Provenance

A globetrotting screen

Made in Japan, bought in China, altered in Europe – the biography of a well-travelled dividing screen, a ‘paravent’, can tell us much about Switzerland in the 18th and 19th centuries.

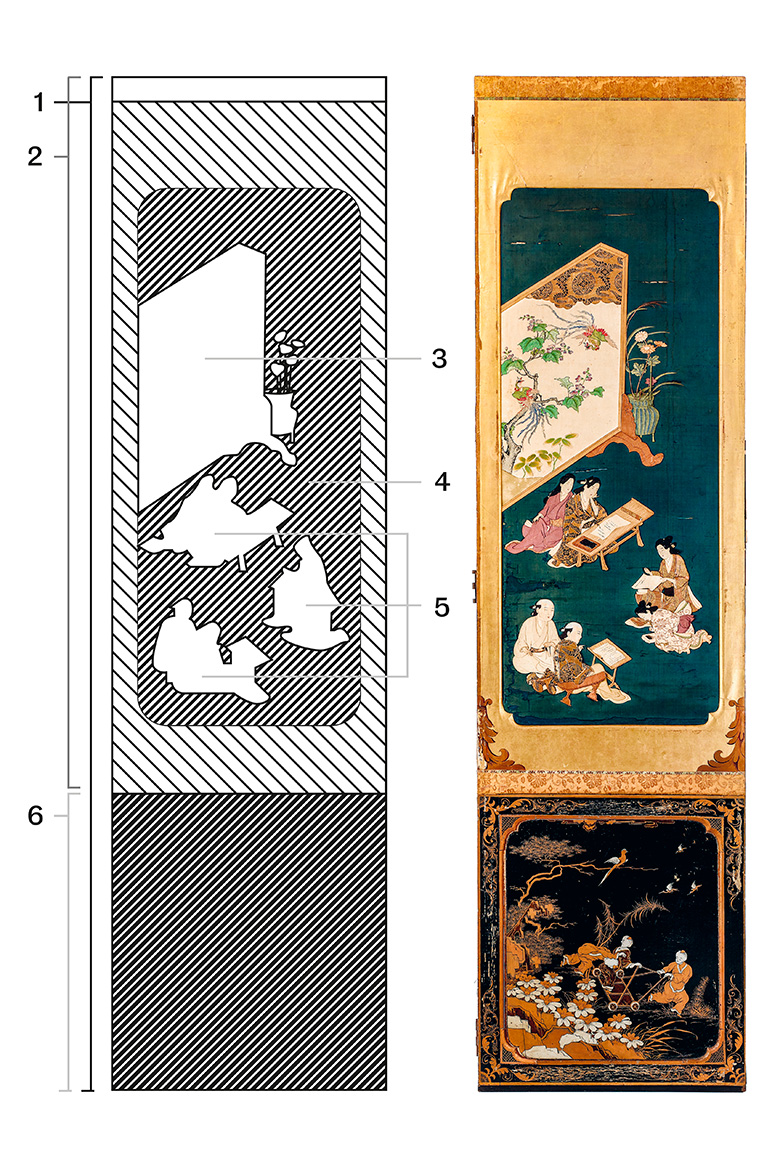

This panel from the 18th and 19th centuries was restored by the Musée Historique de Lausanne for the exhibition ‘Exotic?’ under the direction of the conservator Claude-Alain Künzi. | Photo: Musée historique de Lausanne

