INFECTIOUS DISEASES

After the pandemic is before the pandemic

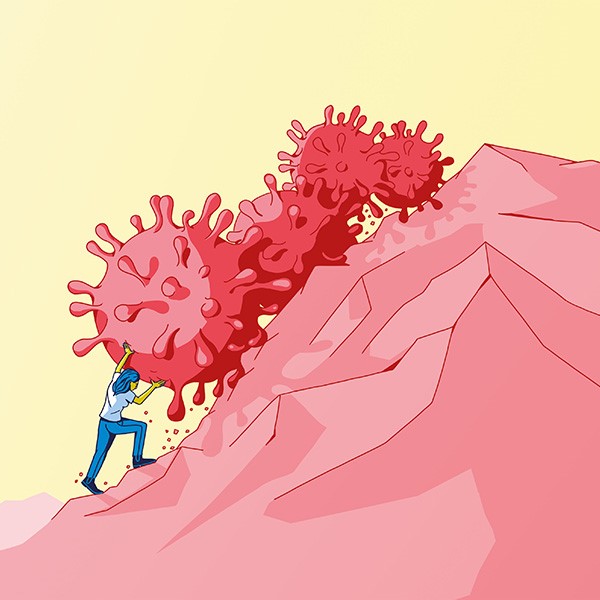

The world was ill-prepared for the coronavirus and how rapidly it spread. We consider how Switzerland might do a better job when the next pandemic arrives.

Will bird flu cause the next pandemic among humans? Scientists can’t predict anything, but they can get prepared for whatever comes next. | Photo: Keystone / Magnum Photos / Cristina de Middel

“It’s obvious that there’ll be another pandemic. The only question is how long we have till it happens”, says Kaspar Staub, a historian and epidemiologist at the Institute of Evolutionary Medicine of the University of Zurich. And there are signs that the intervals between pandemics are becoming shorter. Staub’s research topics include investigating past pandemics.

The next pathogen

‛Pathogen X’ is the name experts give to the as-yet unknown cause of the next pandemic. Besides well-known strains of influenza and coronaviruses, the possible candidates under discussion include lesser-known pathogens such as the hantavirus, which is widespread in mice. But it’s also possible that the next pandemic could be triggered by a completely new pathogen of which we have no knowledge at all.

Most experts agree that the next pandemic will probably be a zoonosis – a disease that jumps from animals to humans. It’s respiratory viruses with airborne transmission that pose the biggest danger – such as SARS-CoV-2 – rather than diseases that need skin contact to infect others, such as monkeypox. For several of these viruses, cases are being tracked and their genetic material sequenced in order to achieve timely recognition of mutations that can be a danger to humans. “But we don’t have the capacity to monitor every virus across the board”, says Silke Stertz, a virologist at the University of Zurich.

At present, it’s bird flu that’s at the top of the worry list. It’s already spread to cows in the United States, and some humans have also been infected there. But in this case, Stertz has given a preliminary all-clear because infection only seems to have occurred through close contact with cows and through being exposed to high doses of the virus. It hasn’t yet revealed any mutations that would enable transmission between humans. “But this doesn’t mean that the virus won’t adapt at some point to make this possible”.

His research shows that Switzerland has little trouble in generating attention and resources to combat a pandemic when it arrives. But things become more difficult the moment that the crisis is over. Experts call such an act of collective forgetfulness the ‘disaster gap’. Staub finds it understandable that people don’t want to live in a constant state of alert. “But this is precisely why we need to create a knowledge base and prepare the necessary resources now”. If we do that, then certain basics will already be in place whenever the next pandemic strikes.

The epidemiologist Nicola Low works at the Multidisciplinary Center for Infectious Diseases of the University of Bern. She and her team began preparing for the next pandemic even while the Covid-19 pandemic was raging. Significant gaps in knowledge became obvious at the time. “For example, we didn’t know how much contact people have with each other in everyday life in Switzerland”, she says. Such data are important when modelling the infection rate, for example. These models then provide a basis for taking decisions about what countermeasures are meaningful. Will compulsory mask-wearing help? And is it really necessary to close all schools?

One cohort is ready and waiting

“Without any baseline, we’re flying blind”, says Low. This is why, with support from the Vinetum Foundation in Switzerland, her team has initiated the only cohort study anywhere in Europe that’s focusing on pandemic preparedness. It’s called ‘Beready’. Their aim is to get 1,500 households across the canton of Bern to participate.

