Feature: Rationalising emotion

“Emotions are not universal, but are determined by morals and socialisation”

Fear is no longer linked to feelings of shame. On the contrary, we encourage children to talk about it. But disgust is even more laden with taboos than it used to be. The historian Bettina Hitzer explains in this interview how emotions have changed over time.

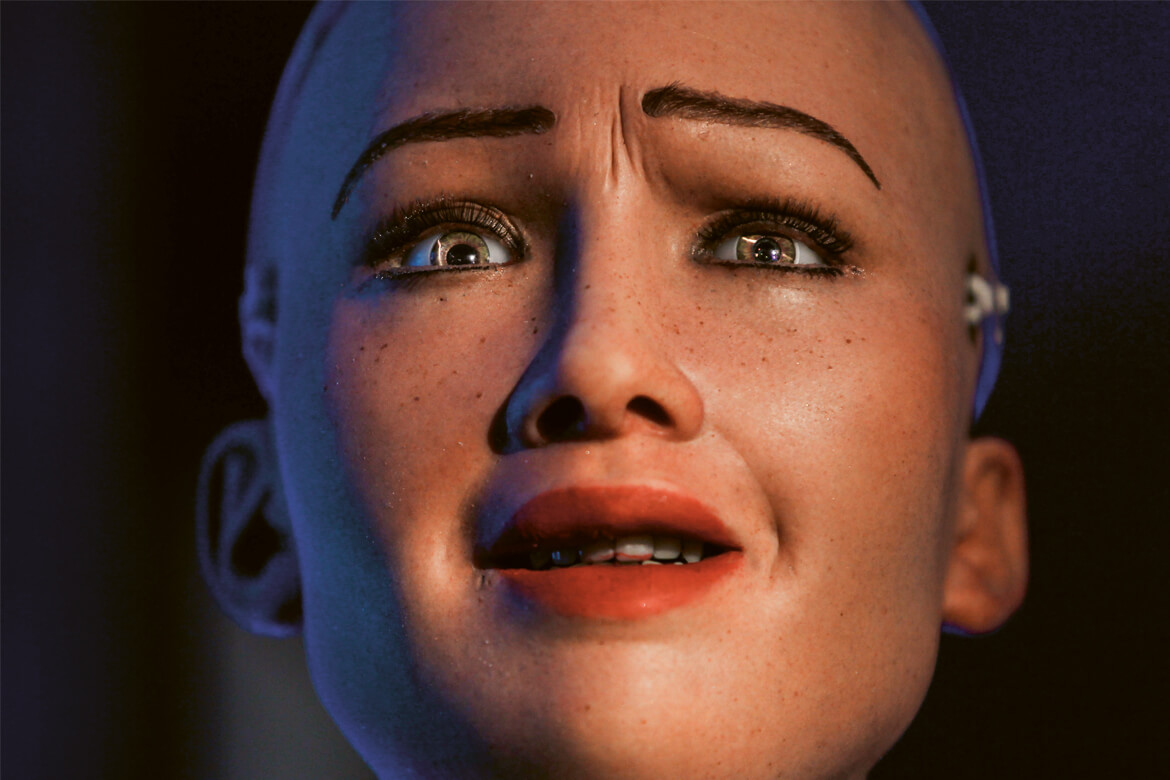

In the late 1960s, scientists first recognised that it’s emotions that actually make decision-making possible, says Bettina Hitzer, who runs the Minerva Research Focus ‘Emotions and Illness. Histories of an Intricate Relation’, a project of the Research Centre ‘History of Emotions’. | Photo: Saied Sharifi

For the past ten years, the history of emotions – especially of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries – has been a research topic at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development. The researchers there want to trace the societal norms that shape our emotions, and demonstrate how emotions have altered over the course of time. Bettina Hitzer runs the project ‘Emotions and Illness. Histories of an Intricate Relation’ and has been involved with the Institute’s emotion research right from the start.

Bettina Hitzer, are people’s feelings different today from 100 years ago?

Yes, I’m convinced of it, even though psychologists and neuroscientists like to argue that emotions are a universal constant. That might be true in terms of neural activity. But for me as a historian, emotions only exist when they are perceived by their subject. And this is where the cultural and historical context comes into play.

How can an emotion change?

People say that fear makes sense in evolutionary terms, because it warns us of danger. But then the objects of our fear change. In the late 19th century, for example, many people were afraid of being buried alive. Today, people tend to fear that brain death will be diagnosed and organs removed for transplantation, even though we might still be conscious in some way. This change has to do with technological developments. But the emotion of fear itself has also changed, because not only has the manner in which we evaluate it in moral terms changed, but so has the manner in which we talk about it. This, in turn, has an impact on the emotion itself.

How is that?

As educational guides from the late 19th century prove, the dominant opinion at the time was that a well-brought-up child with a good character would easily overcome certain fears – such as a fear of the dark – without needing much help. If this didn’t happen, then the child would be ashamed of it, and would do everything possible so as not to speak of it. But this could make his or her fears all the greater. Today, this stance has changed completely, at least in Western society. We even encourage children to speak about their fears. Fear is far less burdened by shame.

