Feature: Research in crisis zones

When things get dangerous

Whether caught between rebels and their government, entangled in the power structures of unregulated goldmines, or on the terraces with violent football fans – five researchers tell us how they deal with danger in risk zones.

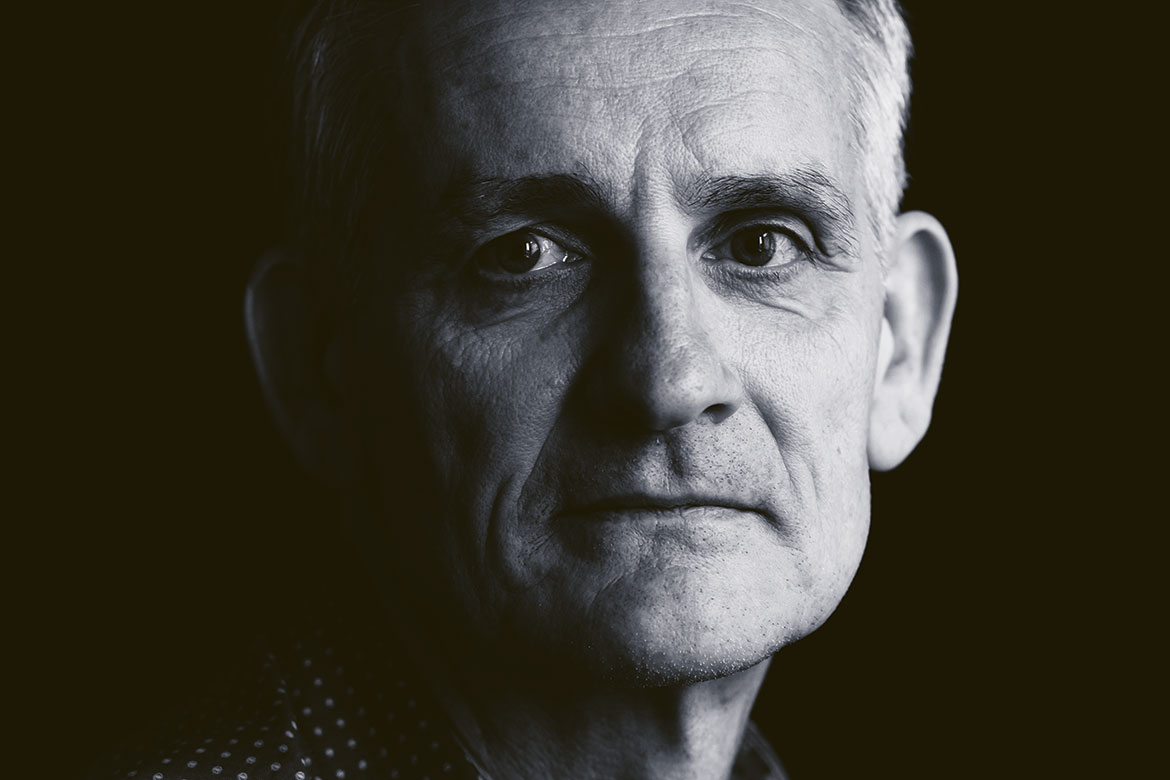

Alain Brechbühl - Institute of Sport Science, University of Bern | Image: Valérie Chételat

SWITZERLAND

“I carry a badge to prove I’m a researcher”

Alain Brechbühl - Research into violence at sports events in Switzerland

“Violence is a fascinating phenomenon, and regrettably part and parcel of our lives. My research hopes to make sports events safer, so my findings are forwarded to partners in the football and ice hockey worlds. I am currently evaluating the ‘good hosting’ concept. The Swiss Football League and its clubs are trying to make visiting fans feel more welcome and thereby reduce the potential for violence. I observe the entrance areas to stadiums and speak to visiting fans during the game.

“The biggest danger I face is that fans can mistake me for a plain-clothes policeman. Attitudes towards the police are really harsh. That’s why I’m as transparent about my work as I possibly can be. If a fan wants to know what I’ve just written down, I show him my notes. I also wear a badge around my neck that proves I’m a researcher. Two weeks before a game, I get permission for my work from the clubs and from the organisers of the stand for the opposing team’s fans. But things do sometimes get a bit precarious.

