Precision: a gateway to new worlds

The kilogram has to become more stable. Swiss researchers are participating in a worldwide project to provide a new basis for this unit of measurement. And a philosopher answers the question: are there ever limits to precision?

The prototype kilogram has had its day: from November 2018, the whole International System of Units will be defined by the physical constants. | Illustration: Nadja Stadelmann

‘Metre’ means both a measurement and an ordered rhythm in poetry. It came about, ironically, at an immeasurably disordered time – in the wake of the French Revolution, when many different, local units of measurement were replaced by a global decimal system. Napoleon and colonialism ensured that it spread across Europe and throughout the world.

In November 2018, another revolution will come about. The kilogram is going to be redefined, and the Swiss Federal Office of Metrology (METAS) is participating in the process. Its ‘Kibble balance’ (also known as a ‘watt balance’) will enable the kilogram to be measured more constantly over time.

This precision is one of the reasons why the natural sciences have a dominant role in science today. Economists define precise economic indicators, psychologists measure love, and literary scholars quantify words. But can one really do this? And are there limits to it all? The philosopher Oliver Schlaudt offers us some answers.

And yet it changes!

The prototype kilogram stands under three glass bells in a cupboard in the cellar of the Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (BIPM) near Paris. This small metal cylinder, made of 90 percent platinum and 10 percent iridium, has been taken out three times since 1889 and compared with the national copies that were transported to France for this purpose. The experts found that the copies on average had gained 50 millionths of a gram. Or had the prototype lost weight instead? No one knows for sure what happened.

In October 2011, the metrologists of the BIPM decided to address this untenable situation, and redefine both the kilogram and the whole International System of Units. Experimental methods will in future be used to ensure that the kilogram can be reproduced independently, anywhere in the world. Official confirmation is planned for November 2018.

The system is being turned upside down

It’s not just the kilogram that has problems. Electrical engineers have also been working for a long time on their definition of electrical current (amperage). This too will be taken up into the International System of Units.

This System will in future be based on the physical constants. Instead of measuring them with the seven defined units (metre, second, kilogram, ampere, mole, kelvin and candela), the physical constants (c, Δν, h, e, NA, k, Kcd) will be determined once and for all. In future, the units will be derived from them by experimental means.

For measuring the kilogram, two methods have been devised that fulfil the requirements of precision and stability: the Kibble balance and the Avogadro project. The unit of the kilogram will in future be determined by these procedures, using the Planck constant h – in one case by means of the Avogadro constant NA.

How much electricity does a kilogram weigh?

One of the world’s five Kibble balances stands in the Swiss Federal Office of Metrology (METAS) in Wabern near Bern. Instead of comparing the weight of METAS’s national copy with the prototype kilogram in Paris, this complex instrument measures the electromagnetic power that’s necessary to compensate for the gravitational force of the comparative mass.

This mass is held by a coil situated in the field of a permanent magnet. The metrologists then measure the electricity that is needed to induce a magnetic field in the coil sufficient to hold the mass in place.

Using the electricity and the Planck constant h, the experts can calculate the weight of the METAS kilogram down to twenty micrograms. The degree of uncertainty is thus in the same realm as a comparison with the prototype kilogram, but the value measured is more stable – and there’s no need to transport the national copy to Paris.

