Visual society

The power of images

Today, we communicate so often using photos and other visual media that some people have begun complaining of a loss of complexity. And yet images can help us to focus on people and connections previously considered insignificant. This is especially true in art.

Logos, selfies with friends, ads and snippets from Google Maps: In his installation ‘Since you were born’, Evan Roth presents all the images that flooded his computer screen in the four months after the birth of his daughter. | Image: Evan Roth.

There are images that have gone all round the world. The photo of our blue planet from the moon, made by the Apollo 8 crew in 1968, shifted our perception of what is near and far. The mushroom cloud over Hiroshima remains a monument to the horrors of atomic war in our collective memory. Photos of the Graf Zeppelin airship hovering on its maiden flight over Friedrichshafen in 1928 also show the astonishment of contemporary bystanders. Such visual testimony to historical moments is typical of a time when not every middle-class household possessed a camera of its own; these images were a result of progress both technological and military. Since cameras began to be included with every new mobile phone, we have had access to digital platforms that not only allow us to communicate our personal opinions constantly, but have brought into our everyday consciousness a world of innumerable images of manifold origin. Any term we enter in a search engine brings forth a kaleidoscope of visual information, and the latest telecommunication applications present us with new images every day.

The Earth rising behind the Moon. This picture, taken by the Apollo 8 crew, showed the inhabitants of the Blue Planet just how fragile their home is. | Image: Nasa

Real dangers – endangered images

The lockdown in spring 2020 also made us ponder what it means when we increasingly use just images to engage in dialogue with each other, whether on social media platforms or on messenger apps. “An image we share is answered with another shared image, and often there is no text involved at all. Some might complain that this signifies a loss of civilisational complexity, but perhaps we first have to take a serious look at what it means to engage in dialogue using images”. Emmanuel Alloa, a professor of aesthetics and philosophy at the University of Fribourg, is adamant that images are purveyors of knowledge that cannot be regarded as subordinate to language, nor as attributes of it, not even in the sciences. “Meaning can also circulate through very different channels, and there is also a form of graphic reason besides the logocentric reason we already know”.

The past few months have proven that “what we know about the world is increasingly entering our living rooms through images”. What’s more: “We react and intervene in the world using pictures too”, says Alloa. In our everyday lives, we treat this as something utterly natural. “Our global access to visible reality is technological and occurs through visual media – and yet we still have a poor understanding of how extreme proximity can switch to extreme distance”. During the bombing of the Gaza Strip in 2015, the mother of the Palestinian artist Taysir Batniji was stuck there, and so he tried to remain in contact with her using Skype and WhatsApp. His screenshots show how closely interlocked are politics and personal experience: His image of his mother was “endangered” by an unstable transfer of data that repeatedly dissolved her face and upper body into coarse pixels.

Prostheses for perception

Batniji’s series of works, entitled ‘Disruptions’, offers proof of the ordeal that this new form of distance vision places before us. It was exhibited in ‘Le supermarché des images’ (Supermarket of images), a large-scale exhibition in the Galerie nationale of the Jeu de Paume in Paris in spring 2020, although the Covid-19 pandemic meant it had to go virtual just a few weeks after opening. Alloa was the co-curator, and brought to the exhibition his knowledge of the complex interactions that exist between image, consumption and mobility.

