Cybersecurity

How Switzerland is preparing for cyberwarfare

For decades now, we have been living in fear of cyber-attacks that could conceivably cripple the infrastructure of an entire country in one fell swoop. Is Switzerland properly equipped to cope?

Virtual attacks can have concrete consequences. The so-called ‘Colonial Pipeline Hack’ in May 2021 meant that most petrol stations in the region around Benson, North Carolina in the USA were unable to sell any petrol. There was panic buying at the few stations left that still had supplies. | Photo: Sean Rayford / Getty Images

Russia’s military strategy in its attack on Ukraine is reminiscent of tactics used in the Second World War. And yet analysts had predicted a completely different kind of conflict: a cyber war, in which digital attacks on critical infrastructure by Russian hackers would have supposedly left Ukraine defenceless.

As we now know, however, everything turned out very differently. Battles have been undoubtedly fought in the digital sphere – already back in January, for example, suspected Russian hackers took over websites of the Ukrainian government and posted threats there. But Russia in turn was later targeted by the hacktivist collective ‘Anonymous’, who shut down websites of the Kremlin, the Russian Ministry of Defence and the energy company Gazprom. They allegedly also gained access to Russian state television. But these attacks did not last long, nor did they have much of an impact.

We can all be affected

“That’s the problem with cyber operations like that. You can attack, but you don’t know if the enemy has a backup option to restore its networks quickly”, says Myriam Dunn Cavelty. She is a senior lecturer in security studies, a member of the Advisory Board Cybersecurity of the Swiss Academy of Engineering Sciences, and a consultant to the federal authorities and the Swiss Army. “We are not better or worse protected than others”, she says. “The Internet is an insecure technology. Information exchange played a role in its development, whereas confidentiality didn’t play any role at all”. She says that there are indeed projects investigating how we might encrypt digital communication, such as ‘Scion’, a technology developed by ETH. “But this would not make the Internet fundamentally more secure”. This is why she emphasises that our future is going to be characterised by different shocks: “We are going to be hacked, and we will have to learn how to deal with that. We should already be asking ourselves: How are we going to manage such an incident? And how are we going to restore both technological and societal functionality?” For all the positive aspects of digitalisation, it has also increased risks, she says: “Basically, anyone can become the target of cyberattacks because we are already all part of something bigger”.

But what about the ‘electronic Pearl Harbor’ that people fear so much, i.e., a large-scale cyberattack that could cripple the critical infrastructure of an entire country in one fell swoop? “So far, this is only something that people talk about”, says Dunn Cavelty. Of course, she adds, there are theoretical threat scenarios such as attacks on logistics, payment transactions, fuel supplies, health care or electricity supplies. “But I’m not so pessimistic about all that because I have repeatedly seen how we can fall back on other systems or improvise”. This is rather like Elon Musk’s Starlink satellite network, which is now providing Ukraine with Internet access from a low-Earth orbit.

For Dunn Cavelty, the war in Ukraine shows one thing above all: “The usefulness of cyberweapons for the military is much lower than we thought would be the case, over 20 years ago. However, it’s very different for the intelligence services and organised crime”.

As a result, companies and private individuals are becoming the focus of attention, not just nation states. We can observe this in Switzerland, too, where ransomware attacks have become more frequent – in other words, attacks using malware that encrypt data on a large scale. Only when you’ve paid a ransom to the hackers can you access your data again. “Broadly speaking, this increase in ransomware attacks is a definite trend”, says Pascal Lamia of the National Cybersecurity Centre (NCSC). “Unfortunately, for as long as people pay these ransoms, the business remains profitable for the attackers”.

Poorly secured systems offer gateways to attackers, meaning that they can rake in quick money without expending much effort. Since 2020, the NCSC has been making statistical evaluations of the cyber incidents that are reported to them. There were 11,000 in the first year, then twice as many in 2021. Since there is no obligation to report cyberattacks in Switzerland, the number of unreported cases may be much higher still. Not all these reports were of successful attacks; they also included phishing attempts, for example.

Open-source software for more transparency

Hernâni Marques is a board member and press spokesman for the Chaos Computer Club (CCC) in Switzerland, an association of hackers that is campaigning for more security and privacy. He believes that media literacy should be taught at schools. To him it’s obvious that everyone has to take on more responsibility for cybersecurity, “because the net is permeating the whole of society”. Marques is observing developments with a great sense of caution.

He sees a core danger in the fact that sovereignty over hardware and software is completely in the hands of the Chinese and Americans. “On Apple products you read: Designed by Apple in California. Assembled in China. That’s how it is with most computers”, he says. “If we order components for our critical infrastructure, the supplier knows about it. I wouldn’t go so far as to claim that every PC has been infiltrated. But China would be able to insert bugs in targeted production lines”. This is why he believes that European countries need to repatriate technical expertise, and develop and build devices themselves.

Another key factor in Marques’s opinion is transparency. Most operating systems work with proprietary software whose code is inaccessible. But a diametrically different format exists: those programmed with open-source code. “With such software, we could check it and see if it’s reading along, or has built a backdoor into the system”. But governments have little interest in this – their intelligence services least of all. They need such backdoors for surveillance purposes. According to the spokesperson of the CCC, some nation states even buy security loopholes on the black market – in other words, they are using taxpayers’ money to finance organised crime.

