Feature: In virtual space

“A virtual space is like a bubble extending into another dimension”

We log on, upload and download. Our language has long shown us that electronic services are also places. Tobias Holischka, a philosopher of technology, has been defining these virtual spaces.

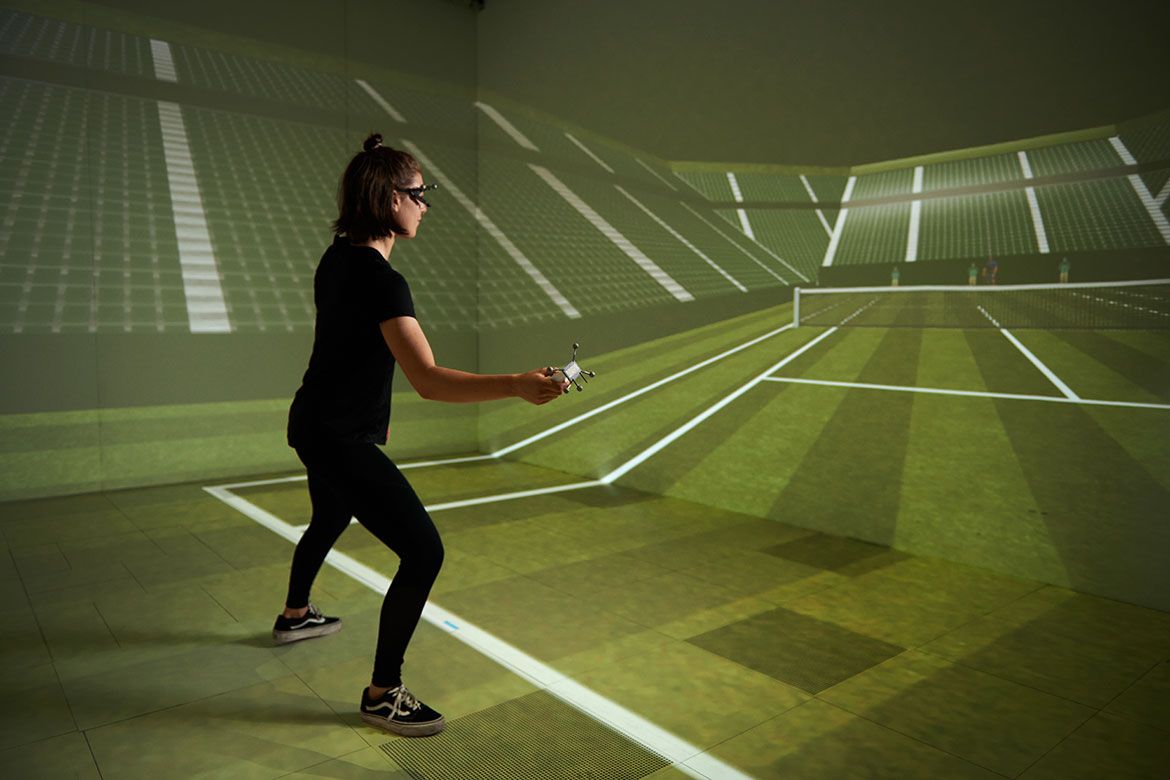

Virtual doesn’t mean something isn’t real. The philosopher Tobias Holischka takes a relaxed approach to new technological possibilities. | Image: Sebastian Arlt

Tobias Holischka, we’re meeting virtually, aren’t we?

I’d call it virtual, because that’s how the word is used at present. It’s not virtuality in the true sense of the word. We only mean that we’re not meeting physically. But this perspective presents a problem. Virtuality is here set up in opposition to reality. Yet no one would question the fact that we are both now having a real meeting, despite doing so online. You are not an illusion, and I’m not a computer game to you. I’m on my guard about this because the concept of ‘virtuality’ is constantly shunting everything into the realm of the unreal.

Why is that a problem?

