Feature: Diversity in the academy

Women students, but no women’s toilets

Women were admitted to Swiss universities at a relatively early date. But this doesn’t mean that ‘diversity’ was a popular concept in tertiary education at the time.

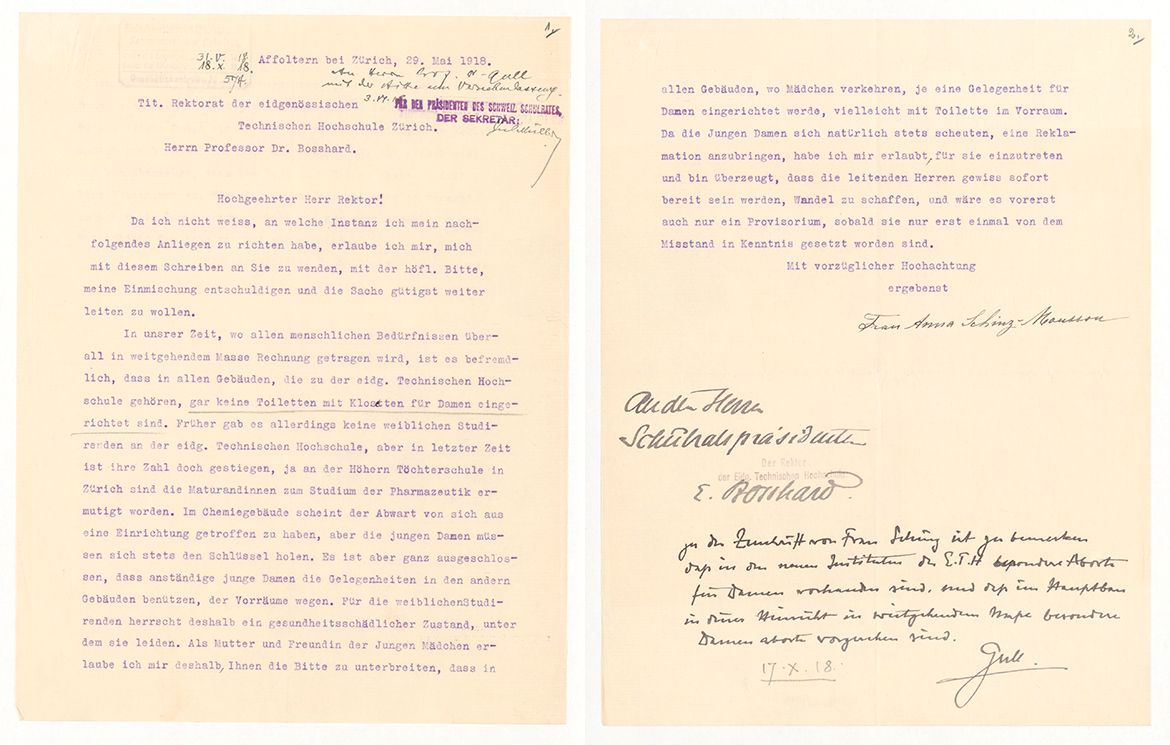

“A state of affairs exists that is thus damaging to the health of women students, and they are suffering under it”, wrote Anna Schinz-Mousson to the Rectorate of ETH Zurich on 29 May 1918, complaining of a lack of women’s toilets. Letter in the historical archives of the ETH Board (ETH Library, Archive, SR3 1918, No. 574)

In 1918, a letter of complaint arrived at the President’s office at ETH Zurich. Its author, Anna Schinz-Mousson, wrote of how “bewildering” it was that there were no women’s toilets in the main building of the university. Schinz-Mousson belonged to one of the most influential Zurich families, and it was simply beyond the pale to her that “decent young ladies” studying at ETH should have to use the men’s toilets.

Women students ridiculed

It might seem astonishing that no women’s toilets existed at ETH until well into the 20th century – after all, Zurich was one of the pioneers in Europe when it came to admitting women to university. Whereas universities in other countries were peopled by the male members of their respective upper classes, women had been able to matriculate as regular students in Switzerland since the second half of the 19th century. At the same time, however, this toilet episode shows that the Swiss university landscape only got used to the idea of equality of the sexes very slowly. It was less progressive that one might surmise, despite the early admittance of women to their study programmes.

These early women students in Switzerland also generated much scepticism. “Women students were ridiculed or ostracised by both their fellow students and the general population” says Regina Wecker, a retired professor of history at the University of Basel. This is confirmed by a polemical pamphlet written by a professor, who in 1872 went so far as to write in the newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung that women lacked the “intellectual capacity” to study medicine. As evidence, he referred to the difference in weight between male and female brains.

In the early years, most of the women students at Swiss universities were from Russia. They were thus different from the majority of students not just in their gender, but also in their nationality. The general extant hostility to women students was thus compounded by xenophobia. These “Russian wenches”, as they were called, were also accused of venturing to “the outermost boundaries of morality” with their supposedly lewd behaviour in pubs, a purported predilection for free love and a penchant for political activity.

“The higher the status, the fewer women there are”

It took over a hundred years for women students to cease being considered exotic at Swiss universities. “While women were allowed to study early on, this did not result in any kind of continuous process, neither with regard to the numbers of women students nor with regard to the emergence of women professors”, says Wecker. But when their numbers increased at Swiss universities towards the end of the 20th century, it was finally acknowledged that a more diverse university environment offered potential for success – such as the increase in creativity that was observed when research teams comprised both genders. In tandem with this, equal opportunity offices were set up at many universities, and these gave a further boost to the idea of diversity.

Nevertheless, it took a long time for the presence of women to become the new normal on the Swiss university landscape, and this has had an impact to this day, as is confirmed by the gender researcher Patricia Purtschert of the University of Bern: “We can still observe the pyramid effect everywhere: the higher the status, the fewer women there are”. She also emphasises that there are other topics coming into focus when we talk of diversity, above and beyond the equality of the sexes. These include structural racism, the privileges enjoyed by students from the middle and upper classes of society, and the barriers that exist to people with disabilities.

This expansion of ‘diversity’ is again being reflected in the issue of toilets. Some hundred years after the abovementioned letter of complaint was taken to heart by ETH Zurich – it resulted in women’s toilets being installed in the mezzanine floors – the same institution, along with other universities, has seen itself subjected to similar criticism once again. Roughly a year ago, it was the lack of gender-neutral toilets in the older and smaller buildings of ETH Zurich that caused a stir. Then there was a debate about WC signs at the University of Lucerne, where a toilet had been designated for transgender people and for the disabled, implicitly equating the one with the other. Both Lucerne and ETH accepted the criticism, and adapted their toilets accordingly.