Feature: Sports in the lab

“It’s not my health that motivates me to run three times a week”.

Boris Cheval researches into the positive effects of sport on health. He explains why it is paradoxically difficult to get started. And gives some excuses to those who are idle.

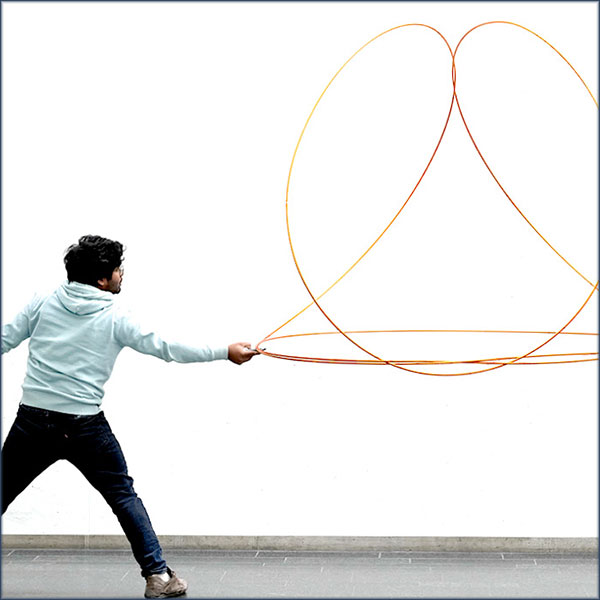

People have to believe that it’s their own decision to take part in sports. Only then will they remain committed, explains the sports psychologist Boris Cheval. | Photo: Hervé Annen

Boris Cheval, you are an expert in the health benefits of physical activity. I imagine you’re the sporting kind?

Yes, I am! I run and play football.

But not everyone does…. So, what is our relationship to physical activity?

It is an old one: at some point in evolution, our species set out to discover its environment. Since then, physical activity has been an integral part of our way of life. The human species is one of the few that needs physical activity – or sport, although I reserve this term for physical activity practised in a specific setting, such as a club – to stay healthy. The latest recommendations from the World Health Organisation are 30–60 minutes of physical activity per day. In comparison, great apes are not very active, but this physical inactivity does not threaten their health.

Yet we tend to do as little as possible.

This can also be explained by our evolutionary history. For a long time, avoiding unnecessary effort was a matter of survival since resources were limited. This is generally no longer the case today, but our brain has retained this habit: it evaluates energy expenditure and, where unjustified, it seeks to avoid it. We are therefore spontaneously attracted to sedentary opportunities, which unfortunately are becoming more and more numerous. And even in physical activity, we always converge towards an energy optimum. Numerous studies in physiology and biomechanics confirm this. Moreover, if we observe high-level athletes, we notice that their movements are much more efficient than those of beginners.

So, what does motivate us to play sport?

We need a strong trigger. Social pressure about our body image and health promotion messages may encourage us to begin physical activity, but rarely to keep it up. You need to feel you initiated your physical activity, that it’s your choice, otherwise you won’t maintain it. It may be the pleasure you get from it, the fact that you are in a group, or some other goal. These are the internal motivations that work for physical activity. And they result from the satisfaction of basic psychological needs. If the behaviour satisfies these needs, individuals will seek to reproduce it.

Examples of such internal motivations?

Take children who start to walk: they don’t want to stop. They are making great efforts, but they have a precise objective: to learn. Once they have learned to walk, you will see that they prefer to be carried: it’s an energy saver! Parents will then have the same experience: their children complain about walking to the playground, and once there, they run, jump and exert themselves. It sounds contradictory, but it is not: on the way, walking is a useless expenditure of energy, whereas at the playground, the activity is associated with positive emotions, with socialisation: in this kind of situation, the commitment to the effort is easy.

What encourages you to do sport?

The pleasure and well-being it gives me. I also go running when I feel my cognitive abilities need a boost. I keep my health in mind, but that’s not what motivates me to run three times a week.

What are the health effects of physical activity?

Benefits are observed in most people. Many studies show that it bears a positive influence on depressive symptoms and improves cognitive functions, e.g., memory, attention, reasoning and spatial orientation. It also has an impact on physical health, reducing the incidence of cardiovascular disease, certain cancers and diabetes. The benefits can be seen at any age, although being active from childhood onwards builds up a better health capital. Research has even shown that physical activity in pregnant women has positive effects on the foetus. For people who are ill, physical activity helps them deal with fatigue and the side effects of treatment. The most recent studies show it also helps to reduce the risk of serious COVID‑19.

Can we measure the impact of these benefits?

Well, the World Health Organization has stated that, in 2020, five million deaths worldwide were caused by a lack of physical activity.

Can physical activity also have negative effects?

It can lead to addiction. This is the case for about 2–3 percent of physically active people. Some studies even suggest that these people may be predisposed to experience what is known as the “runner’s high” in a relatively intense way. In these people, the well-being experienced is such that it leads them to repeat the effort, and from there it intensifies. This is exactly the same mechanism of addiction found in other types of behaviour. At the same time, this excess of physical activity can lead to injuries, social isolation and withdrawal problems.

Running is not the only way to have fun. It can also be had by going to a football match, although in this case you are rather inactive...

Yes, and it’s an ancient practice. In the games of Ancient Rome, you went to the spectacle, you saw people die, and it was perhaps a way of satisfying certain impulses. Today, in a football stadium, you can pour out your pleasure or your hatred more freely than elsewhere. Beyond the personal practice with health benefits, sport can also be used for political or educational purposes. It’s an excellent way to reach the general public.