For many researchers in the humanities, the concept of virtuality is a trigger that makes them ask: what does it mean if we are only meeting virtually, not in reality? If we use it like that, then the word is a red herring. The same applies to other concepts such as artificial intelligence. Whoever doesn’t understand the technological background might think: for goodness’ sake, now we have artificial intelligence, and we used to have just natural intelligence! But it’s only a name for a type of technology.

I understand. We are talking today primarily about virtual spaces. Let’s say we’ve been meeting for the past year in new places. Do we need a new approach to spaces?

Yes. If we are going to keep using the old conceptual toolbox, then what we see on our screens, whether it’s an e-book or a social network, is only a two-dimensional wall of text. At first glance, everything seems to be the same. But we are dealing with completely different phenomena. When we use e‑banking, we’re situated in a completely secure area that is password-protected. On a social network, by contrast, I’m sending personal messages. Our vocabulary has long been showing us that these are places. We log on, we download things. This lets us see a dimension that used to be hidden. In this sense, they really are virtual spaces. Because originally, a space was a place where things were juxtaposed. Virtual spaces, however, are not part of material space. There isn’t a road I could drive along to reach my electronic mailbox. It’s more like a bubble that extends into another dimension.

Humanity has long been expanding its realms in a physical sense. We’ve discovered new continents, gone into space. Now we are expanding into inner spaces, as it were. Is this changing our view of the world?

That’s a very nice way of putting it. In America, you will find what’s called ‘new frontier thinking’. People had to go farther and farther West, and when that was no longer possible, they went into space. Now there’s a new space. Was that a logical development of what came before? Our view of the moon helped us understand that we are all crowded together on a planet, indiscriminately, a little bit lost. Simulation theory has provided us with an analogy – one that the film The Matrix made popular. We are not just capable of creating simulations; we could even live in one ourselves. How real is the world that I see? But this means that even more is at stake: Just what remains real to us? Is there some higher reality?

“Electronic depictions – virtual places – are not going to crowd out physical places. They are simply alternatives”.

These questions all open up areas of uncertainty.

Yes. I would find it exciting to investigate whether certain trends in the humanities are mental children of these questions – such as when people claim that absolute reality no longer exists, and that everything is relative. In simulations, everything could always be different. Even in Antiquity, there were theories that assumed that the world was something that had been created; that means there must have been someone who created it. If we live in a simulation, someone must have made the simulation. That’s a question about the existence of God. New religious ideas are springing up.

Let’s get back to something concrete. Have spaces lost their three-dimensionality?

It’s true that it’s difficult to describe this in traditional categories. We sit at our screens, and a whole world opens up behind them that does not need any physical place. Our computers are very small, but we can use them to create almost endless new spaces. This is quite intangible. Nevertheless, how things are depicted follows the three dimensions, otherwise we would be unable to comprehend them.

“Even virtual places can be cosy or sterile”.

They are places that don’t need any space …

All the same: every virtual space is created in a device, and our computing centres do need a lot of space. We need people to build these machines in the physical world, to service them and repair them.

Until now, we’ve used our computer screens to go into different spaces. But the reverse is also possible, using technologies such as augmented reality or holograms.

I’m still unsure about finding the right concept to be able to get to grips with this. Is it really such a big difference if I have a projection in my room by means of a hologram, or whether someone is speaking out of my TV? And if we go through a city wearing smart glasses that show us information as we walk: is this really much different from using a map when I go somewhere?

Spaces and places: what’s the difference between them?

