Feature: Getting creative against climate change

Karin Ingold: “The issue with Greta Thunberg is one of democratic legitimacy”

In the discussions about the climate crisis, we often hear doubts about whether democracies really have the right instruments for them to act effectively. Innovation is needed. The political scientist Karin Ingold explains why she, nevertheless, disagrees with suggestions such as parliamentary youth councils.

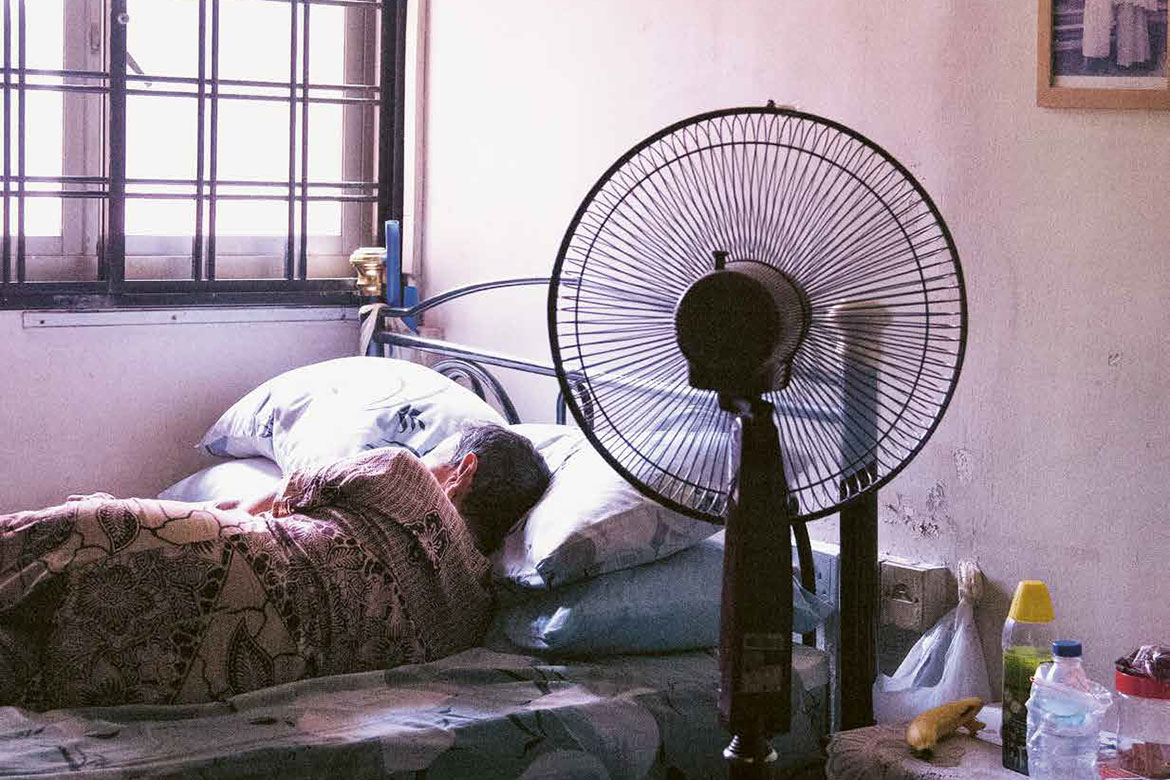

In the fight against the climate catastrophe, it can be tempting to resort to authoritarian means. But the political scientist Karin Ingold insists that preserving democracy must have priority. | Image: Ruben Hollinger

Karin Ingold, the biophysicist James Lovelock once said that humankind will only be able to overcome climate change if it treats it like a war. For that, democracy would have to be suspended.

In a consensual democracy, of which Switzerland is a prime example, decision-making can often take an incredibly long time. And such democracies generally only produce so-called soft policies, because compromises always respect the opinions of the many. Such processes usually do not result in innovative, spectacular solutions. But at the same time, it’s clear that democracies are especially well-suited to making peace. Broad-based, legitimate policies might not bring about short-term, large-scale change. But they ensure the long-term support of the population, which is at least as important.

Nevertheless, you too write that sustainability and democracy are not always compatible.