After an initial examination, the researchers will collect data using questionnaires on specific diseases and take annual blood samples. The participants will submit these samples themselves using fingerprick tests. This will enable the team to track how different infectious diseases spread within a family. They’re also including pets in their study, because pathogens often jump from animals to humans and vice versa.

What’s more, this Bern cohort is intended as a kind of rapid-response team in the event of another pandemic occurring. In such a case, the research team would already have a well-characterised group of participants that would enable them to identify important connections almost in real time – such as whether antibodies already present in the blood might protect participants against the new pathogen.

But it’s not just the human factors that we need to understand better. We still know too little about the pathogens themselves. In the case of the Covid-19 pandemic, for example, no one initially expected infected individuals to be contagious so long before showing any symptoms. This period is shorter in the case of influenza – and it was to fight influenza that the then extant Swiss pandemic plans were designed. SARS-CoV-2 also spread so swiftly because it proved unexpectedly effective at airborne transmission.

“Aerosol transmission is very difficult to contain”, says Silke Stertz, a virologist at the University of Zurich. “But our understanding of this process is still extremely limited”. This makes it difficult, she says, to develop effective countermeasures.

This is why, before the Covid-19 pandemic began, she was already working with a team from EPFL and ETH Zurich to develop a test system that generates infectious droplets and would allow them to investigate the processes that occur with an aerosol. For example, they wanted to see what effect the composition of the ambient air might have on the survival of a virus. “We hope that, once we’ve understood the principles, many avenues will open up for combating a virus”.

A quicker path to a vaccine

Employing the right countermeasures at the start of a pandemic can help to slow the rate at which it spreads. But the best way to stop it completely is vaccination. “In the case of SARS-CoV-2, it took 326 days from sequencing the virus to the first roll-out of the vaccine. That was incredibly fast”, says Aurélia Nguyen, Deputy CEO of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), an NGO based in Oslo.

If CEPI has its way, a vaccine should be ready just 100 days after the onset of the next pandemic. “This would save countless human lives and make a fundamental difference to the course of the disease”, says Nguyen. Their plan is ambitious, not least because no one knows what pathogen is going to trigger the next pandemic (see the box ‘The next pathogen’).

This is why CEPI is pursuing a broad-spectrum approach, using AI and other methods to try and identify the most dangerous virus families. It is also pushing for the development of vaccines against those viruses that we have already identified. “In the event of a pandemic, all you’d then need to do is insert the building block for the specific virus into the vaccine you’d already prepared”, says Nguyen.

Other measures CEPI proposes include preparing clinical trials, consulting regulatory authorities, and setting up vaccine production facilities around the world, also in the Global South.

“We’re not just relying on mRNA technology”, says Nguyen. It has many advantages, she says, such as rapid development and production, but it also has its limitations. It needs a continuous ultra cold chain, for example. And it’s possible that other types of vaccine could offer longer-lasting protection.

Nguyen also thinks that promising research is being undertaken into vaccines that could be effective against a large number of different virus families, including influenza and coronaviruses. Such ‘pan-vaccines’ might not always work optimally, but they can still be effective enough until a specific vaccine becomes available.

No longer just influenza

All such preparations are useful only if the measures in question are actually put into practice in the event of a pandemic. In what Nguyen believes is a positive step, the WHO this year adopted a Pandemic Agreement, according to which its member states must commit themselves to matters such as cooperating on supply chains and exchanging information. But nations still remain their sovereign right to take decisions on specific measures such as lockdowns.

Switzerland is also implementing the lessons learned from the recent pandemic. A revised national Pandemic Plan is due to be published in the near future. Anne Iten, the president of the Federal Commission for Pandemic Preparedness, has said in an interview that it’s going to be aimed at respiratory viruses in general, not just influenza (which, as mentioned above, was the focus of the previous Swiss Pandemic Plan). What’s more, this new Plan is going to be published digitally so that it can be updated much more quickly.

All the same, the extent to which new scientific findings will actually be incorporated into fighting the next pandemic remains unclear. “We can generate data, but ultimately it’s politicians who decide how to use them”, says Eva Maria Hodel, the project manager of Beready. This is why her team is setting up the necessary contacts and is already engaged in a dialogue with decision-makers.