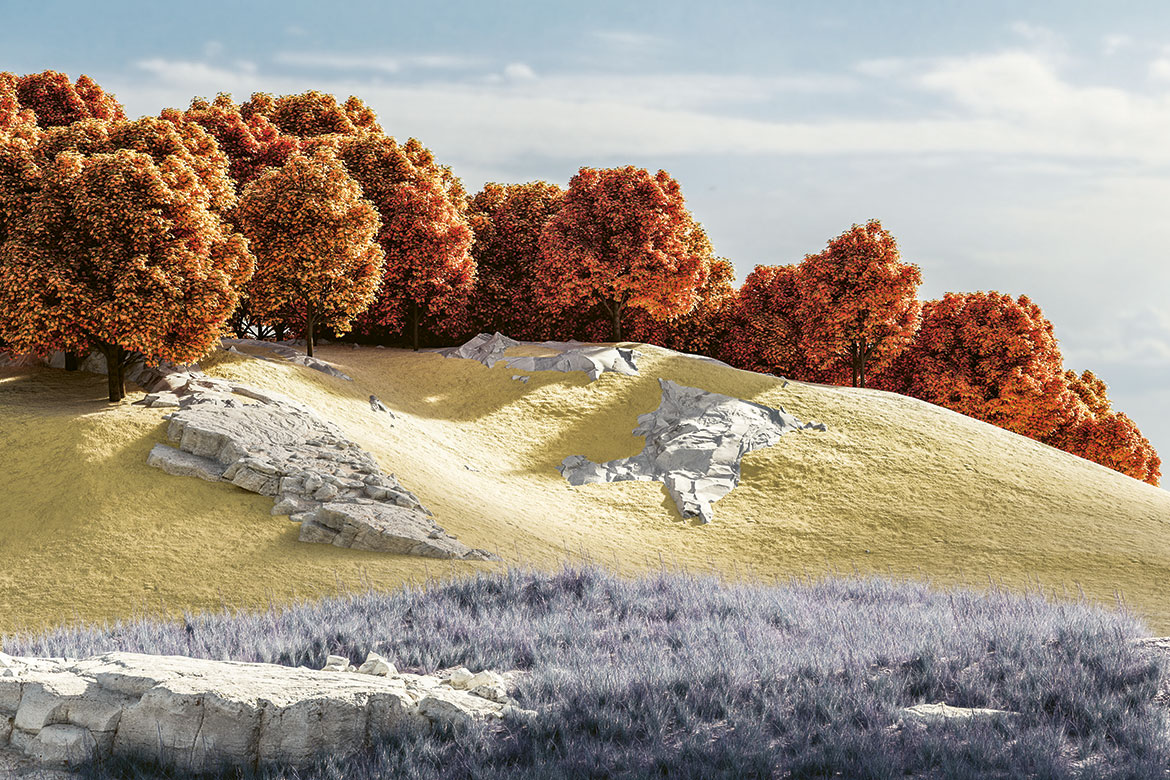

A space is a geometric category with length, breadth and height. A place is somewhere we are located. We are each sitting in an attic room, I see. They could theoretically both have the same dimensions. But the difference between them is on a local level: One is your home, the other is mine. What makes a place is something we can’t explain with geometrical descriptions. Whether it’s a virtual landscape in a computer game or an e‑banking website: even virtual places can be cosy or sterile.

“Our computers are very small, but we can use them to create almost endless new spaces”.

One special aspect of a virtual place is that you can’t touch it …

For us human beings, it’s important that the world should provide us with resistance. This happens in our bodies by means of hunger and thirst. Objects such as the glass from which I’m drinking have weight, and I can push against my table. I move within the world by overcoming the resistance it offers me (or not). All this is lacking in virtual places. We can sometimes use haptic feedback by means of vibrations, but it’s not the same thing. I am convinced that electronic depictions – virtual places – are not going to crowd out physical places. They are simply alternatives.

What’s your favourite virtual place?

I really like computer games, especially Minecraft. There is no goal to it; you could walk in a straight line for days, for example. But most people build houses in it. And furnish them. Though there’s absolutely no need for that. It reminds me a lot of Martin Heidegger, who described dwelling as the original human relationship with the world. We human beings are in the world by dwelling in it. And this is what we reproduce in the virtual world. You could do everything in it. Instead, people build houses. It’s crazy.