POLITICAL CONSULTING

No trust without self-criticism

In recent months, trust in science first increased, then decreased. We look at what needs to happen if the general population is truly going to reap the benefits of research.

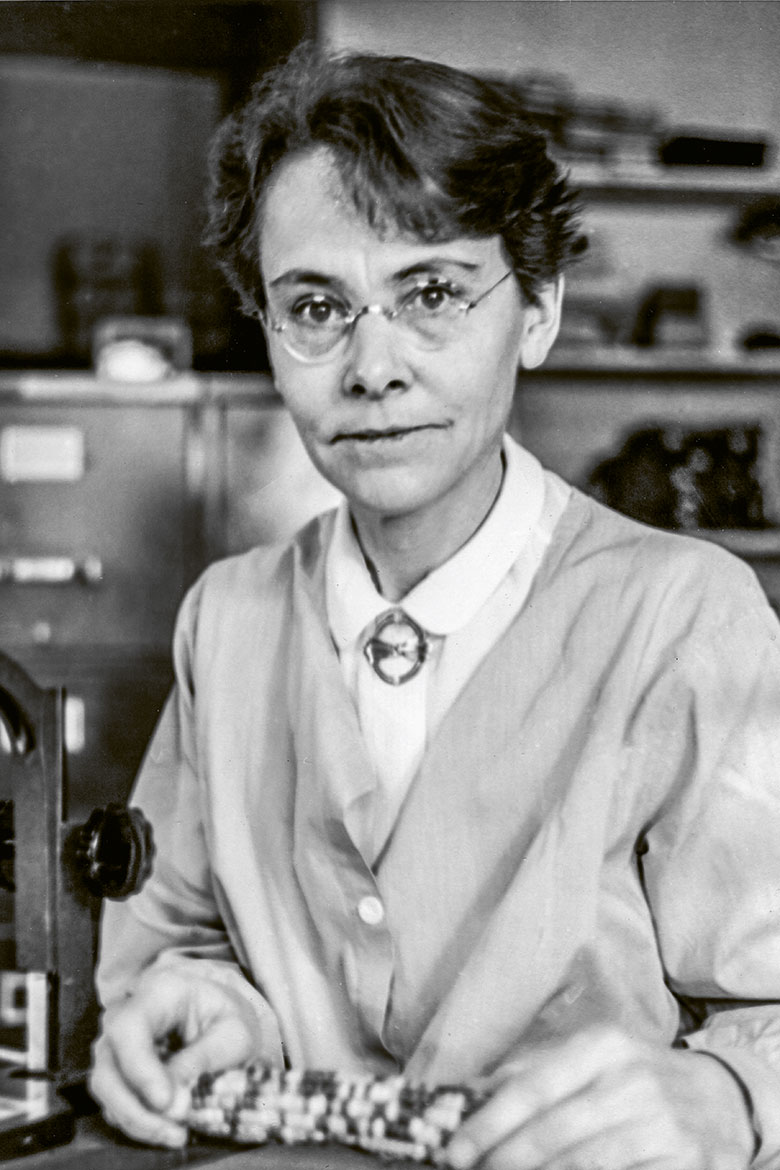

The COVID-19 Task Force provided an important point of reference for the Swiss population. The fact that it was repeatedly subjected to criticism (and continues to be criticised) is in fact a good sign. | Photo: Peter Schneider/Keystone

