SCIENTISTS IN DANGER

Knowledge in suitcases

Scientists must sometimes leave their countries to continue their work, either because their countries are at war or because their work is controversial there. In Switzerland, the Scholars-at-Risk programme supports a number of them. They’ve been telling us their stories.

Najia Sherzay | Photo: Flavio Leone

“I wanted to be a source of inspiration and encourage young girls to study”.

“In 2021, the doors of the University of Kabul were suddenly closed to women as the Taliban returned to power. I was both a distance doctoral student in Malaysia and a biochemistry teacher in Kabul. I didn’t waste much time: my priority was to continue my training, even if it meant leaving my country. A friend spoke to me about the Scholars-at-Risk programme. My application was processed in just two days, but it took me a year and a half to leave Afghanistan with my family.

“Today, I have been taken in as a researcher at EPFL. I’m catching up on lost time so as to finish my distance PhD and at the same time I’m training in the techniques of my new laboratory, which are novel to me.

“I was well received by the Scholars-at-Risk network and by EPFL. My husband is also a researcher and he’s supported in administrative terms, e.g., in obtaining a residence permit to allow him to work. We have two children of five and six years who are educated and well looked after. Overall, we feel good in Switzerland and I’m happy to be able to continue my research.

“However, I’ve lost a large part of my motivation. At the University of Kabul, I was actively working to defend women’s right to education. In my country, there is an enormous amount of awareness-raising to be done. My position meant I was able to report certain instances of discrimination or harassment to the authorities. And then, above my own career, I also wanted to be a source of inspiration and encourage young girls to study. That’s no longer possible: armed men prohibit access to education. In so doing, and this is the worst part, they are prohibiting all hope, and many young girls are discouraged. I do what I can from a distance, e.g., taking my time to inform women of the possibility of obtaining scholarships to move abroad”. ef

Emirhan Darcan | Photo: Flavio Leone

“Suddenly I had to decide: Should I run away, even though it was actually illegal?”

“I have bittersweet feelings when I think about how I fled. I’m from Istanbul and grew up feeling European. For me, Switzerland has always stood for freedom, security and human rights. For this reason, my new home in Bern fills me with happiness. However, my wife, our three daughters and I have a difficult time behind us. After the coup attempt in 2016, freedom of expression in Türkiye was subjected to ever tighter restrictions. If you want to enjoy freedom as an academic there, it’s better not to address any taboo topics.

“In Ankara, I fell into danger because of my projects. I was researching into the prevention of extremism, and speaking up for the rights of women and children. I was put under surveillance by the state. Ultimately, I faced a sentence of up to 15 years in prison. I used to be a normal man with a career and a family. Suddenly I had to decide: Should I run away, even though it was actually illegal? That decision was very difficult for me to make.

“Every academic who’s been accused of terrorist propaganda – like me – has had their passport revoked, or has been reported ‘missing’ to Interpol. Since they’d also blocked all my bank accounts, fleeing to Greece and then on to Switzerland was extremely difficult. I had to hitchhike some of the way, and had no money for an Internet connection. Luckily, I was allowed to fetch my family to join me in Switzerland. We lived in eight different refugee shelters over the course of three years – each time with all five of us in a room 20 square metres in size. That was still the case during the Corona pandemic.

“It also took three years before the Scholars-at-Risk programme was able to get me a temporary research position in Switzerland. Today, I’m working at the Institute for Criminal Law and Criminology of the University of Bern. My current project is about Turkish prisoners in the Swiss penal system. I am working out how to organise their successful resocialisation in their country of origin after they’ve been expelled from Switzerland. We now live in a family flat, I’ve taken German courses and have joined several associations. Thanks to that, and to the support from my Institute and from Scholars at Risk, I feel properly integrated here”. kr

Akram Mohammed | Photo: Flavio Leone

“I was taken to undisclosed locations”

“I went to school in Yemen, but I took my bachelor’s and master’s degrees in computing education in Saudi Arabia, because I sought experience abroad. That’s also why, in 2015, I applied for a Swiss Government Excellence Scholarship, which I received and which allowed me to undertake my PhD in computer systems at the University of Geneva. During this time, as I explored Geneva, I started to become involved in education and human-rights defence. I participated several times in the sessions of the United Nations Human Rights Council. In particular, I raised the issue of the violations committed by the various parties to the conflict in Yemen.

“In 2018, I even provided training on human rights in Ta’izz, Yemen, which led to my arrest and forced detention over a period of four days in undisclosed locations, prior to being released on the condition I signed a document forbidding me from travelling abroad. Fortunately, my father helped me to leave the country at Aden airport, which was not under the control of the Yemeni authorities. I understand that the local police have returned on several occasions to look for me. In Yemen, I run the risk of arrest, disappearance, torture and even death, because I raised the question of human rights in my country.

“In Switzerland, I finished my PhD and was granted political asylum. My wife and three older children joined me in 2021. Our youngest was actually born here. Everything is going well, they’re in school and learning French – faster than I am! I’m now 43 years old and a postdoc researcher in IoT security. What next? I’m not exactly sure, but the Scholars-at-Risk network is helping me. I’m planning to stay in Switzerland; I’m comfortable here.” ef

Olha Marinich | Photo: Flavio Leone

“I felt like an animal that’s struggling simply to survive”.

“The windows were smashed in where I used to work in the Kyiv region, our computers were looted by the Russian Army, and they destroyed our water supply and heating. Inside it was freezing cold, and we only had a few hours of electricity a day. People found explosive devices outside. Even now, the sirens wail almost every day. It was simply no longer possible to concentrate on my work or to lead even a halfway normal life. I felt like an animal that’s struggling simply to survive.

