Portrait

The insatiable curiosity of Raffaele Peduzzi

Nature, mountains and the countless organisms inhabiting them have always fascinated Raffaele Peduzzi, a professor of biological sciences. It’s why he has spent his life passionately studying them. Even in retirement, he is still taking on new challenges.

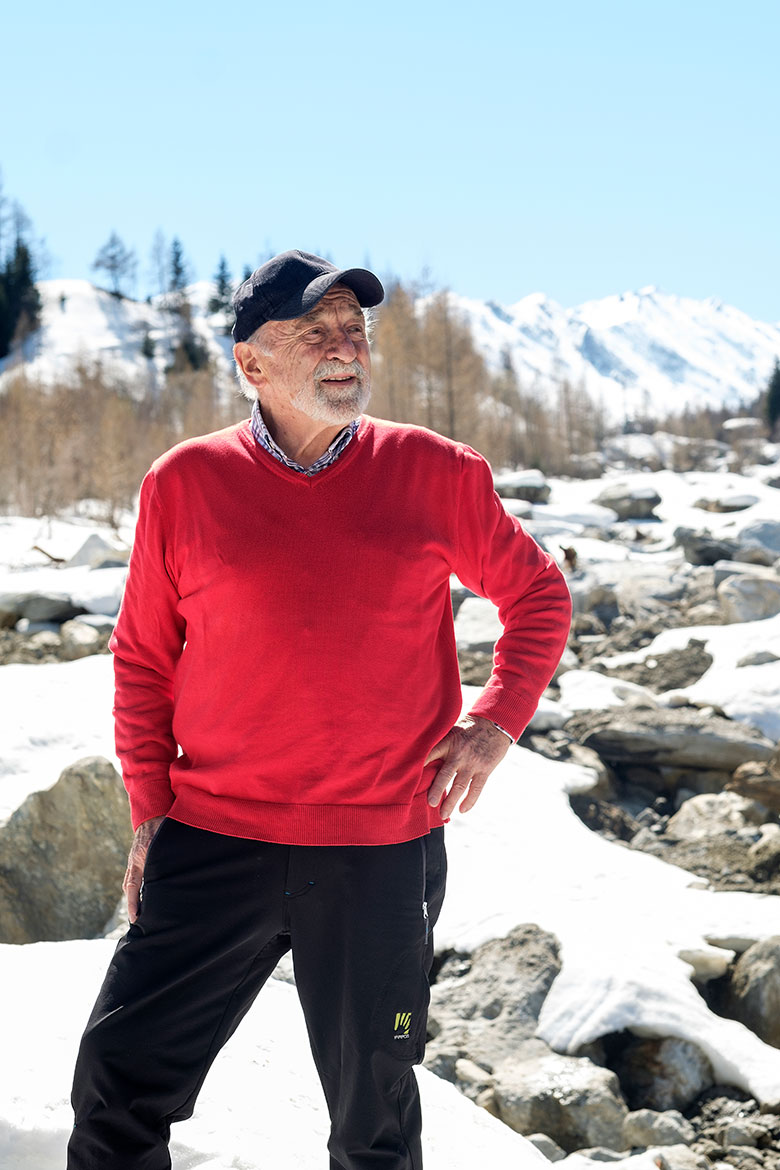

Raffaele Peduzzi has already made big changes in Val Piora, and he has further plans for the future: the creation of a House of Sustainability. | Image: Claudio Bader

Vast, majestic and enchanting, Val Piora boasts an incredibly rich variety of natural features, including a constellation of alpine lakes. It is one of the most pristine landscapes in the Swiss canton of Ticino, a plateau that lies between the districts of Leventina and Blenio at some 2,000 metres above sea level.

Raffaele Peduzzi was born here. Today, 79 years later, this Swiss-Italian biologist still can’t resist the magnetic pull of this unique, diverse environment. This valley is inextricably linked to his career, keeping him busy on several fronts, and rewarding him with its rich geology, flora and fauna.

As a little boy, he didn’t want to be a train driver or an astronaut: instead, he dreamt of a life immersed in Nature, in the world of plants and animals. “Up in Piora, there are ibexes and chamois, mammals that I admire for their ability to adapt and move across difficult, inhospitable terrain. But there are also rare examples of white marmots, alpine hares, spotted nutcrackers, bluethroats and even alpine salamanders! And there are surprising species of plant, like the glacier buttercup, which can survive even the coldest temperatures thanks to glycerol, a sort of antifreeze. There is a whole universe to explore up there!”

This is a passion that he has combined over the years with teaching and sharing his knowledge.

The young Peduzzi trained as a teacher, like many other Swiss Italians at the time. He first taught at his local school in Madrano, a tiny hamlet on the road leading to Val Piora. But the school environment couldn’t satisfy his thirst for knowledge or his fascination with Nature’s mysteries, so he enrolled at the University of Geneva.

