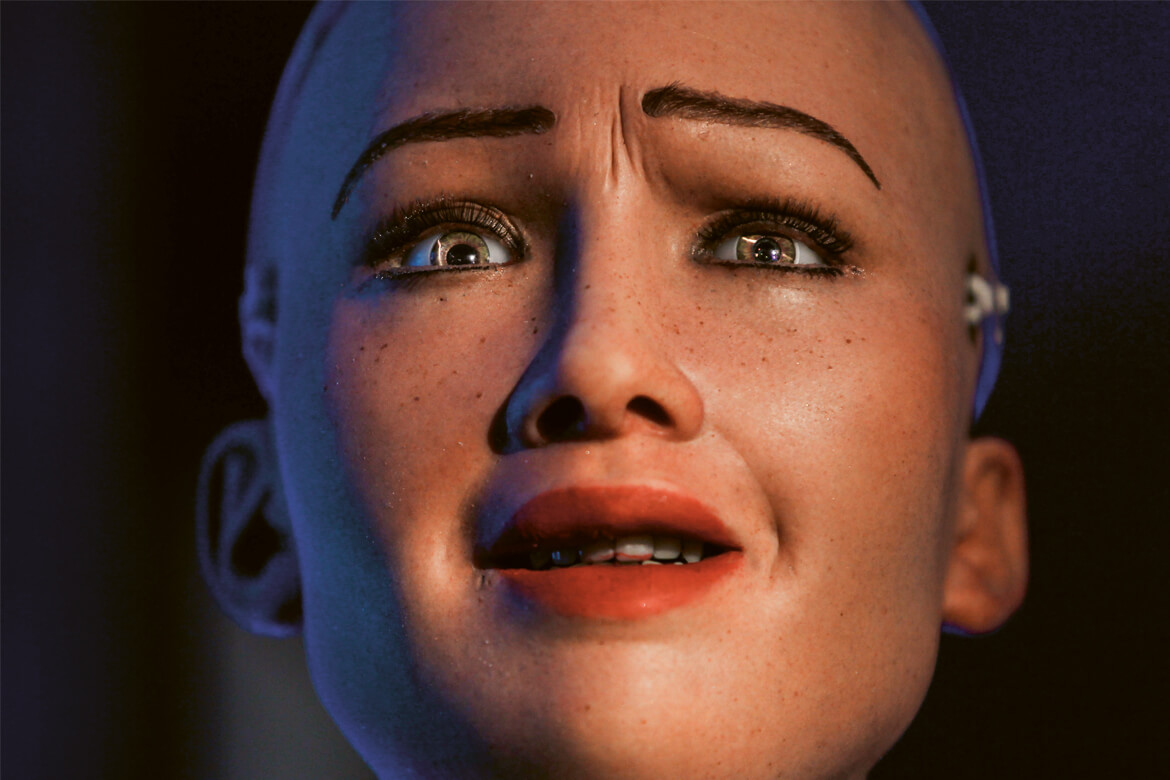

Do patients really understand? Suitable communication strategies and good cooperation among professionals can improve the effectiveness of hospital care. | Image: Shutterstock

It should never happen: in an operation, someone leaves a swab, a compress, or even forceps in a patient’s body. All the same, this occurs in Switzerland in one in every 8,000 operations carried out each year – despite the fact that a precise record is kept of all the material used in the operating theatre. As numerous studies have shown, such mistakes often arise when there are unexpected complications or shift changes in the operating team. And sometimes, it simply happens that no one dares admit that a swab is missing.

“In a hospital, lots of different professional groups work together who each have their own specific expertise”, explains the health sociologist Julie Page from the Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW). For them to work together as a real team and to utilise fully all the knowledge they possess, they have to be well coordinated.

Doctor (leafs through her records): “When did we last test your liver?”Patient (42) with alcohol problems, visiting her general practitioner. This is an anonymised example of everyday life in a clinic. More follow below.

But this inter-professional cooperation doesn’t always work properly in hospitals. In Page’s view, one major reason for this is the gap in prestige between the different healthcare professions: “This tends to prevent discussions between them. From a sociological perspective, these discussions are necessary to bring about improvements”. She admits that hierarchies can’t simply be ignored. “But why should it always be the doctor who makes decisions, and not the nursing staff if the situation requires it?” Page is convinced that fewer mistakes would occur if this were the case. “When people have more of a say in things, they also get more involved”.

Simulating emergency teams

But teams that have to work together in emergency situations need different rules – such as in the trauma room. When it’s a matter of life or death, there isn’t time for those involved to engage in a protracted process of team-building. In large hospitals, the individual members making up a team sometimes don’t even know each other.

The psychologist Michaela Kolbe, the director of the Simulation Center of the University Hospital Zurich, is investigating how teamwork nevertheless functions in such situations. Just like in a flight simulator, teams of doctors and nursing staff use Kolbe’s simulator to train how to deal with trauma patients – such as an accident victim with a blocked airway or a patient with severe post-natal bleeding. These scenarios are designed to be realistic – except that the patient is played by a mannequin. Using observations and video recordings, highly trained simulation instructors discuss with the team what personal assumptions and team dynamics have influenced their actions, and why.

These simulations show Kolbe what factors can hinder successful cooperation: “One of the biggest difficulties is that role distribution is not addressed explicitly. Everyone thinks it’s obvious who should to do what – but then suddenly, it doesn’t seem so clear after all”. This is why Kolbe recommends taking a brief time-out at the start to agree on who is taking on what functions. She also advises teams to take a ten-second pause every ten minutes to rethink everything, especially in stressful situations. “This is counter-intuitive and immensely difficult for clinicians because they think that it costs too much time. But in reality, they gain time through it, because they then make fewer mistakes”.