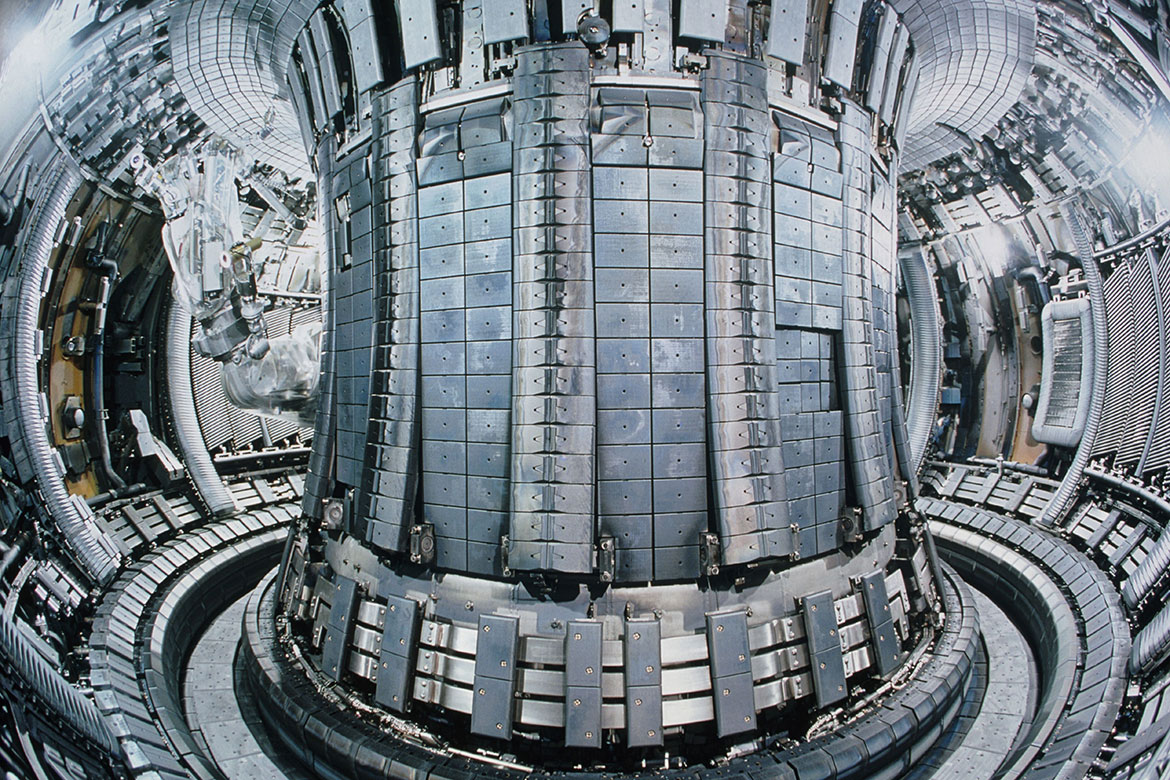

“Since the summer of 2022, however, I’ve been in Switzerland, continuing with my research into how to store radioactive waste. My scientific director in Ukraine had recommended me to apply for a Scholars-at-Risk fellowship. Specifically, it was for a position in the Nuclear Energy and Safety Research Division at the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI). I was delighted when they accepted me. It was initially with a one-year contract, though it’s since been extended twice. Thanks to Scholars at Risk, I was able to move into a peaceful flat in the countryside from the very first day. I love it!

“But I don’t find integrating easy. I miss my circle of friends a lot. Sometimes we meet for ‘dinner’ on a video call – but that’s scant consolation. Fortunately, many people here speak English, they’re keen to help, and take me climbing with them every now and then. I’m also learning German. But I have trouble expressing my feelings in a foreign language. I’m also pretty introverted. I mostly prefer to be alone within my own four walls.

“It’s difficult to lead a normal life when I get news every day about the Russian bombings and about the many civilian victims. But what I do appreciate is that my academic profile is benefitting from working here. And I know that I am making a contribution to the safety of the future deep geological repository for radioactive waste. So what happens next? I hope that I can stay for the long term – if society here has no objections. If they thought I wasn’t useful here, I couldn’t live with it”. kr

Parwiz Mosamim | Photo: Flavio Leone

“In Afghanistan, I would undoubtedly have been arrested”.

“After my bachelor’s in journalism and mass communication at home in Afghanistan, I took a master’s in public administration in Indonesia and at ETH Zurich. I then spent a few months in my hometown to see my family. That was early summer 2021, at the time when the Taliban were reclaiming power. Life became chaotic quickly. I had already been accepted for a PhD at USI in Lugano, so I left quite quickly. I wouldn’t have been able to work anyway, staying in my country. Worse, I would undoubtedly have been arrested and maybe imprisoned, given my experience as a journalist sometimes critical towards the Taliban.

“I’d wanted to study abroad so as to enjoy a quality education, gain experience and discover another culture. I had the financing for the first two years of the PhD, and I was supported by the Scholars-at-Risk programme for the third. This kind of programme is invaluably helpful. It opened doors for me. And I’m not just the only example: there are lots of restrictions on studying in Afghanistan, but there’s an entire generation that’s been trained who can carry on their studies in neighbouring countries, so long as they receive financial support.

“As part of my PhD, I work on the representation of Afghan women in public administration. I’m inspired obviously by what’s happening in my country. I want to show that it’s important to give a voice to women. From there on, I envisage continuing my research or joining an international organisation where I can, I hope, be useful to my country from near or far.

“In the meantime, I still have a year and a half of the PhD and I’m enjoying Switzerland, its nature and its food. I’m well looked after at USI and I feel well integrated. In return I help my compatriots integrate and I’m an ambassador of Afghan culture to my Swiss colleagues”. ef