IN PICTURES

The monster exposed

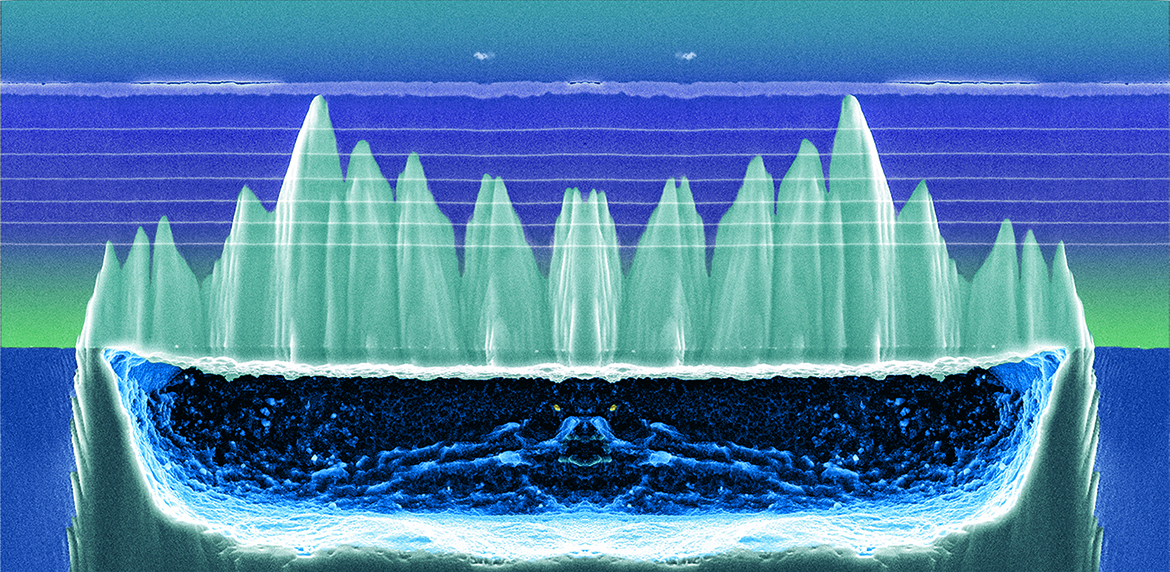

Under an electron microscope, fantastic detail can be seen in a tiny spot of corrosion on the barrier film of an implant.

“I imagined the spider when I saw this image”, explains Kyungjin Kim, a former postdoc in mechanical engineering. | Image: Kyungjin Kim

“It took me seven months of work to get a result”, says a smiling Kyungjin Kim, who is an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Connecticut, United States. And what a result! It’s a tiny spot of corrosion, invisible to the naked eye. Indeed, in this image, there is no monstrous spider under a sky of northern lights, but the wear and tear of a barrier film observed with an electron microscope. This detail is barely 100 square micrometres.

During her postdoc at EPFL, Kim studied the longevity of implantable electronic devices such as neuroprostheses. Without protection, the life span of these extremely thin implants in the human body does not exceed one month. To improve this, the scientist encapsulated an implant in a barrier film consisting of a polymer and six dyads of ultra-thin metal oxides. And then she put it to the test. Actually, she immersed it in a solution that mimics the conditions of the human body, but at a temperature of 80 degrees Celsius. This accelerated the wear and tear of the film by about 20 times. For a long time, nothing happened. Then a small area of damage appeared. To find out what caused it, the scientist looked at it under the electron microscope, finding corrosion.

And that’s what you can see in the picture, which is flipped vertically. The horizontal lines are the layers of the barrier film; the thickest one at the top is the part in contact with the electronic device. What looks like mountains is actually an artefact that appeared when the film was cut. And the spider is part of the polymer in the barrier film. “I imagined it when I saw the image, and to reconstruct it, I doubled the mirror image. I also coloured it to give it that northern lights vibe, because it was black and white to begin with”, says Kim. Beyond this aesthetic result, the image also allowed the scientist to verify that the protective film she had developed had done its job properly.