REPORT

Of monks and butterflies

The historian Ivo Berther is delving into the everyday life of Benedictine monks and collecting their life stories. We visit a monastery with him.

Time doesn’t stand still, not even in the Einsiedeln Monastery. Father Jean-Sébastien is one of the younger brothers. His decision to become a monk was taken very consciously and after much reflection. | Image: Christian Grund

It’s a grey morning, and soon it will be nine o’clock. The historian Ivo Berther walks across the broad square in front of the Abbey of Einsiedeln. He goes past the Frauenbrunnen fountain with its copper-gilt statue of St Mary, and past the world-famous collegiate church. He enters a gate and walks along the thick stone walls of the monastery. In the abbey courtyard, a monk dressed in a black habit comes up to him.

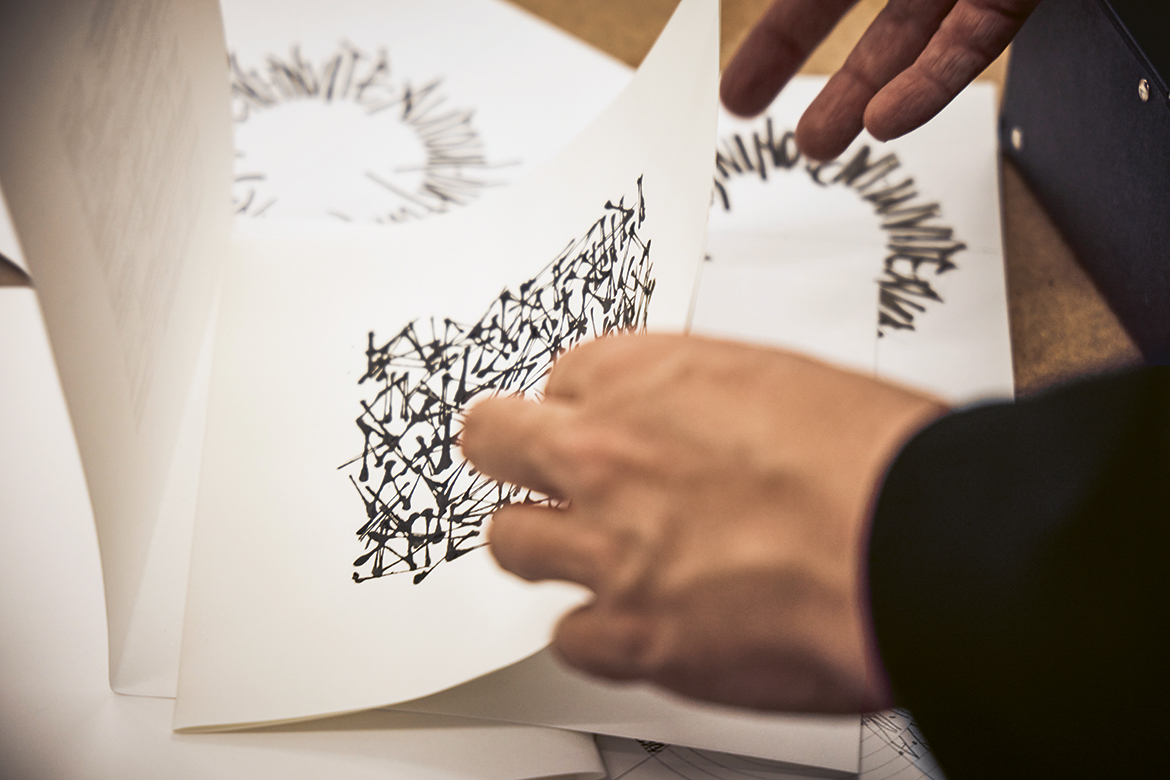

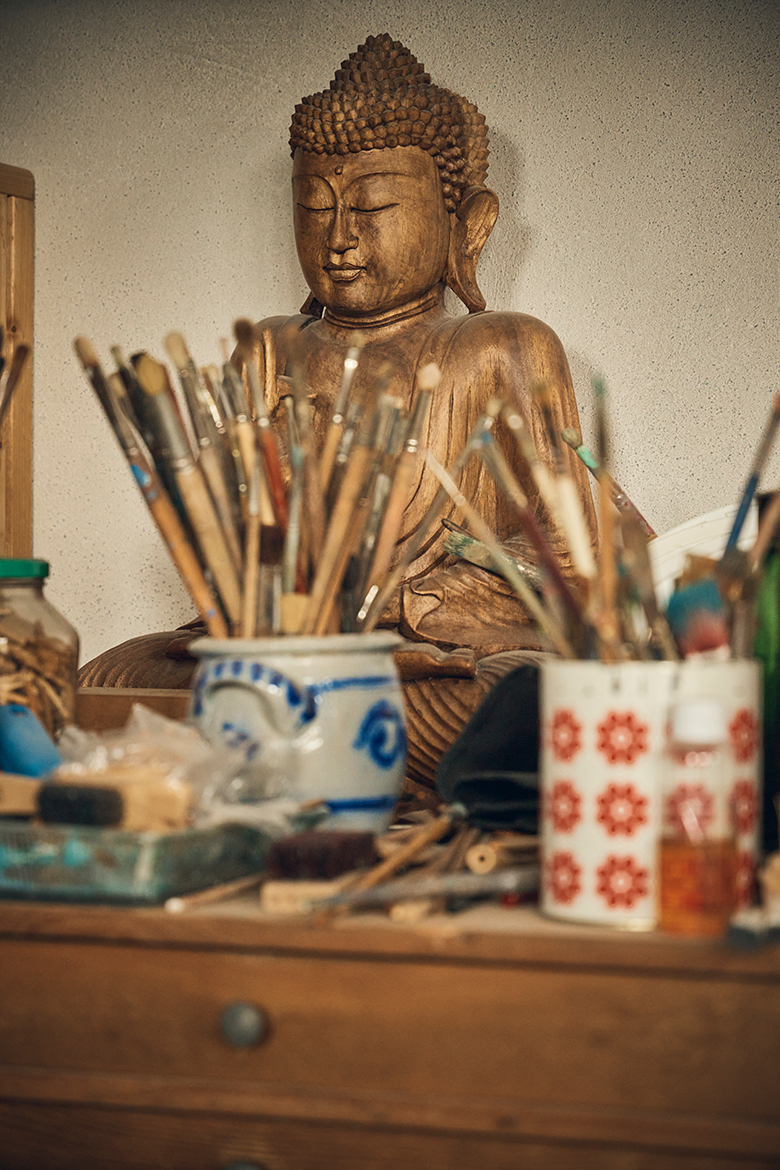

Father Jean-Sébastien has been up for over four hours, and has already been to prayers twice. We enter his calligraphy workshop, where he offers Berther a chair and a cup of coffee. This is his second visit here in order to learn the life story of this 49-year-old Benedictine monk. In this small, sparse room, paper for painting is stacked in the bookshelves, and jars full of coloured pencils and crayons are standing on the large wooden tables. This is where Jean-Sébastien teaches his regular calligraphy workshops for outside visitors. He learned his craft in the 1990s at the Academie de Meuron in Neuchâtel, where he completed his studies with a thesis on Buddhist art in Tibet. Afterwards, however, he renounced a career as an artist, just as he left his life among family and friends. At the age of 27, he decided to live with a hundred, like-minded men in the Monastery of Einsiedeln, which was founded in 934 AD. Despite occasional crises, he has never regretted taking this step, and says so cheerfully.

Monks are like researchers