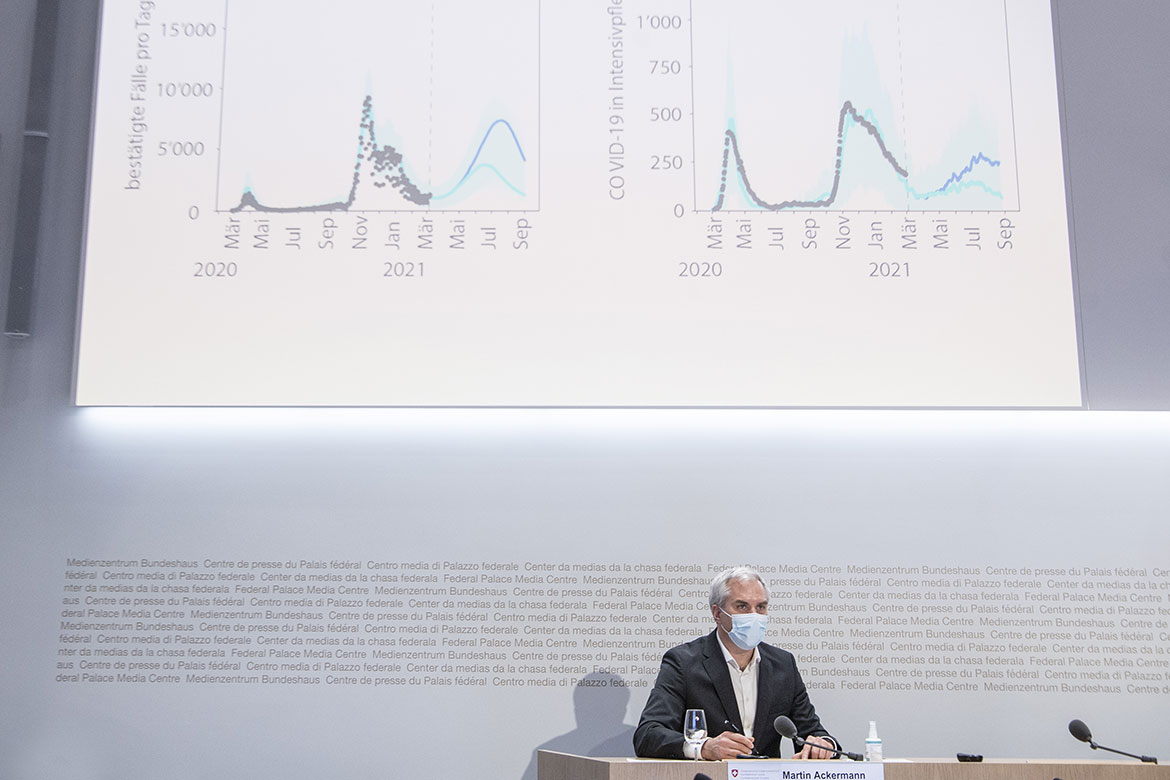

In the current pandemic, the population has not had much choice except to believe the experts of the country’s research departments. Initially, they did just that, as we can see from the ‘science barometer’ set up by researchers at the University of Zurich in the spring of 2020. During the first wave of the virus, trust in science rose by 0.2 points to 3.8 on a scale of 1 to 5, when compared with surveys conducted in 2016 and 2019.

Psychologists and political scientists call this effect ‘rallying round the flag’. In times of crisis, many people rely on those whom they regard as trustworthy, established figures of authority. What is decisive is whether people can believe in their expertise, whether that expertise is communicated in a way that seems authentic und truthful, and whether these experts truly seem to have the wellbeing of everyone at heart. At the beginning of the pandemic, everything looked good for science.

But with the second wave, criticism of scientists became more strident – at demonstrations on the streets, in articles in the media, and among politicians. In February 2021, the Swiss parliament’s Economic Commission argued in favour of banning members of the Swiss National COVID-19 Science Task Force from speaking in public. The honeymoon period is definitely over.

In fact, we can see a retreat from ‘rallying around the flag’ in many countries, says Mike Schäfer, a professor of science communication and co-head of the team responsible for the science barometer. In Germany, for example, the barometer measured a major increase in how many people trusted science at the beginning of the pandemic – from a long-term average of roughly 50 percent to no less than 81 percent. That was in April 2020. One month later, however, it was down to 73 percent. “But in relative terms, it is worse for the media and politicians (such as those in federal positions). In those two cases, we can already see a major drop in trustworthiness”, says Schäfer.