“Last year, some visiting fans thought I was a journalist, so I had to leave their area. A few weeks ago, it was fans outside the stadium who thought I was a policeman and threw a firecracker towards me. But overall, my relationship to the fans is one of trust. Otherwise, my work would be impossible to carry out”. sj

Aita Signorell - Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel | Image: Valérie Chételat

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

“I had a security briefing with ‘Doctors without borders’”

Aita Signorell - Conducting a clinical study in rebel areas of DR Congo

“The security situation in Congo-Kinshasa is highly volatile. The biggest risks come from diseases. There are repeated outbreaks of cholera and Ebola, for example. I was responsible for a clinical study in the northern part of the country where the security situation was challenging. One research station was in the middle of an impenetrable, densely wooded region where the Lord’s Resistance Army was active. The surrounding villages suffered regularly from brutal attacks and looting on the part of the rebels.

“My work was only possible thanks to a close collaboration with partners on the spot, in particular with Doctors without Borders. Each time, I had a detailed security briefing with the person responsible for the area in question: about the most recent attacks, curfews, and no-go areas. I only travelled in vehicles that had radios and satellite transmitters.

“I was never scared, but I simply didn’t have time for that. Your schedule out in the field is always very tight. But I was always very much on the alert. Difficult circumstances mustn’t prevent us from testing new pharmaceuticals on the spot. And the people there have a right to have their health problems investigated and to receive medical treatment”. sj

Julia Palmiano Federer - Swisspeace Foundation and the University of Basel | Image: Valérie Chételat

MYANMAR

“Western clothing is the best protection”

Julia Palmiano Federer - Peace research on the role of NGOs in ceasefire negotiations in Myanmar

“Although many of my interviews on the peace process in Myanmar took place in a protected environment in hotels, you always felt the presence of a threat – especially for my conversation partners who came from ethnic minorities. It was as if there were something lurking behind you. It takes courage to express your own opinions. I’m researching into the role of mediators from NGOs in ceasefire negotiations: Do their own belief systems play a role in the negotiations? When I meet people, I have to think of the possible risks to them, and ensure that I’m not delivering them up to the government. I’ve spent 18 months doing research in Myanmar, most recently in August 2018 in Mawlamyine. Myanmar is a multi-ethnic state with 135 different ethnic groups – some of which are still armed.

“My research is a risky business. By that I don’t mean the everyday dangers that all tourists know about. It’s the feeling that you might get into difficulty at any time, without forewarning. Once, I went to a meeting with a high-ranking government official in his home, and was accompanied all the way by soldiers carrying machine guns. After several minutes of silence, I began to speak in English, but the local colleague who’d come with me immediately got me to shut up. There was then a hectic discussion that I could not understand. My companion had passed me off as a local, so she could get the meeting. Many people have said I look like a Myanmar national because I was born in Manila, and only later emigrated to Vancouver with my parents.

“In Myanmar, I liked to wear local clothes at first – until one day a man began to harass me angrily when he noticed that I wasn’t a local, despite my appearance. In interviews too, my being unable to understand their language sometimes irritated my conversation partners. The best protection you can get is to wear Western clothes and to speak English – along with my Canadian passport and my working visa. If you don’t have all these, you can easily get into trouble out in the countryside. It can still be dangerous to share your opinions with others in Myanmar. Some of that old Orwellian feeling remains there”. hf

Fritz Brugger - Center for Development and Cooperation (NADEL), ETH Zurich | Image: Valérie Chételat

BURKINA FASO AND CHAD

“We have to understand and respect the local power structures”

Fritz Brugger - Development research on resource extraction in Sub-Saharan Africa

“We are currently working on a project in the north of Burkina Faso, in a region where there have recently been more and more incidents of violent conflict. We are researching into small-scale gold-mining – so-called artisanal mining. The people there prospect for gold without being subject to any control by the authorities. The mines themselves are little more than holes in the ground. People go down through narrow shafts and then come back up with full buckets. They work with picks, shovels and highly poisonous chemicals.

“We are interested in what the gold miners buy with their money. There is a stereotype, according to which the men blow their money on women, alcohol and motorbikes. We want to know the extent to which this corresponds to reality, and whether or not some of their money flows back into agriculture – because that’s the sector where most of the mineworkers originate – or whether they invest their money productively. Parallel to this project, research colleagues are investigating the impact of gold mining on the workers themselves and on the environment.