We often read that parents used to grieve less on the death of a child in the Middle Ages or the Early Modern Period.

There are in fact many sources that suggest the opposite, and that speak of great sadness on the part of parents. Nevertheless, this grief will have felt different from today, because it was more natural to experience the death of a child. And people were anchored in specific patterns of belief and thought that enabled the death of a child to be assessed more positively: as the passage of an innocent being now gone home to God. Probably only very few people share such a belief today. It’s almost impossible to answer questions about the intensity of emotions. Emotion history does not measure emotions quantitatively, but investigates qualitative aspects and shows how emotions change.

So emotions themselves change. Have any emotions that used to be important been forgotten today? Or did emotions once exist that we now ignore?

Yes – or at least emotions that remain very much in the background. Ute Frevert, who founded this research field, speaks of “lost and found emotions”. For example, empathy is an emotion that was only invented in more recent times. And in the early 20th century, people spoke far more openly about their feelings of disgust towards things or people. Today, however, disgust is laden with taboos.

Are we too politically correct for this particular emotion?

That’s going a bit too far. If we feel a sense of disgust towards other human beings, it’s regarded as an asocial emotion. This is why it’s often kept secret. But it reappears between the lines, as it were – in linguistic images, perhaps. For example, if homeless people are described in a certain way – such as scruffy and unkempt – then it’s clear to everyone that what’s meant is a feeling of disgust. In the first half of the 20th century, however, disgust was often expressed openly. In the 1920s, doctors didn’t want to put patients with advanced tumours in the ‘normal’ hospital wards, because their bodily disfigurements were regarded as nauseating. They wanted to get them out of hospital as quickly as possible, and often left their families to deal with the problem on their own. At the same time, people discussed relatively openly how they might reduce these feelings of disgust. Today, we rarely see such advanced tumours. With cancer of the mouth or jaw, disgust is still an issue. But doctors and nurses discuss this almost solely amongst themselves, because it’s not something they can really communicate in public.

How much does science affect our emotions?

When we look back at the last 150 years, we can see that science has been very important, especially in the fields of psychology, psychoanalysis and physiology. These sciences have developed models for how specific emotions function, and how we can deal with them better. Just think of the different varieties of psychotherapy, which explain and treat emotions in a very specific way.

Was there ever a time in which the sciences greatly changed how we perceive emotions?

In the cultural sciences, we use the concept of the ‘emotional turn’ to describe something that happened in society and the sciences in the 1980s. Its prime aspect was that emotions were no longer seen as being irrational or pathological. And as a more rational phenomenon, they became more accessible to the sciences. We can also criticise this rationalisation process for making emotions and cognition almost indistinguishable from each other. Initial approaches to treating emotions as a scientific object actually emerged in the late 1960s in cognitive psychology. People realised back then that emotions are actually what make decisions possible. These ideas later entered the realm of positive psychology and the concept of emotional intelligence.

What did the ‘emotional turn’ change about society?

The new social movements of the 1970s and ’80s, such as the women’s movement, the peace movement and the environmental movement, discovered that emotions can be a proof of authenticity. But in the public debates of the day, this also brought them into open confrontation with those whose arguments were characterised by cool rationality and were based on risk calculations or security policy. Emotions were presented as an alternative to a society that seemed to be philistine. One of the major demands made during the youth riots in Zurich in the 1980s was: ‘We want more warmth in this cold city!’.

Meanwhile, much research is underway into emotions. Are the emotions of researchers also important in this?

Yes. As a historian, I’ve been busy looking into the emotional history of cancer, and how it is determined by spatial constellations and technological apparatus. In the 1950s and ’60s, technological developments resulted in the sudden emergence of large-scale radiation equipment. Patients were placed in isolated rooms for this treatment, so it wasn’t easy to find out how they felt. That’s why I’ve been looking at photos of people in such situations and have been trying to imagine how I would feel if I had to lie in such an apparatus. What would my emotions be when this machine envelops me and the slab beneath me moves?

How did this help you in your research?

My emotional response to these images pointed me to certain details that I might otherwise have missed, and that I in fact later discovered in patient files. So my own emotions put me on a certain track, and helped me to become a better historian. And yet, in a second step, I had to reflect on my own emotions and ask myself how much they are actually determined by my own cultural context today.

You’ve been involved with the research project ‘History of emotions’ right from the start. What discoveries have surprised you the most?

At the beginning, I was sceptical about whether researching the history of emotions would go beyond scratching the surface. But in the course of my work, I have realised that it’s not just the so-called ‘ego documents’ that tell us about emotions – such as diaries or letters – but all kinds of sources, such as patient reports, court judgements, photos and so on, even if emotions are not explicitly mentioned. It’s both demanding and enlightening to be able to relate all these different sources to each other.

I’ll close with a personal question: why are you interested in emotions?

First, because it was a blank spot in historiography for a long time, and we’ve been able to understand history better since we started researching into emotions. Secondly, engaging with emotions has made it very clear to me that my spontaneous feelings are much more closely linked to my upbringing and my cultural context than I would have thought. Many emotions I used to regard as natural are not as universal as we think, but determined by our morals and our socialisation.