Criticism is a quality criterion

Schäfer sees the reasons for this in how researchers have engaged in uncoordinated criticism of politicians and the authorities. Christoph Zenger is a professor of health law who has analysed the Epidemics Act of 2018, and in an interview for the Aargauer Zeitung, he noted that that “many people are now so confused that they say: ‘I’ll just do what I want’”. Criticism of the Task Force also became ever louder on online media. Sometimes, differences of opinion among members of the Task Force were also aired in public.

The problem is that providing critical commentary is one of the core functions of science and scholarship. Mutual criticism is in fact regarded as the prime quality criterion in science. “There is no singular scientific method. There are many scientific methods. What makes scientific claims reliable is the process by which they are vetted”, said the science historian Naomi Oreskes in an interview: “All scientific claims are subject to tough scrutiny, and it’s only the claims that pass this scrutiny that we can say constitute scientific knowledge”. This procedure is known as ‘organised scepticism’.

Because discussions are suddenly being conducted in public, everyone is now able to see that scepticism is not a matter of self-serving justification on the part of researchers. Caspar Hirschi for one is delighted that debates about new studies have moved into the public sphere, out of the anonymised peer-review process used by specialist journals. He is a historian at the University of St. Gallen and the author of a book about scandals surrounding experts. The problem at present, he says, is that people are arguing less about scientific findings and more about how these can be translated into concrete guidelines for action. “When the media and researchers blur the boundary where science ends and politics begins, they are themselves contributing to an atmosphere of mistrust in a form of research that comes across as expertocracy”.

Respect doesn’t mean blind trust

Oreskes and Hirschi both believe that the population can and should rely on science as long as scientific debate among researchers functions properly. Emanuela Ceva, a philosopher at the University of Geneva, is of a different opinion. She believes that trust arises in the relationship between two parties and depends on their reacting to each other in an atmosphere of mutual respect.

Ceva is investigating why representatives of institutions regard themselves as reliable partners (or not) – such as the members of the Task Force and employees of the Federal Office of Public Health.

“The two parties in a relationship have to treat each other mutually as responsible people”. Nor is it just a matter of being friendly and polite. “Respect needs a critical attitude towards the content of the information we receive, not just blind trust”. In other words: the authorities may not use scientific knowledge merely to find reasons to justify decisions they’ve already made. Nor may researchers expect politicians to implement their findings exactly as they might want.

The same applies to dealing with the general public. It is an imperative in social ethics that people should be treated as responsible citizens who are capable of making responsible decisions themselves. Only then will they be prepared to adapt. “People want to engage critically. If decisions are simply made and pushed through, then people feel as if they’re being treated like children”.

But the pandemic is a challenge that has never existed before, and it has developed in a highly dynamic manner. This applies especially in the liberal democracies of Europe that like to uphold fundamental freedoms, as demonstrated by a study conducted in April 2021 by the Centre for Democracy Aarau. The more democratic a nation is, the fewer the limitations implemented during the pandemic – irrespective of the epidemiological situation.

Can journalism fix it?

The task is all the more difficult for those whose role is mediating between researchers and the rest of society. “Science communication and politics have to support each other. Twitter is simply too superficial for this”, says Ceva. Hirschi also believes that science journalists are in a position of great responsibility: “Their role is to subject big-name scientists to critique, but in the pandemic, it’s sad to say, they have pretty much held back”. He believes that it ought to be their job to delineate areas of dispute and to point out the possible implications of different facts. “Regrettably, the media have often been more concerned with who’s right and who’s wrong, instead of identifying the real issues”.

This is also the opinion of Sara Rubinelli, a philosopher and professor of health communication at the University of Lucerne. She believes that the process ought to be the prime consideration. Then the difference can become apparent between scientific evidence and mere opinions. It has to become clear how researchers deal with new topics, and this also means always stating what they know and what they don’t know. To this end, researchers have to enter the public arena: “, says Rubinelli. This critical engagement with one’s own research can in turn help the general population to make well-informed decisions.