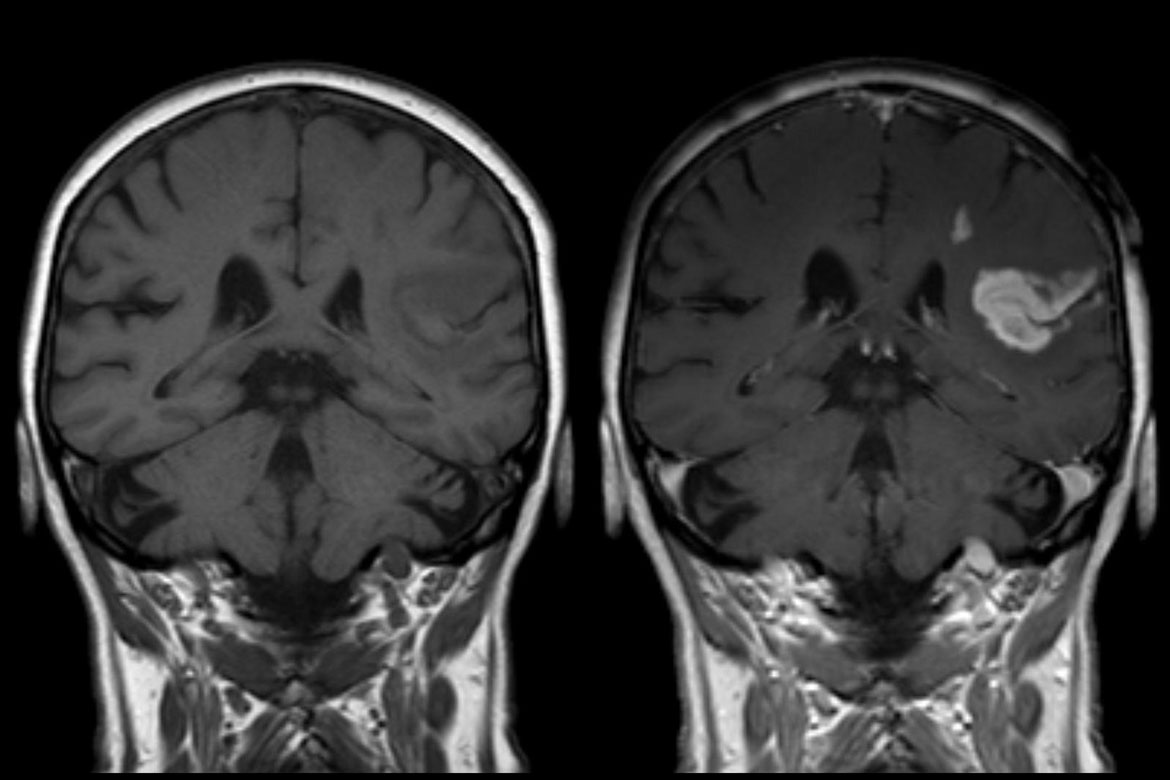

“The visualising power of images means they must be counted among the most significant cultural techniques”, says Alloa. “The exhibition endeavoured to visualise the processes of a globalised economy, and referred back to a long history of imaging techniques in the natural sciences”. Hand-made drawings of pharmaceutical plants, telescopes to observe the heavens, and X-rays in medical diagnostics together signify just a few stages in the history of image-based knowledge. “But it would be wrong to see images only as prostheses, as extensions of our natural powers of perception. Many images pose a direct challenge to our perception, and ask questions about our ethical framework. This always happens when they confront us with perspectives that do not suit our ideology”. Or when they make us pay attention to the dark underbelly of our interlinked world that we otherwise insist on ignoring.

Some things remain overlooked

Alloa remains wholly aloof from the cultural pessimism that images often evoke, and he avoids any claims of oversaturation, or simple categories such as ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Instead, he believes that his scholarly engagement with images means assessing what realities still remain unrepresented, despite the omnipresence of images today. “In the high-speed circulation of our thermo-industrial late Modernism, many things flicker into view but briefly, and so remain overlooked. It is precisely such things that need an advocate – things that do not have a voice of their own to demand attention”. It also means taking a closer look at the interests hidden behind this flood of images.

“We assume that the media are transparent channels through which everything flows unhindered and uninfluenced”, he says. But this is a misunderstanding. “The realm of images is no power-free space, because it too is subject both to a compulsion to standardise, and to mechanisms of exclusion. This is clearly revealed in the works we exhibited by the feminist American artist Martha Rosler. There are pictures that confirm or enhance stereotypes, or that engage observers to such an intense degree that they are unable to engage in any critical debate”. Advertising is able to employ such strategies cleverly, by using ‘beautiful’ models and their accessories to conjure up notions of happiness, health and prosperity, and then shipping these ideals of beauty around the whole world.

Alloa’s research repeatedly refers to works from the fine arts. This is not surprising. Art is independent of functional necessity and is open in its results, so it can leave or transform common-or-garden perspectives, thematise the effective power of images, or ask critical questions of them. “The history of art is a continual experiment in prompting observers to learn new ways of approaching and comprehending things, not just accepting them as given. This already begins when a picture brings people, collectives or relationships into focus that up to then had been regarded as insignificant or neglectable”. The video and photo artist Lauren Huret does just this in the ‘Supermarket of images’, where she shows female IT workers in Manila who spend all day watching online images in order to censor those that are offensive – this despite our common belief that impersonal algorithms do all this work for us. Huret suggests that they are latter-day successors to Saint Lucia, who according to legend sacrificed her eyes in order to evade a suitor. The world pays a heavy price for wanting to make everything visible to everyone, while in fact exploiting the vulnerable to correct its mistakes.

Visiting Assange

Computer networks were still relatively young when the Swiss media artists Carmen Weisskopf and Domagoj Smoljo came together in 2000 to form the media duo called !Bitnik. Since then, they have focused their work on power relationships and on the lack of transparency in networks that feed off the data of private individuals. “Images have assumed a new dimension, in that once they are uploaded, they can in some way be utilised as data input by the military industrial complex”, says Weisskopf. “All neural networks are trained to be used by intelligent machines that are ultimately designed for surveillance purposes”. !Bitnik does not simply accept this as given, but has adopted their surveillance principle as its own.

