Migrant pioneers

Italian emigration to Switzerland helped to promote gender equality, as the historian Francesca Falk explains in her new book.

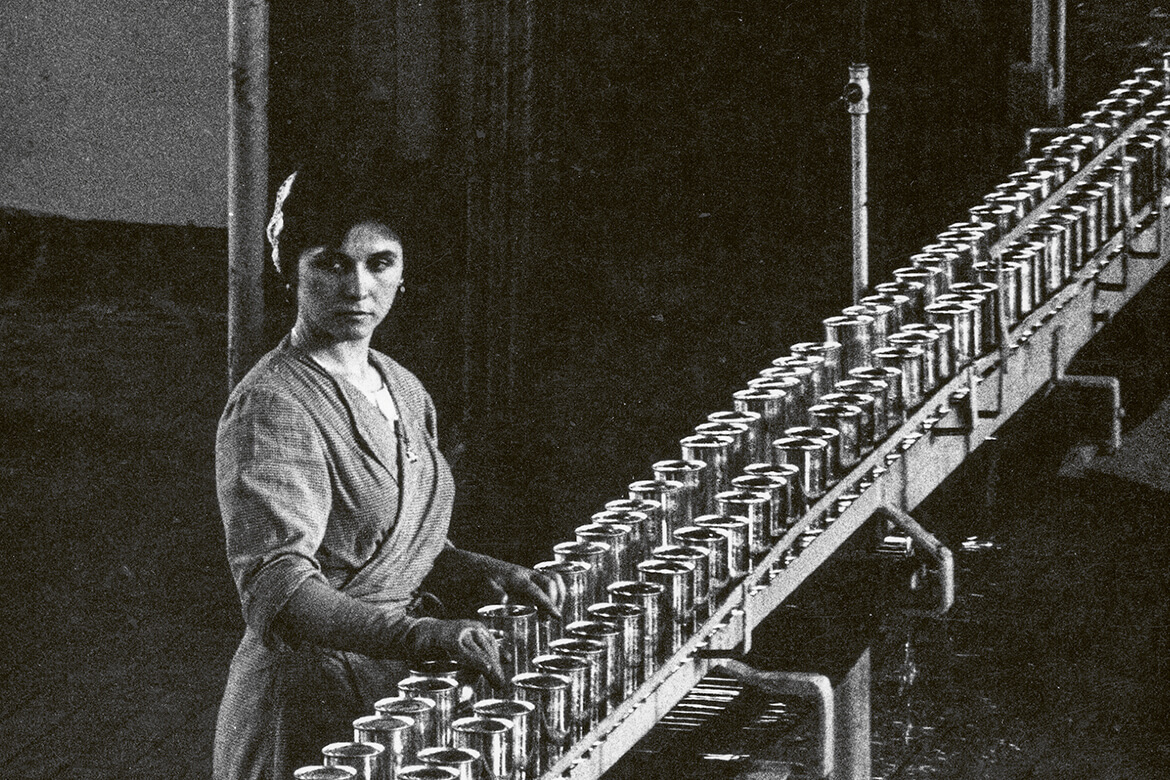

It was common for immigrant women from Italy to work in Switzerland in the 1960s – just as here in the Hero canning factory in 1962. | Image: Keystone/Fotostiftung Schweiz/Hans Baumgartner

When Francesca Falk’s mother came to Switzerland from northern Italy in the 1970s, it seemed like she had travelled back to the past. Her former homeland had introduced votes for women straight after the Second World War, and gender equality was enshrined in its constitution of 1948. But women in her new Swiss homeland still had to ask their husbands for permission if they wanted to go out to work.

It’s almost as if Falk’s research topic at the University of Fribourg was already waiting for her at birth. She’s been investigating the influence of migration on gender equality in Switzerland, and has presented her results in a book entitled ‘Gender Innovation and Migration in Switzerland’.

Looking far across the borders

After the Second World War, the economic boom in Switzerland prompted many people from elsewhere to migrate here, looking for work. Initially, most came from Italy. It was perfectly natural in Switzerland for women to stay at home and look after the children, but in certain regions in Italy – not least for economic reasons – it was normal for women to go out to work. “How to reconcile family life and a career was especially crucial, both to underprivileged Swiss families and to the families of migrants”, says Falk.

We can observe this in the statistics for the city of Bern, where the number of immigrant children in municipal day care centres rose from 60 to 70 percent in the mid-1960s, despite priority being given to Swiss children. And even in the agrarian canton of Valais, immigration ensured that more places were needed in day-care centres. Along with other issues, the infrastructure that emerged ensured in the longer term that external childcare became more and more the norm, also among the Swiss middle classes.

Women who came as immigrants to Switzerland were also among the pioneers for women’s voting rights, alongside Swiss women who migrated within their native country. Iris von Roten, an iconic figure in the feminist movement, was moulded by her experience of migration – she moved from Bern to the canton of Valais, and also spent time in the USA. Many of the first women students in Switzerland came from abroad, as did the first women professors. These included Anna Tumarkin, who originally came from Russia, and in 1909 was appointed the first-ever woman professor at the University of Bern.

Regina Wecker, history professor emeritus, also confirms how migration can act as a driver for societal innovation. She played a decisive role in establishing the discipline of gender history in Switzerland. “Looking out across your borders, and migrating across them, offers an opportunity to expand the horizons of your own solutions”. But at the same time, she insists that the process of anchoring societal change also needed Swiss women who were prepared to be proactive, taking up new ideas and pursuing them.

Migration is neither good nor bad

The cultural historian Walter Leimgruber from the University of Basel also sees the potential of migration: “Basically, every time we engage with other ideas and ways of life, it leads us to reflect on our own societal situation and put it into perspective”. But he feels that gender equality in Switzerland still has a long way to go, such as in financing supplementary childcare. This requires a further critical engagement with traditional role models. “The current discussion about migration shows that we rightly demand gender equality among immigrants, such as Muslims. But in fact we’re asking something of them that in many cases we haven’t yet achieved ourselves”.

Falk also warns that we can’t just regard migration as a success story in the history of societal innovation. “Migration in itself is neither good nor bad”. What matters are the underlying conditions in which migration takes place. And these in turn are influenced by how we approach cases of current and past migration.

F. Falk: Gender Innovation and Migration in Switzerland. Palgrave Studies in Migration History (2019)