Out in the field rather than in the lab

There, Peduzzi would spend decades studying the subjects closest to his heart: hydromicrobiology, bacteriology, virology, limnology and, above all, alpine biology. After graduating, Peduzzi worked as an assistant at the university’s microbiology laboratory while studying for his PhD. Once he obtained his doctorate, he was appointed to teach practical microbiology in 1970. Peduzzi’s career took off, and he found himself teaching further afield in Switzerland – at the universities of Neuchâtel and Lugano (USI), and at EPFL and ETH Zurich – as well as abroad, including in Paris, Milan and Varese (Insubria). He also worked for eight years at the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (Eawag), at both its Zurich and Kastanienbaum offices, where he spent most of his time conducting research into aquatic bacteriology, mycology and lake biopathology. Between 1989 and 2007, Peduzzi was the president of the Swiss National Science Foundation’s Commission for Italian-speaking Switzerland.

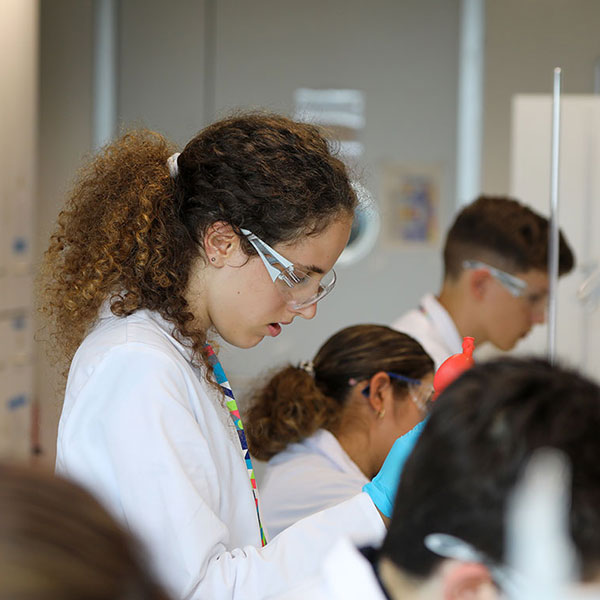

But while he had a deep passion for science, Peduzzi found the indoor environment of lecture halls and laboratories restrictive. Embracing Rousseau’s motto of “sortez, marchez, sentez, herborisez!”, he began to give a series of practical classes out in the field, with Val Piora one of his favourite destinations. At first, students would collect rock and water samples, and take them back to university laboratories to study. “It didn’t make much sense. Nature should be studied in the field, its elements observed and analysed in their original habitat. A hit-and-run approach should be avoided”, insists Peduzzi, who at the end of the 1980s channelled his energies into a new project: building the Alpine Biology Centre in Piora, which was modelled on France’s marine research and teaching centres in Roscoff and Banyuls-sur-Mer. These are not just places for research, but for sharing knowledge and mutual understanding, because it’s from such synergies that the best ideas are born.

In 1989, the canton of Ticino appointed Peduzzi as the head of this project. Five years later, thanks to collaboration and funding from the universities of Geneva and Zurich, the canton of Ticino and the Federal Department of Home Affairs, the Centre opened its doors in Val Piora. Housed in two carefully restored 16th-century farm buildings known as “barc”, it comprises three laboratories, a classroom, two dining halls, a library/archive and dormitories sleeping 65 in total. And so a new world opened up to academics and students, a place where they could explore a natural habitat rich in biodiversity – home to some 1,732 species of plant and 780 species of animal – while tasting the Alpine way of life, with its platters of Piora cheese, venison salami and glasses of good wine. It’s a world that has exerted a strong pull on Peduzzi’s students over the years, so much so that over the course of his career he supervised some 30 PhD students: “I’ve supervised lots of them and our relationship has always been great. It was helped by being able to get to know one another on field trips, at a sort of extramural university”.

At the same time, starting in the 1980s, Peduzzi also served as the director of Ticino’s Cantonal Institute of Microbiology for 30 years. He has helped to create a number of educational trails, including the microbiology trail around Lake Ritom. Together with his son Sandro, he has also created an itinerary for the Hydrological Atlas of Switzerland. Indeed, he believes that the popularisation of scientific concepts among the general public is essential because, as he emphasises by paraphrasing the French philosopher and biologist Jean Rostand, “the world will be a better place when people are more biologically mature”.

Cultured and enlightened, Peduzzi firmly believes that teaching people to respect Nature is fundamental for the future of our planet: “In Piora, for example, we need to keep doing research to find a balance between different needs: the needs of Nature, the needs of livestock farming and the needs of hydroelectric power”. The issue of the environment – which is such a pressing question today – was already being talked about by scientists in the seventies, recalls Peduzzi, citing ‘Before Nature Dies’ by the French ornithologist Jean Dorst. In 1965, he said, “in Europe, the only unpolluted areas left are in the mountains”. Now, the situation has further deteriorated and the first effects are there for all to see. “I’m very worried: the effects of climate change are even clearer to see at high altitude”, he concludes.