One solution, believes Marques, would be to separate the authorities responsible for cybersecurity from the intelligence services. In other words, nations should keep their offensive and defensive interests apart. That isn’t the case today. In Switzerland, for example, the Federal Intelligence Service is in close contact with the NCSC.

Swiss cooperation with the FBI

Switzerland is also home to unsuspicious cases of cooperation with intelligence services. These include the project ‘abuse.ch’, which was set up by Roman Hüssy from the Institute for Cybersecurity and Engineering at the Bern University of Applied Sciences (BFH). This platform identifies and analyses harmful websites, thereby supporting security experts by providing technical information on current cyberthreats.

What’s neat is that this data is made available publicly and free of charge: it’s a case of ‘open source threat intelligence’. It benefits international authorities such as the FBI, which has already used the data to initiate proceedings against cyber criminals. “But manufacturers of IT security products also rely on data from abuse.ch”, says Hüssy.

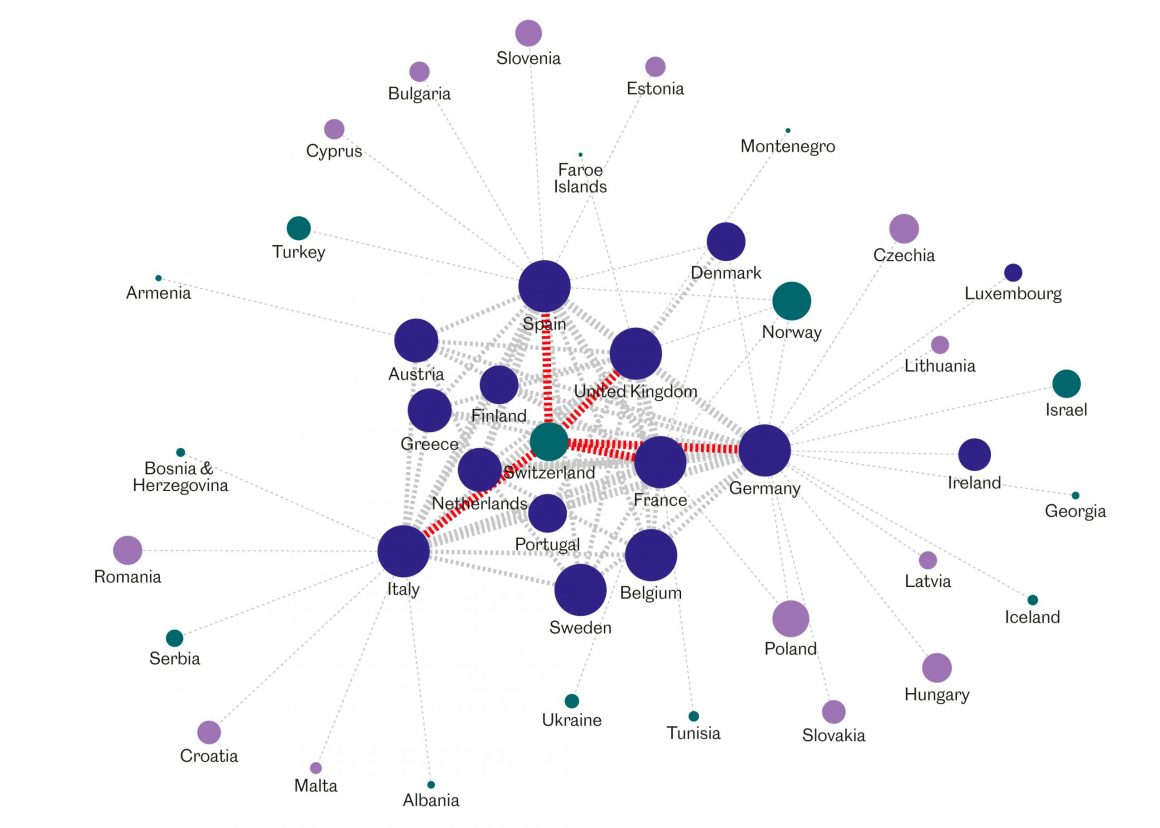

Since June last year, BFH has been working together with abuse.ch and has secured the funding for the project’s infrastructure by means of donations. In return, abuse.ch shares raw data with BFH for research and teaching purposes. For example, this means the structures of botnets or the spread of malware can be better investigated. There is certainly plenty of material available: “Within two years, we have discovered more than 2,000,000 malware sites, and made a significant contribution to having them taken off the net”, says Hüssy.

Thinking and acting ahead

Meanwhile many Swiss universities have included cybersecurity as a subject on their curricula. “The focus is primarily on technological aspects”, says Dunn Cavelty. “What’s lacking is interfaces between politics, IT, law and forensics”. In her view, cyber issues can no longer be considered in isolation. Advances in algorithms are moving us towards artificial intelligence, so the future of digitalisation is not going to be simply a matter of technology. Dunn Cavelty is convinced of it: “All societal questions are going to acquire a socio-technological aspect. If we want to answer those questions, we’re going to have to start creating appropriate training opportunities now”.