Berther sits down at the table, which is stained with different colours. He fishes a black recording device out of his rucksack and puts it on the table in front of Jean-Sébastien, who’s sitting opposite him. Then he puts a second device next to it, so he has a back-up in case one device doesn’t work. After all, the conversations he is recording will form a core part of his doctoral thesis.

He has been working on his doctorate in ecclesiastical history at Lucerne University’s Faculty of Theology since August 2019, and is carrying out interviews in monasteries as part of the research project ‘Life stories of Benedictines in Switzerland’. Berther is primarily interested in the way of life of the monks, their identity, and their construction of masculinity. A female colleague in his department is doing the same with nuns in convents. Both researchers are working with oral history methods. In long conversations, they use highly open questions to gain information on the way of life of the nuns and monks. They are planning on carrying out 70 interviews in 21 monastic institutions by the end of the project in late 2023, most of them in German-speaking Switzerland.

In the workshop, a red light shows that the devices are recording. Berther asks his first question: “Father Jean-Sébastien, why did you become a Benedictine monk, and why are you still a monk?”. Father Jean-Sébastien replies in High German with a slight French accent, choosing his words carefully. “It’s like when you’re thirsty or hungry: You seek out a place where you can drink or eat”. Berther doesn’t have a list of questions, nor any paper or notes in front of him. He concentrates completely on the monk’s answers, and adjusts his next questions according to what is said. Within a few minutes, Jean-Sébastien is talking about the great questions of life: truth, love, faith and tolerance. To him, monks are primarily searching for something – “rather like researchers”.

