Provenance research

“Uncertain provenance is the norm”

What’s the state of provenance research in Switzerland, eight years after Cornelius Gurlitt’s unexpected legacy to the Bern Museum of Fine Arts? Nikola Doll is the head of the Museum’s provenance department. She explains to Horizons why she is unlikely to run out of work any time soon.

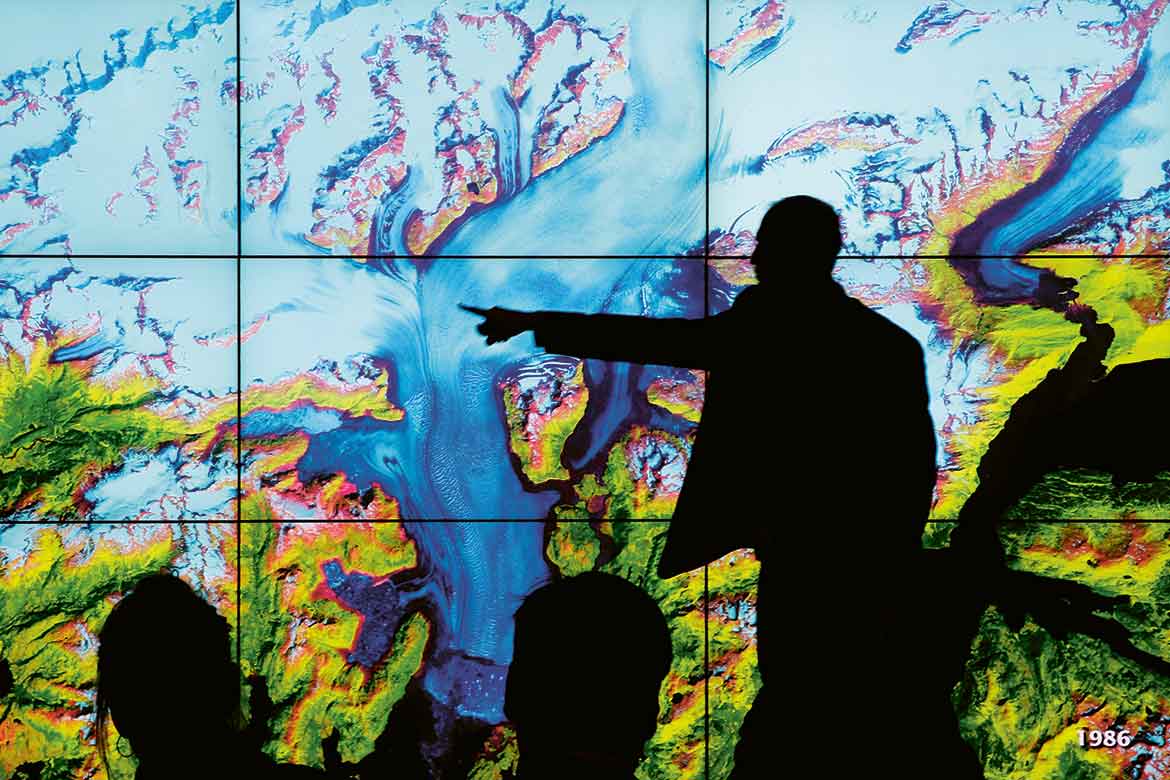

The ‘Gurlitt Case’, in which an art dealer left his estate to the Bern Museum of Fine Arts, has helped to make provenance research more systematic and more transparent in Switzerland, says Nikola Doll, an expert in looted art. | Image: Ruben Wyttenbach

The National Council has decided that Switzerland ought to have a Commission on Looted Art. Why do we need such a thing?

In 1998, Switzerland and 43 other countries adopted the so-called Washington Principles for dealing with art confiscated by the Nazis. Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom – and, most recently, France too – have meanwhile set up commissions to act as arbitration bodies in disputed cases. It’s become clear that Switzerland’s museums and collections evaluate instances of looted art in different ways. From a research perspective, it would be desirable to establish a set of harmonised standards for evaluating these cases.

The Bern Museum of Fine Arts is regarded as a model institution in dealing with potential cases of looted art – quite in contrast to the Kunsthaus in Zurich, which has been criticised heavily for the way in which it has handled the Bührle art collection. Why have they approached things differently?

The issues at stake are the following. Is the institution in question a large museum with the appropriate capacity, or is it a small house? Does it have holdings that underwent changes of ownership between 1933 and 1945 about which nothing is known, or which are undocumented? Are some works already suspected of having been looted by the Nazis, or have claims even already been made for their restitution? Cornelius Gurlitt’s estate encompassed some 1,600 works of art. When the Bern Museum of Fine Arts accepted it in November 2014, it forced us to address these issues actively and transparently.

Has the Gurlitt case overall given a boost to provenance research?