That’s true, because our decision-makers usually have a mandate for four years. After two years at the latest, they are no longer concerned with political issues, but about getting re-elected. Support for behavioural change – such as flying less and driving less – is not conducive to that. Their mandates could theoretically be extended, but then citizens would find they had been deprived of the freedom to deselect people who have made false promises.

Climate politics have found a new protagonist in the last two years: young people. They feel that their interests are not represented by the classical party system and are going onto the streets. What are their possibilities for participation within a democratic system?

There are innumerable arenas that can be activated outside the regular political machinery. As for the Fridays-for-future movement and Greta Thunberg, there are questions to be answered about their democratic legitimacy. No one has elected them to participate in politics. Why should Thunberg be allowed to speak before the UN and not someone else? Citizens have been unable to elect her, nor can they vote her out. It is difficult to discern the criteria that led to her being chosen to assist in political decision-making processes.

What about setting up parliamentary bodies in which the demands of young people and future generations are represented? The philosopher Bernward Gesang has proposed a third chamber comprising “future councils”.

I have a whole series of questions about that: Who are these representatives of future generations, and are they to be elected democratically? Are they supposed to be some kind of Nostradamus who can see into the future? We might well be able to calculate the resources that future generations will need to live. But what about their requirements and desires? Who can know today what they might look like? I think it’s more important for us to ensure that our descendants will enjoy the same democratic principles in the future that we do today.

What about scientists – aren’t they underrepresented in today’s political system?

If you’re suggesting that we should reserve seats in parliament for scientists, that’s something I could never agree to, because that would be a curtailment of democracy! Parliament has the task of representing a society’s values. As a citizen, I don’t want any voices in parliament that have not been legitimised democratically. I want to be able to vote its members in or out according to my own beliefs. I would also warn against any politicisation of science. There are other, more effective ways of bringing additional evidence into politics. For example, you could allocate greater resources for extra-parliamentary bodies incorporating scientists, who could then advise the government and parliament. Or you could invest more in political education and science communication.

In international climate negotiations, Switzerland is often perceived as being a pioneer. But here at home, political proposals to deal with the climate are proceeding only slowly. Why is there this discrepancy?

These are two completely different things. Climate delegations are relatively small and heterogeneous; NGOs and scientists are pretty strongly represented there. But if there is a national debate about CO2 emissions, then the Swiss Oil Association speaks up, along with the Swiss automobile association TCS, the homeowners’ association, and the consumer protection agencies. The degree to which different people are affected is crucial.

Shouldn’t the Federal Council be more energetic about trying to anchor international regulations in national legislation?

That’s not how things function, and I can give you a good example. After the environmental conference of 1992 in Rio, the then Swiss Minister for the Environment and former Federal Councillor Flavio Cotti came home and wanted to introduce a tax on CO2. Swiss businesses and certain parties were loudly indignant, complaining that he had not even begun the procedures for a legislative proposal. You see: Big, revolutionary ideas have a difficult time of it in Switzerland.

But the coronavirus crisis has proven that the Federal Council is able to take critical measures in order to protect the population. Shouldn’t they have similar powers with regard to the climate crisis?

These two crises are different for two important reasons: the manner in which people are affected, and the timescale. The Federal Council was able to implement its recent policy decisions partly because the population believes in orders that come from above, but also because people felt personally affected. That can help a policy to be successful. With the climate crisis, too few people are directly affected. The same applies to the timescale: the climate crisis is a long-term thing, and the truly awful impact of it is only expected to become manifest in a few years or decades. Many of our decision-makers today are over 60 or 70, so they are not going to be affected much. In the case of COVID 19, however, the crisis is immediate and acute.

So if there isn’t an acute crisis, revolutionary ideas have a difficult time of it in Switzerland. What political and democratic possibilities are there that might nevertheless enable us to combat the climate crisis in a more efficient manner?

Our system does offer open doors for innovation. In many fields, there already exists a close collaboration between scientists and politicians. If together they were able to propose new climate measures that could gain a majority in parliament, I could see a lot of potential for setting up effective instruments. But the authorities and the business sector also are in close contact with each other. If businesses start participating actively in shaping climate policies, then thoroughly innovative ideas might be realised. And last but not least, the instruments of direct democracy mean that political innovations can also be proposed by the people.