Nothing works without trust

The interview lasts for about an hour. Afterwards, Jean-Sébastien invites Berther to midday prayers, followed by lunch. They chat as they walk around the extensive monastery complex. It has its own school, fire brigade, wine cellar and horse stables. It’s rare for other monks to cross their path - but when they do, they greet each other cheerfully and politely, as if they are all aware at all times that they need to cultivate their lived community. On the way to the church, Father Jean-Sébastien talks more about the world than about God. He mentions the TV series ‘Game of Thrones’, which he liked a lot, and a visit he has made to CERN in Geneva. He is very interested in quantum physics because, he says, it allows for alternative explanations for natural phenomena.

“Like most people, I too had preconceptions about monks being detached from the world and closed off”, admits Berther. “But up to now, I have mostly met people who are incredibly curious, funny and even highly progressive”. He has stayed overnight in monasteries several times so that he could participate in the daily routine of the monks. These experiences help him to understand the monks’ narratives better, and to contextualise what they say. “But what’s more important is that it helps me to build up trust”, says Berther. Without trust, he says, oral history is just not possible.

It’s now shortly after 11 a.m. Midday mass will begin soon. Berther accompanies Jean-Sébastien into the collegiate church, a Baroque edifice built in the 18th century. Inside, you are immediately overwhelmed by a sea of biblical images. Jean-Sébastien has meanwhile changed his clothes. He’s wearing a long, white cassock, with a red velvet stole over his shoulders. Together with six fellow priests he stands in the centre of the back section of the nave that is not accessible to laypeople. The huge space is soon filled with the singing of the monks – and with the smell of the incense from the chain censers that the altar boys have been swinging to and fro. Then the organ begins to play and the congregation joins in.

After the closing prayer, the monks go to their refectory. Today is a special day for them. It’s the “Feast of the Cross”. Their dining hall is suitably adorned with festive decorations, and they eat a meal of semolina soup, meat balls, ratatouille and mashed potato while a monk reads from the Greek legends of the Cross. The mood is both solemn and devout. After the reading, they chat. But this is an exception, for they normally eat in silence.

A generational rift?

Berther has already begun analysing his observations and interviews. He does so using so-called grounded theory, a methodology derived from the social sciences. He orders the content of his transcripts according to specific categories, such as ‘youth’, ‘crises’ or ‘reasons for joining’, which enables him to group together comparable sections of his different texts. His aim is to deduce social phenomena from all these subjective experiences and gradually to arrive at an overarching theory.

Berther’s preliminary findings point to the emergence of a generational rift: “Younger monks, like Father Jean-Sébastien, mostly come to the monastery after having begun their professional lives. They have chosen to enter the monastery in a very conscious way, and after much reflection”. But with the older monks, their decision was often already taken at an early age, after attending a monastery school. “For students from poorer backgrounds in particular, entering a monastery was often the only chance they had to study anything”. Berther has also observed generational differences in the monks’ self-image: “For example, the younger monks have started to wear their black habits again, even in public”. This is difficult for their older brothers to understand, many of whom had fought for things to change back in the 1960s – including the abolition of any obligation to wear their habit in public.

Once the research project has been completed, the anonymised transcripts of all these interviews will be deposited in the archives of the monasteries and convents themselves, and thereby made available to the nuns and monks. This is in the hope of keeping the culture of their orders alive. Since the 1970s, most monasteries have been suffering from a drastic loss of membership. The Einsiedeln Monastery is the biggest in Switzerland, and when Jean-Sébastien entered 22 years ago, it was home to about 100 monks. Today there are just 40. In total, the Benedictine Order in Switzerland only has 230 monks, most of whom are over 70 years old.

Of eternity and the dying of the monasteries

“It’s foreseeable that many monasteries will have to close, merge or transform over the course of the next 50 years”, says Berther. This fall in numbers is already having serious consequences: “Almost a third of the monks we’ve interviewed so far told me that they were suffering from psychological problems because of their heavy workload”. As the monastic communities continue to shrink in size, the work of maintaining the monasteries and serving the general community is falling on fewer and fewer shoulders.

During their conversation that same morning, Berther asked Jean-Sébastien about this slow death of the monasteries, and wanted to know if this development frightened him. Father Jean-Sébastien smiled and replied with a proverb from Asia: “What the caterpillar calls death, the wise man calls a butterfly”. This Benedictine monk has a relaxed attitude to the transience of things. He knows that everything has its time: “Nothing is forever – except eternity”.