When should farmers plant which crops, so that drought won’t ruin their harvest?

Heat and drought are doing major damage to agriculture. In order for farmers to know when to plant which crops, researchers are developing forecasting models that take both the climate and local farming practices into account.

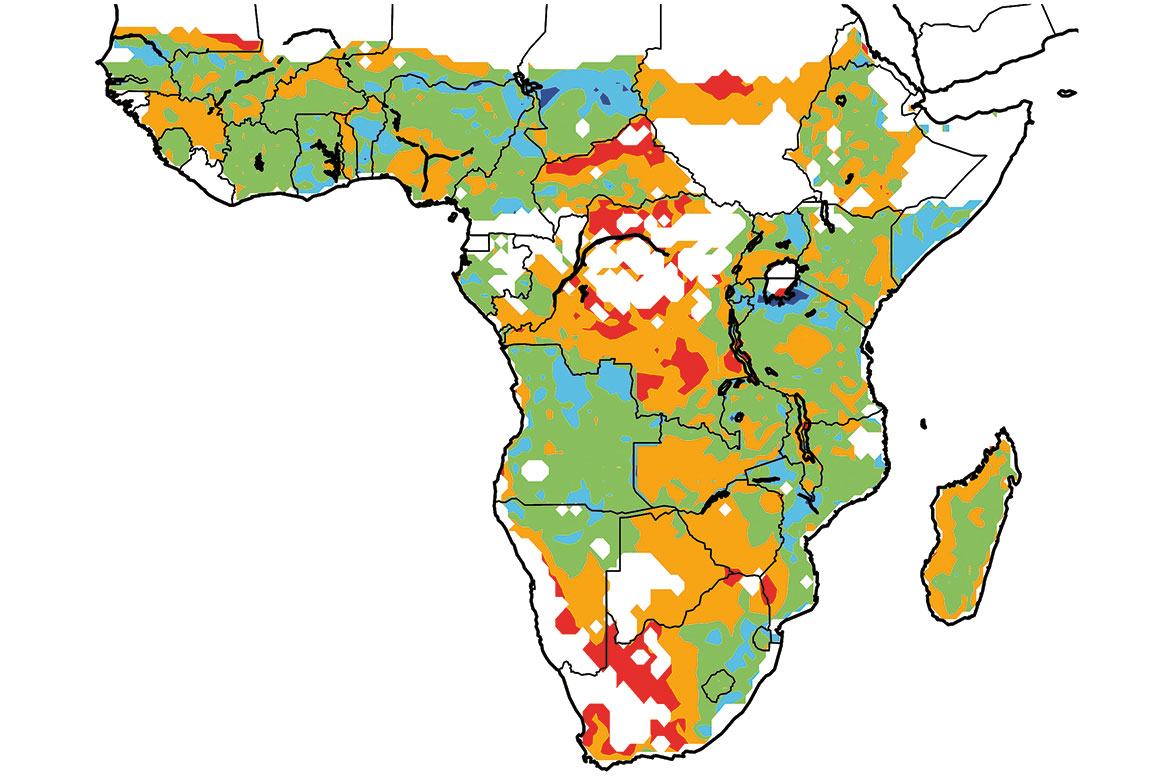

The maize harvest is most endangered in the regions marked red. In the Sahel zone and in the south of the continent it’s too dry, while in Central Africa it’s too hot. Image: Bahareh Kamali/Eawag.

We have less snow in the winter, longer dry periods in the summer, and water is getting scarcer. This scenario doesn’t bode well for farmers. In July 2018, for example, the canton of Thurgau banned the drawing of water from streams, rivers and ponds.

This is why the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) and the Swiss cantons have set up several pilot projects to coordinate water usage and to adapt agriculture to these shifting conditions (details available here, in German only). Among other things, they are drawing up maps of areas at risk of water shortages, and making ten-day prognoses to optimise irrigation.

But the situation in Africa is even more difficult. “With climate change and the projected intensification of extreme weather conditions, the situation is expected to worsen in most countries in Africa”, says Hong Yang of the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology in Dübendorf (Eawag). Together with researchers from several Swiss universities, Yang has now developed a drought vulnerability index linking drought exposure with crop sensitivity in sub-Saharan Africa.

The researchers chose maize for their case study, which is a widespread crop in Africa. They incorporated different data in their model, for example data on agricultural practices – such as when the crop is planted, when it’s harvested, and whether or not fertiliser is used. Then they added geographical data, such as slope and elevation, soil information, and daily climate data such as solar radiation and precipitation. The sources of their information are the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

This enabled them to divide up the whole of sub-Saharan Africa into small regions of roughly 50 square kilometres each, in which they could determine what factors were the biggest threat to the harvest, and where. For example, it rains rather too little in the Sahel and in the south of the continent, whereas in Central Africa it is generally the high temperatures that are the problem, because more water evaporates through the leaves of plants.

Yang admits that their work is complicated and highly theoretical, but insists that it is very useful: “We want to develop a consistent way to measure the degree of crop vulnerability. Although there are many discussions on drought vulnerability, there is little study on how to quantify it”.

Information centres are needed

But can anyone really profit from the results of this model? Chinwe Ifejika Speranza, a professor of geography at the University of Bern, offers a qualified answer: “‘Yes’ at the national planning level, but ‘no’ at the local level. More detailed and context-specific data is needed for such applications at farm level”. In developing countries, the main factors are usually the social and economic conditions of the local farmers. “For example, farmers may receive early warning information but still won’t change their planting dates. Maybe they haven’t the money to buy the right seeds, or have no trust in the early warning system”.

If farmers are going to integrate this new knowledge in their daily lives, they’ll need contact with local, practically oriented researchers and agricultural advisers as well as with the theoreticians behind the simulations. This is why Pierluigi Calanca from Agroscope (the Swiss centre of excellence for agricultural research) is interested in the work of Hong Yang. As they link drought exposure with crop sensitivity, “her ideas are suitable for discussing the vulnerability of production with local stakeholders. They enable you to separate the influence of the climate from the impact of crop sensitivity”.

But this can also function in Switzerland. Calanca has been involved in several pilot projects at FOEN. He sees agricultural information centres – whether public or private – as the ideal places for researchers, farmers and advisers to exchange ideas on cultivation strategies. “Ultimately, it’s personal contacts that are needed”.

Florian Fisch is a science editor at the SNSF