“As a stranger and a European, you initially encounter scepticism around the mines. The workers assume you’re a representative of a mining company who’s come to claim the area for themselves, or they’re afraid that you’ll report their use of cyanide to the government – because it’s actually forbidden. So you can get a thoroughly unfriendly reception. One major challenge is the chaotic situation you often find on the spot. Up to a thousand people work in the biggest mines. There’s no central organisation, just different bosses with their own shafts and workers. Alongside this, traditional land rights can also apply, and these are subject to their own local authorities. The result is a highly complex network of power structures and interdependencies that is difficult to comprehend.

“This is why we only work with local partners who know the situation well on the ground. They find out who are the main decision-makers, because ultimately it’s them who decide whether we’ll be allowed to do our research. Before this can happen, we always have to have an ‘audition’ before all the influential people. It’s important that the people on the spot understand what our goals are, and how we intend to proceed. They want to be sure that our work won’t threaten their business. After all, they earn their living through it. We can only carry out our research safely if we understand and respect the local power structures.

Bribes create difficulties

“Establishing trust takes time, patience and respect towards the people on all sides. This also applies if children are working in the mines, if workers are being exploited, or if the environment is suffering. We can only carry out our research in earnest if we engage with the people on the spot without prejudice. And trust is something we only acquire on a provisional basis. That’s why, after we’d finished our first bout of research in Burkino Faso, we went back and presented our findings to everyone who had participated. They appreciated that a lot. In Chad, I’ve even met representatives of oil companies informally for meals in order to build up a relationship with them. But there are clear boundaries. It’s not an option to take short-cuts or to pay bribes. That only leads to further difficulties.

“Despite all our precautionary measures, situations can still escalate, especially if we act clumsily or don’t approach a situation with the necessary prudence. I was recently in a region of Burkino Faso where a new gold seam had just been discovered. As if by magic, hundreds of mineworkers suddenly appeared on their motorbikes, coming from all directions. You could feel the tension. As a white person, it’s better to keep your distance at a moment like that. A few weeks later I drove into a village to talk to the locals about their experiences with a nearby industrial mine. The mood was pretty tense. They presumably thought I was a representative of the mining company. When people became more and more irritated, I decided to abandon my plans and to drive on.

“Our research topic is politically highly charged – especially in the industrial mining sector – which means that people in a conflict situation can easily project their feelings onto us. So during my work I have to keep an eye on the bigger picture and understand the context I’m dealing with: what conflicts already exist, where do the fault lines run between the different parties, and what are the resultant risks for our work? It’s a major challenge to keep all that in mind all the time”. sj

Christelle Rigual - Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva | Image: Valérie Chételat

NIGERIA AND INDONESIA

“Scientists minimise their stressful experiences”

Christelle Rigual - Analysis of the role of gender in conflict and peacebuilding

“I’m a team member on a project analysing how gender influences and co-constitutes the processes of violence, conflict management and peacebuilding in several regions of Indonesia and Nigeria. Gender representations, and in particular social expectations related to masculinity, have a profound impact on individual, collective and institutional responses.

“There are many risks associated with this type of research. A colleague was involved in an armed carjacking in Nigeria, where her laptop was stolen and much of her research data was consequently lost. In Indonesia, members of an armed group demanded to be interviewed; the outcome of the confrontation was fortunately peaceful. Last year, the re-emergence of community violence in Plateau State in central Nigeria led to roadblocks and curfews, which meant we could not film a documentary on our research as planned. There are also dangers that cannot be anticipated. During a research trip to Indonesia in 2018, I had hoped for the chance to escape to the island of Lombok. What actually happened was an earthquake. I was lucky enough to get out unscathed, but I wondered if my research was really worth it. The answer remains yes.

“In my opinion, we need a platform where scientists facing risks in the field might seek information on how best to prepare themselves. As a gender expert, I see research remaining very much influenced by the male model of excellence. It leaves little room for expressing emotions or vulnerability. When scientists return from the field having lived through tense situations, they tend to play down their stressful experiences, or use irony as a means of coping. This feeds a vicious circle of isolation and absent institutional support for scientists”. pm