Peer review

Tracking down gender bias

We still lack good data for determining gender bias in scholarly publications. The Royal Society is adopting a new approach.

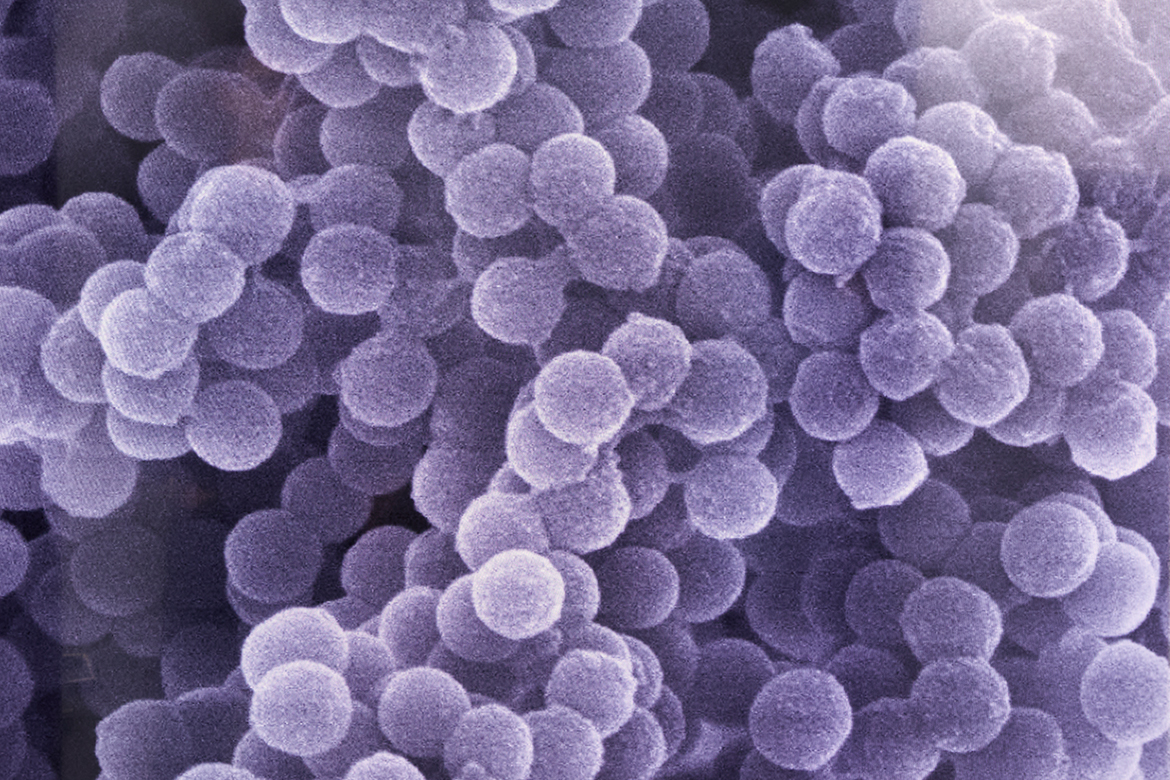

During the pandemic, women scientists submitted noticeably fewer works for publication than their male colleagues. | Image: Wikipedia

In a blog post for the Royal Society, the publisher Phil Hurst has proposed that all scholarly publishers should collect data on possible gender bias in their peer-review processes. He feels that the need for this has been confirmed by two events. First, the Royal Society of Chemistry published a report in 2019 that proved the existence of gender bias in their publications. Secondly, various studies have shown that female scientists submitted significantly fewer manuscripts to specialist publications during the pandemic than did their male colleagues. Hunt writes that the Royal Society has been asked several times as to whether the same pattern has become evident in its own journals.

The Royal Society is one of the oldest scientific societies in the world. Until now, it has collected gender data by means of surveys of editorial boards, authors and peer-reviewers. But Hurst maintains that this method has several weaknesses on account of the meagre response rates and the way in which the respondents are approached. It is therefore not fit for identifying bias during the peer-review process. This is why the Society is now collecting gender data from the online peer-review systems of journals such as Scholar One Manuscripts and Editorial Manager. Everyone submitting a paper will be urged to describe their gender using a pre-set list. “We are being transparent about who will have access to this data, and how it is going to be used and protected”, says Hurst, who can confirm that about 95 percent of those submitting responses have been indicating their gender. “This simple approach does the trick: it allows us to conduct a better assessment of bias at every stage of the process: when an article is rejected outright, during the triage process, in the recommendations of the reviewers, and in the decisions made by the editors”.