Patient: “A spot? What does that mean?”

Doctor: “Probably cancer, but we’ll first have to do a histologic examination”.

Patient (seems shaken, looks at the floor).

Doctor: “I suggest making an appointment with pneumology. They’ll see how we can best approach the tumour and take a tissue sample. Shall I try and get you an appointment next week?

Patient: “What appointment?” Routine check-up for a smoker (53)

But there is another important reason why mistakes happen in hospital – and not just in emergencies. “Often, team members say nothing when they notice a mistake or don’t understand an instruction properly”, says Kolbe. “The hurdles to open communication are immeasurably high in hospitals”. This is why, in her opinion, team leaders have to make it clear that speaking up is desired: by explicitly urging their colleagues to do so and by reacting positively when someone actually dares to do it.

It’s difficult to put a figure on the impact of this simulation training, because many other factors are involved. But surveys have proven to Kolbe that the participants put into practice the insights they gain in the simulations. For example, according to paramedics, transferring trauma patients to the hospital team has become more orderly and efficient. And at the University Hospital of Basel, a comparative study led by Sabina Hunziker has shown that medical students carry out resuscitation more effectively when they are given instructions about coordination and guidance above and beyond the necessary technical information. The impact of these instructions also remains noticeable for several months afterwards.

The Internet makes for exhausting patients

Trauma patients aren’t in a position to take decisions about their treatment, nor how they are operated on. But the situation is different in the everyday life of a hospital. “For many decades now, there have been endeavours to place the patient at the centre of things”, explains Peter Schulz, a communication scientist who is the director of the Institute of Communication and Health at the Università della Svizzera italiana (USI). Above all, this means that doctors shouldn’t go over patients’ heads when they make decisions, but should instead draw them into the decision-making process. A meta-study that Schulz carried out with colleagues has shown that this so-called patient empowerment can have a thoroughly positive effect: “When patients are actively drawn into the decisions made about them, it has a positive impact on their degree of satisfaction and the state of their health”. All the same, the effects measured are relatively minor.

Patient: “Sure”.

Doctor: “Does anyone have a history of cancer?”

Patient: “Yes, my mother died of breast cancer a month ago”.

Doctor: “Hmm … are there any other cases you know of?” The doctor asks for the medical records of a patient (37) with stomach pain.

This is why Schulz is interested most of all in the conditions under which patient empowerment functions. One of the most important prerequisites for it to work is that the patients possess the necessary competence in health matters – in other words, they should be able to get information about health and illness, and to categorise it properly. But this is not always the case. A study carried out by Schulz has demonstrated that many older people feel overburdened by it. Roughly a fifth of all the elderly people interviewed would prefer doctors to involve them less in their decisions, and to adopt more of a paternal role.

Schulz also says that too much patient empowerment can even be dangerous – for example, when patients overestimate their own medical knowledge. “It’s primarily through the Internet that patients get hold of incorrect or contradictory information, and then they want to act against the advice of their doctor”. When patients arrive with incorrect information like this, it can prove too great a burden for their doctors. Some of them react angrily, while others let the patients do what they want. This is why Schulz thinks it’s important for doctors to learn how to converse with patients in such situations.

Conversation skills for doctors

“Engaging in a patient-centred consultation doesn’t mean that the patient ‘wins’”, confirms Wolf Langewitz from the University Hospital of Basel. He is a professor emeritus in psychosomatic medicine and medical communication and the author of numerous publications on how to structure a successful patient consultation. And he’s not just concerned about making sure the patient is satisfied at the end of it. What’s also important is that the doctor gets all the relevant information from the patient, and that the patient understands the doctor’s instructions correctly. “This is why doctors cannot simply abandon their stewardship of the conversation or their responsibility for it, simply by saying they want to put the patient at the heart of their efforts”.

Langewitz also recommends that doctors should define the content and timeframe of the consultation together with their patient, right at the beginning. Within this framework, the patient is then given the space to raise his or her concerns and worries. Doctors can use various conversation techniques to support their patients in this. For example, brief, conscious pauses in the conversation can encourage the patient to explain more. Briefly repeating what they’ve said can serve to confirm that the doctor has understood everything correctly, and that the patient has nothing more to add.

Doctor: “We’ve increased the Triatec, that’s why your pulse has increased a little more. We’ll have to see how you cope with that. It can go well and it will relieve your heart, or it can have a medium impact and you’ll have some side-effects, or it can go badly, then we’ll know you can’t take the higher dose at all. We’ll have to see how your blood pressure and pulse behave. Then there’s your weight. You know it’s really important to us, for your heart and for being able to halt the drugs. But you can already start to walk about the corridors now. Not much can happen. Just ring the sister if you get dizzy”.

Patient: “Well, can I go home or not?” A hospital doctor speaks with a patient (72) suffering from heart failure.

In many medical faculties in Switzerland, aspiring doctors are now being trained to communicate with patients. Langewitz helped to design the compulsory programme for medical students in Basel, and besides studying the theory of conversational techniques and carrying out simulated conversations with actors, the students learn how to convey bad news in a professional manner. However, Langewitz regrets that this training isn’t continued after graduation: “It’s a sad fact that only a few hospital departments have obligatory communication training”. Because even experienced doctors, nurses and therapists can learn new things in this field. This is illustrated by the Swiss Paraplegic Centre in Nottwil, where regular communication training and supervision among the executive staff has led to an improvement in patient satisfaction rates.

Yvonne Vahlensieck is a freelance science journalist who lives near Basel.