22 trillion atoms

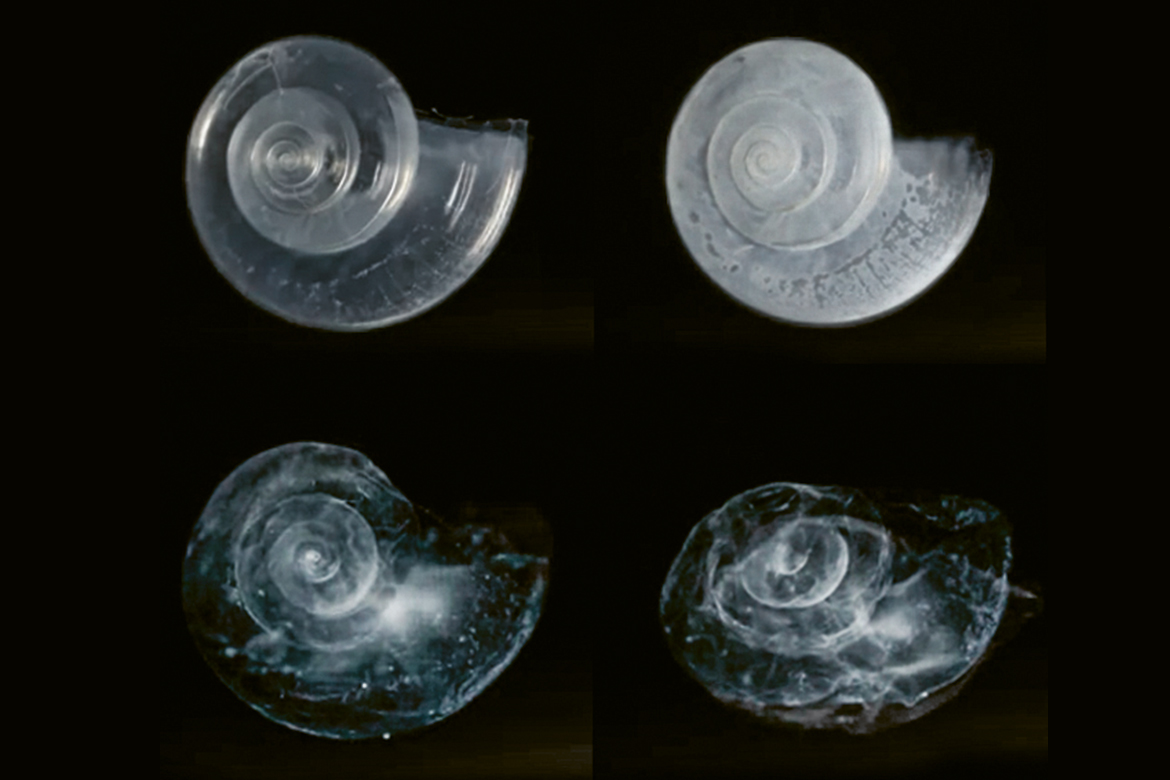

A lens grinder has ground two near-perfect spheres made from a silicon monocrystal. If you were to expand them to the size of the Earth, the difference in height between the highest mountain and the lowest valley would be less than five metres. This material is a silicon-28 isotope that is 99.9995 percent pure and was concentrated in ultracentrifuges.

Now the technicians just have to count the roughly 21.507645 × 1024 atoms. Using X-rays, you can see how tightly packed the atoms are in the crystal, then you can calculate how many there are in the whole ball. Because the mass of a 28silicon atom is known, it allows us to determine the Avogadro constant NA. This in turn allows for an alternative means of determining the Planck constant h.

“Many people think it’s scandalous to compare things with each other”.

The philosopher Oliver Schlaudt is investigating how natural scientists, economists and all other scientists quantify the world. He studied physics, and lectures both at the University of Heidelberg and at the Institute for Political Studies ‘Sciencespo’ in Nancy.

Is there any point in measuring emotional phenomena such as love?

Your question itself testifies to a deeply rooted unease about measurements!

So you say it’s possible. But where does this sense of unease come from?

On the one hand, there’s the matter of objectivisation. It’s unpleasant to be confronted with facts. It’s like going to the doctor: once you’ve got your diagnosis, you have to live with it. The real problem with measurements is that it means comparing one thing with another. But this actually happens all the time in everyday life. Someone might prefer autumn to summer, or we might find one author more subtle than another. The only difference to how it’s done in science is the degree of precision that scientists use to quantify things.

Is there anything that we should never measure on principle?

There we have it again, this unease about measuring! We want to draw boundaries. Even when we’re just talking about things, we start to compare. We need everyday concepts, but these can’t do justice to the individual. If I call you a journalist, I’m comparing you with others. Or if I speak of the French Revolution, I’m making it just one revolution among many. And we’re back to our problem again.

Does this unease also surface in our attitude to efficiency indicators such as university rankings?

This is more of a technical problem, because the measurement criteria are unknown. Excellence and innovative strength are very vague concepts. These criteria are difficult to define, so you inevitably measure the wrong things and create misplaced incentives. The Swiss economist Mathias Binswanger has demonstrated this very neatly.

So measuring just means comparing things with each other?

Yes, for practical purposes. The first measurements occurred in ancient Mesopotamia. Even before they had numbers, practical matters had to be regulated in legal terms across their large, centrally organised empire. So they had to start measuring things. Mathematics later developed out of this.

In what ways do researchers go beyond our everyday comparisons?

In matters of precision. That is fundamental. But it’s not simply about taking something to the tenth decimal point. It’s about opening up a gateway to whole new worlds. The microcosm and quantum physics only become visible thanks to very precise measurements. That’s really a qualitative step.

So are the observing sciences less objective?

Well, their observations aren’t just carried out by anyone, anyhow. Ethnologists don’t just march up to a foreign culture with their photo camera. They are instructed precisely in advance, they compare their observations and thereby engage in a conscious process of objectivisation. What’s special about measuring as opposed to observing is not the act of objectivisation, but the precision that allows the whole panoply of mathematics to be applied to it.

Is there measurement envy on the part of the humanities towards the exact sciences?

I think so. The natural sciences have become our dominant culture. They define what good science is supposed to be. Measuring is one aspect of that. But as I said: even the humanities engage in comparisons. But they specify less precisely how this happens. They’re more concerned with the authority of the trained intellect.