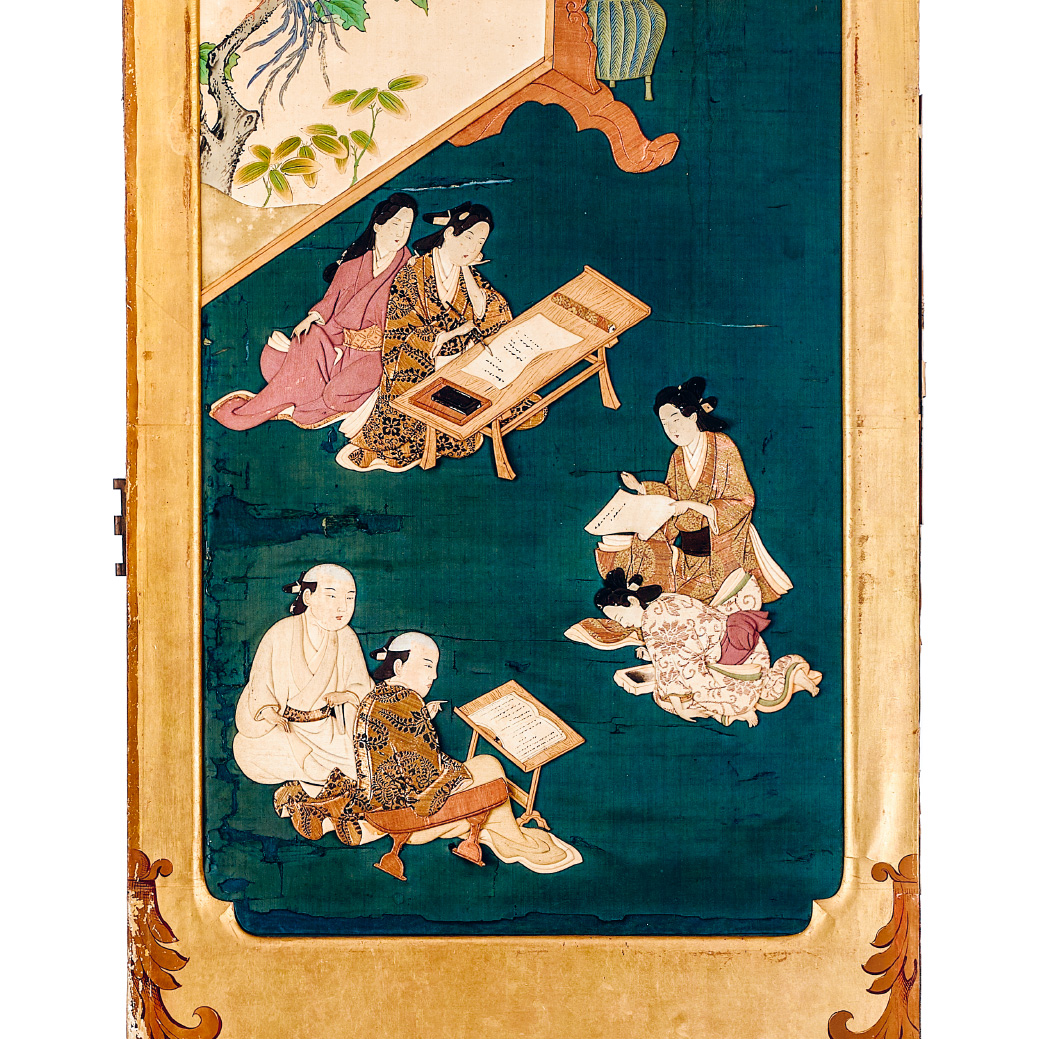

Prosperous merchants at leisure, reading, and noble courtesans penning a poem: the Japanese scene on the blue-and-gold upper portion of this panel awakens notions of a culture both intensely sensual and intellectual, sublime and delicate. The European bourgeoisie of the 18th and 19th centuries was especially enthusiastic about Japan and China, because large parts of these exotic countries had not merely managed to evade the imperial ambitions of the great powers of Europe, but were also largely closed to visitors from the West. The handicrafts of the Far East were also of financial interest: merchants sensed an opportunity for doing big business with the techniques, styles and motifs of these unknown artists. Imitations were avidly made, though they mostly fell flat when in direct competition with the original artworks from South-East Asia. One example of such an imitation is the lower, black section of this panel.