When those artworks were discovered in Gurlitt’s apartment in the Munich district of Schwabing, Nazi art theft and provenance research became the focus of a public debate about socio-political issues. And when the Gurlitt legacy was accepted by the Bern Museum of Fine Arts, these issues also entered the public consciousness in Switzerland. For the museum, accepting the legacy also meant establishing a systematic process of provenance research that entailed a transparent discussion about the subsequent findings. This is why it published the database ‘The Gurlitt Estate’ last year. In 2014, however, the general question arose in Switzerland as to what had happened since the adoption of the Washington Principles in 1998 and since the report of the Bergier Commission.

How did the Swiss authorities react?

One result was that the Federal Office of Culture began awarding grants for provenance research to Swiss museums in 2016.

But works of art changed hands in all manner of ways during the Nazi era – besides expropriation and forced sales, some were sold quite normally on the art market ...

The National Socialists did not just steal art by means of confiscation without compensation. The German state used laws, decrees and special taxes to deprive Jews and regime opponents of their livelihoods, step by step. It was in this context that valuable objects were sold, such as works of art or jewellery. In provenance research, we reconstruct the circumstances under which an object came onto the market. Was it sold voluntarily, under pressure or threat of violence, or because the owners were in economic hardship as a result of persecution?

Does provenance research also engage with the situation of the artists themselves at that time? I’m thinking in particular of the Nazis’ ‘Degenerate Art’ campaign.

It was within the framework of that campaign that works of modern art were confiscated from German museums and collections. It was done on the instructions of Adolf Hitler himself, implemented by the Ministry of Propaganda, and legitimised by law in May 1938. The ‘Degenerate Art’ campaign was a component of the Nazis’ art policy and was intended to have an impact on museums. Artists were not the primary target of it.

But weren’t some of them banned from exercising their profession?

The National Socialist state controlled German cultural life through the Reichskulturkammer, the ‘Imperial Chamber of Culture’, which was founded in September 1933. Anyone who wanted to work as a visual artist or art dealer had to be a member of the Chamber. Opponents of the regime were barred from membership of it; after the enactment of the so-called ‘Nuremberg Laws’ in September 1935, all Jews were in any case excluded. But it was rare for explicit bans to be issued to prevent someone from exercising their profession.

But people often assume the opposite …

The fact that the National Socialist regime issued occupational bans was only emphasised regularly by people after the Second World War. In doing so, former protagonists made themselves out to have been victims, placing themselves on the same level as those who had actually been persecuted.

One example of this is Hildebrand Gurlitt, who portrayed his activity as an art dealer during the Nazi years as having been undertaken solely to save the modern art that had been defamed as ‘degenerate’. But he remained silent about his trade in the territories that had been occupied during the War, about his purchases from Jews who were being persecuted, and also about his purchases for the ‘Sonderauftrag Linz’, the ‘special mission’ to set up Hitler’s so-called Führer Museum in Linz.

The concept of provenance research is used almost solely with regard to National Socialism. Why is that?

Provenance research has always been an aspect of art history, of the history of museums and of the art business. The Washington Principles adopted in 1998 state that the theft of artworks and cultural property by the National Socialists was an important element of the genocide that they carried out. This changed what was expected of provenance research and how its findings should be handled. In recent years, however, provenance research has also become established in Eastern European countries with regard to the theft of property by the former communist governments.

The concept is also used for art looted in a colonial context.

That’s right. Today, provenance research has also become established in cases where cultural artefacts were stolen or relocated by colonial powers. This research is also funded by the Federal Office of Culture. In former colonies, such as those on the African continent or in Asia, there is an awareness today of how colonialism caused them to lose their culture and cultural objects, and they are making claims for the return of looted artefacts. Provenance research, however, also deals with the theft of art and cultural property in our own time – such as the looting of museums during the war in Iraq, or the excavations that were looted during the war in Syria.

Won’t your volume of work as provenance researchers begin to dwindle over time?

Actually, an incomplete provenance is the norm when works of art change hands. It’s only in rare cases that we have information and documentary sources on all the different owners of an artefact, from the moment of its creation to the present day. However, the persecution and murder of European Jewry, the concomitant looting, and the destruction of clear evidence about former owners present us with significant difficulties. Every gap in the record prompts questions. For the period between 1933 and 1945, a researcher will be able to carry out a reliable, basic investigation of the gaps in provenance for a maximum of 100 works of art in a single year. If there are indications that a work of art might have been looted by the Nazis, then that basic investigation will have to be followed by more extensive research that can take several years.

So the work you and your colleagues are doing is never going to end?

In practice, works of art with unexplained provenance are regularly re-examined. That’s because new findings may emerge when new archives are catalogued, when different data are subjected to digital consolidation, or when new search reports are published in the ‘Lost Art’ database or the ‘Art Loss Register’.