The science forager

Gisou van der Goot is a self-proclaimed research nomad. Having grown up on four continents, she is now leaving her mark on life sciences at EPFL. We meet a keen and committed biologist who doesn’t take herself too seriously.

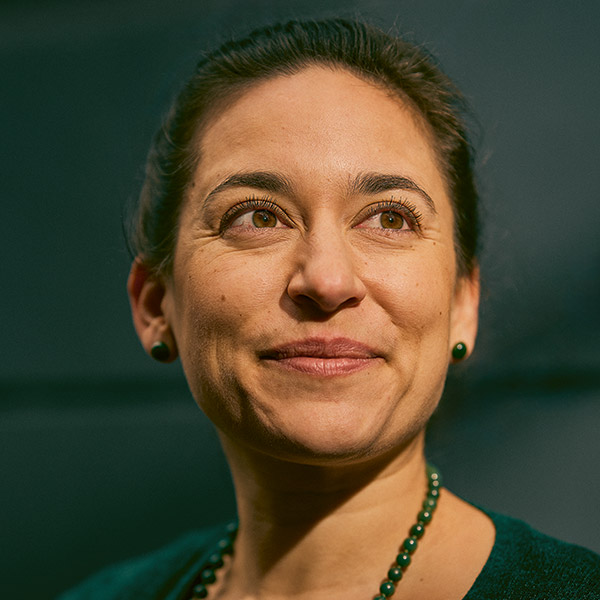

Gisou van der Goot loves biology because of its uncertainties and the questions it raises. | Image: Valérie Chételat

“In science, there are the highly focused researchers who pursue a given goal for years, and then there are what I call pollinators, who move more willingly from one subject to another”, says Gisou van der Goot, laughing. “I belong to this second category”. Now an EPFL professor, van der Goot says she follows her intuition, and it’s worked out well for her. She’s received prestigious prizes for her research in cell biology and has joined the inner circle of deans at EPFL, where she runs the Faculty of Life Sciences.

Van der Goot is a trained engineer turned biologist, a cheerful woman, and a self-defined ‘nomad’ of science. And she knows what she’s talking about: her origins are Dutch, but she spent her childhood in Iran, Egypt, Indonesia and the United States, moving almost every two years due to her father’s job as an agricultural economist at the UN. Having received her education in French-speaking schools and become a “maths addict”, van der Goot enrolled at a faculty of engineering in Paris. With her degree safely secured, she started to hear a voice whispering a warning to her. The risk was that she might “turn 40 and regret not having given research a go”. So she wrote a thesis in molecular biophysics.

Indulging in crisis

Being struck by how “uninspiring” her Parisian laboratory was, van der Goot decided to take a second run at a postdoc at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg. “There I discovered what research was all about. The institute is a real hive of science where you can very quickly do a lot of experiments, and I soon felt at home in this swarm”. It was not only where she met her husband, today a professor of biochemistry at the University of Geneva, but also where she acknowledged that biology was a better fit for her than engineering. “Engineers seek to solve relatively well-defined problems, but biologists, on the other hand, live through a kind of permanent existential crisis. You never know if you’re asking the right question”. She’s unequivocal when asked if she finds that daunting: “I like the quest and I like questioning”.

For several decades now, her quest has been to understand the cell. “It’s a fundamental biological unit capable of compiling entire series of information and reacting to them like a mini-brain, which we’re yet to understand. It fascinates me!”, she says. Meandering down the “river of science” has also led her to develop an avid interest in the host-pathogen relationship. In particular, she is fascinated by several bacterial toxins that use proteins as a gateway to the body.

Fighting prejudice

Unfortunately, society has not always shared her enthusiasm for research, as she herself admits. “It’s not easy in Switzerland to be a career mother”. Anecdotally, van der Goot recounts how she introduced herself one day to the mother of her daughter’s friend, only to receive the response: “But I know who you are! You’re the mother who’s never there”. “That kind of criticism left its mark. No matter how hard you try to protect yourself, it bites”, she says. And her son would ask her, “why aren’t you like other mothers?”, and why she had to travel so often.

“That’s when I discovered the importance of awards”, she says, laughing. In 2009 she received the Leenaards and Marcel Benoist prizes one after the other. “Suddenly an establishment – in this case the media, including local media - had said my work was worthwhile. It changed my private life and the way my children, their teachers and the other parents view my work”.

Having studied engineering, she was already accustomed to being part of the female minority. Nevertheless, she reports never having suffered as much gender-based prejudice as she has since becoming a dean. It was tantamount to being “slapped in the face”, especially in the early days. “At meetings, people who didn’t know who I was assumed I was there to take the minutes ... I can’t blame them, statistically speaking, that is, because there are so few women in management”. Van der Goot strives to facilitate the presence of women and parents in the faculty, including through strong involvement in mentoring young female researchers.

She has also expressed concern about climate change, and wants to call on her colleagues to reduce their intercontinental travel. “Everyone should do something to reduce their carbon footprint”.

Finding safe harbour

Van der Goot does not intend staying long in the dean’s office. “I will stop after my second term, when I have completed the restructuring aimed at professionalising certain roles”. Her nomadic side, however, feels like all the wandering has fulfilled its purpose. “I’m never moving again! There comes an age when you have to stop moving, because you realise the social fabric is what is allowing you to live well for the longest time. Roots are more important once you’re older”. This conviction has led her to refuse management positions in prestigious institutions abroad. “I immediately declined. They must think I’m crazy”, she says, smiling.

However, the wanderlust has not left this aficionado of the Middle East; she dreams most of visiting Afghanistan. But, for now, her work and holidays are enough. “The research community is ideal because you meet a lot of people. In fact, you can travel without having to keep moving. In Switzerland, I live in a village with 1,000 inhabitants while doing high-level science. It’s a luxury”. Either that or it’s the nomad finding the – almost – perfect balance.

Gisou van der Goot was born in 1964 and holds a PhD in molecular biophysics from the University of Paris VI. She is half-Swiss, half-Dutch and, after completing her post-doctoral studies at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Heidelberg, van der Goot joined the University of Geneva at the age of 30. In 2006 she was appointed professor at EPFL and took the reins of the Cell and Membrane Biology Laboratory. Since 2014 she has been Dean of the Faculty of Life Sciences. Van der Goot is married with two children, aged 15 and 18 years.