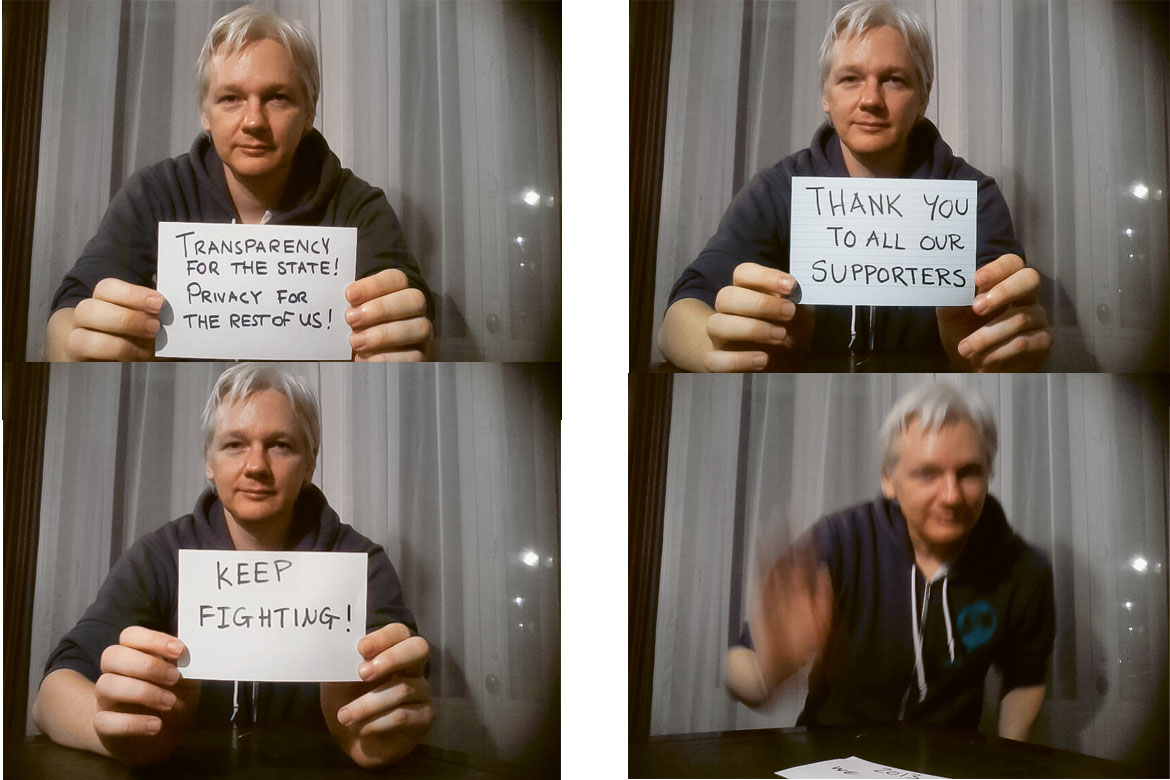

A camera in a package sent by mail filmed its 32-hour journey to the Ecuadorian Embassy in London. Thousands of people followed its progress on Twitter. At the end of this experiment, Julian Assange used it to photograph himself. | Images: !Mediengruppe Bitnik

Several thousand people looked on when a camera reached Julian Assange by mail in January 2013. Through a peephole in the packaging, a GPS transmitter sent images of its transport route in real time, all the way to the Ecuadorian Embassy in London. A website and the duo’s Twitter account became the interface for this transmitter, which travelled unhindered along conveyor belts, through depots and inside a delivery van. After a 32-hour live stream, the Wikileaks founder thanked them by sending a selfie to them on 17 January. “Postal Art is Contagious!” was written on the note that he held up to the camera. “Even if our package did not power its own way, our action nevertheless turned that package into an actor”, says !Bitnik. This project, “Delivery for Mr. Assange”, was regarded as a live performance by !Bitnik, even though the artists did not have any physical contact with their ‘audience’. Their work was a reflection on just how intensively networked data can upend the conventional relationships between body and image.

Ultimately, images have long assumed control over our collective actions. The rising curve of Covid-19 infection rates keeps us distant from each other, and is altering our shopping habits; and measuring processes – such as sleep and motion apps – are being used for healthcare provision. Such visual information is redrawing the boundaries between the public and the private. There is no such thing as ‘mere images’ any more.