This hybrid paravent demonstrates the intercontinental network that already existed in Europe at the time of the Enlightenment. But the state of this screen reflects how it has suffered over the centuries. The researchers hope that its other panels might be restored after the exhibition in Lausanne, which lasts until late February 2021. Besides its artful scenes from Japan and Europe, this well-travelled object also bears within it many a hidden story from the 18th and 19th centuries: the padding material inside the panels comprises written documents and letters. “Paper was valuable back then”, explains Lee, “so it wasn’t just thrown away”.

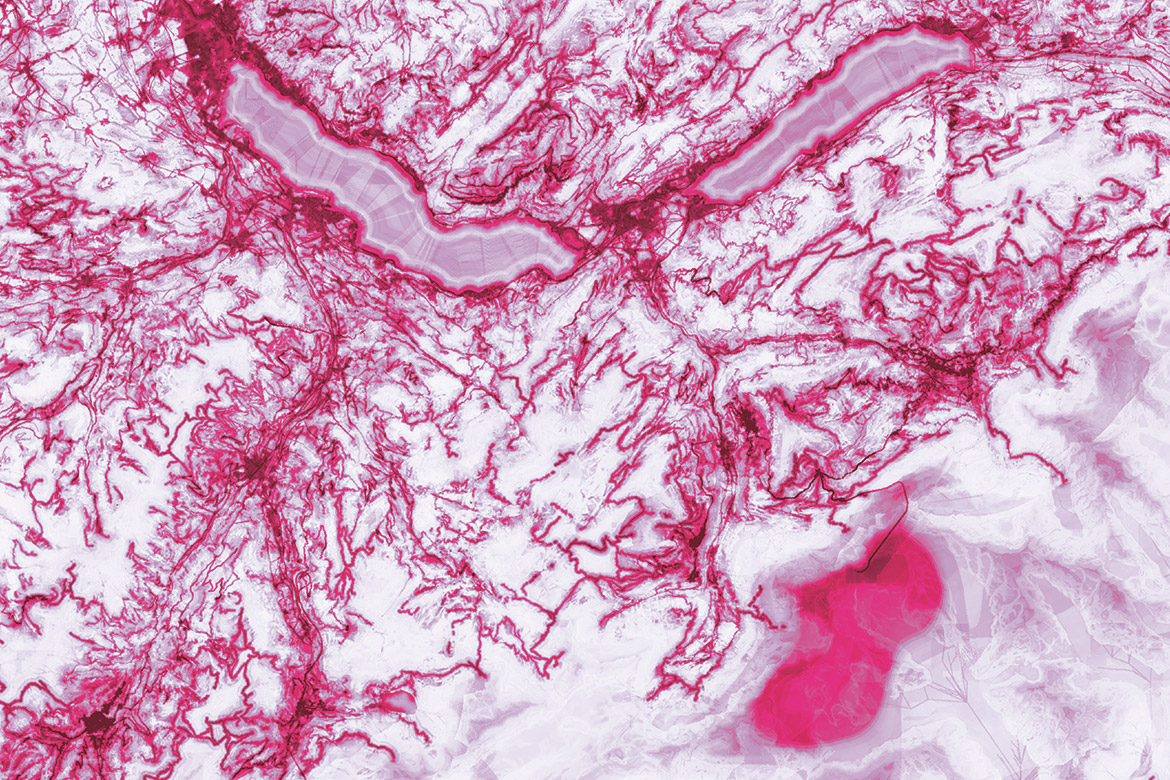

The exhibition ‘Exotic?’ only shows foreign objects that were already in Switzerland before the Congress of Vienna of 1815. In order to track down these objects, the researchers Étienne, Lee and Claire Brizon – all of them from the University of Bern – trawled through museum depots throughout Switzerland. Constant De Rebecque returned from China in 1793, and we know that no one else from his family went there; what’s more, he mentions this paravent in a letter to his sister. So it fulfils the criteria for the exhibition. “Examples such as this show how objects too can have a biography: they travel, are changed, and in the process alter the material culture of Switzerland”, says Brizon.