ORGAN DONATION

Who gets whose kidney?

Not everyone who needs a new kidney has the same chance of getting one. A new study shows who is more likely to benefit.

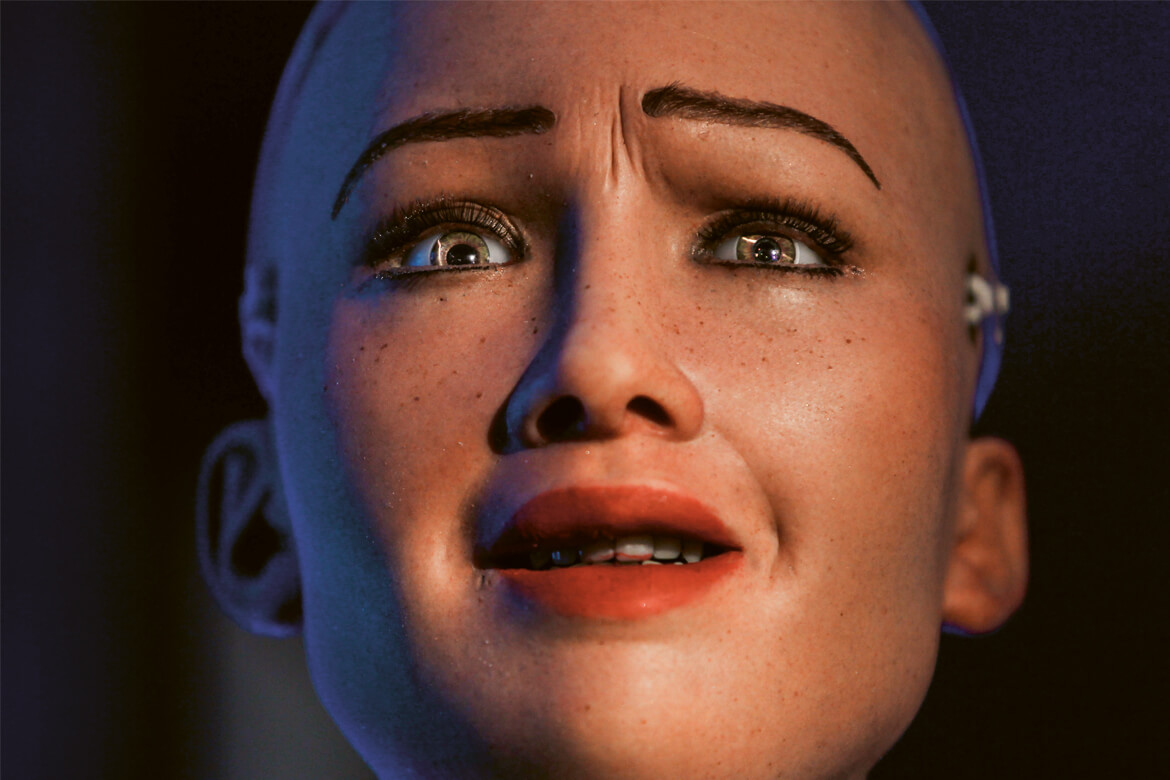

Mothers will usually give their children a kidney if they need one. But they will rarely accept a kidney from one of their children. | Image: Sören Stache/DPA/Keystone

In Switzerland today, one third of all kidney transplants are living donations. Their dual advantage is that they are less likely to be rejected than organs harvested from the deceased, and that the waiting time for one is significantly shorter. The risks involved for the donors are manageable. But a recent study has now shown that not everyone has an equal chance of getting a kidney from a living donor.

This investigation was carried out as part of the Swiss Transplant Cohort Study, STCS. The team responsible was able to interview almost all 2,000 people who had undergone their first kidney transplant between 2008 and 2017. The results showed that people have worse chances of receiving a living donation if they are older, or less educated, not fully fit for work, or not in a steady relationship.

But why should your age or level of education influence your chances of a living donation? The problem is that as you get older, the probability decreases of your getting a suitable donation from your parents, siblings or partner. “The most obvious donation is from a parent to a child – more precisely, from a mother to a child. There is hardly ever a case where a potential donor says ‘no’ when it’s a parent”, says Jürg Steiger, Chief Medical Officer (CMO) of the University Hospital in Basel, and the principal investigator of the STCS. But for most patients, it is simply out of the question to accept a kidney donation from their own child, or in fact from any much younger person. Every third living donation actually comes from the patient’s spouse.

What’s more: people who are better educated generally know more about the benefits and risks of a living donation, so are more likely to have the courage to broach the topic among those around them. Not simply in the sense of asking straight out for a donation – most people find that difficult – but to create clarity. “The offer usually comes from the donor themselves”, says Steiger. The currently unequal opportunities in matters of living donations can begin to be mitigated by providing targeted information and by having detailed discussions with doctors. Spouses and other family members should be involved in this as soon as possible.