The politics of migration

Growing up in a cupboard

In the second half of the 20th century, Switzerland wouldn’t allow seasonal workers from abroad to bring their kids with them. This affected some half a million children. Salvatore Bevilacqua is a social anthropologist who’s researching into the psychological and social consequences that still reverberate today.

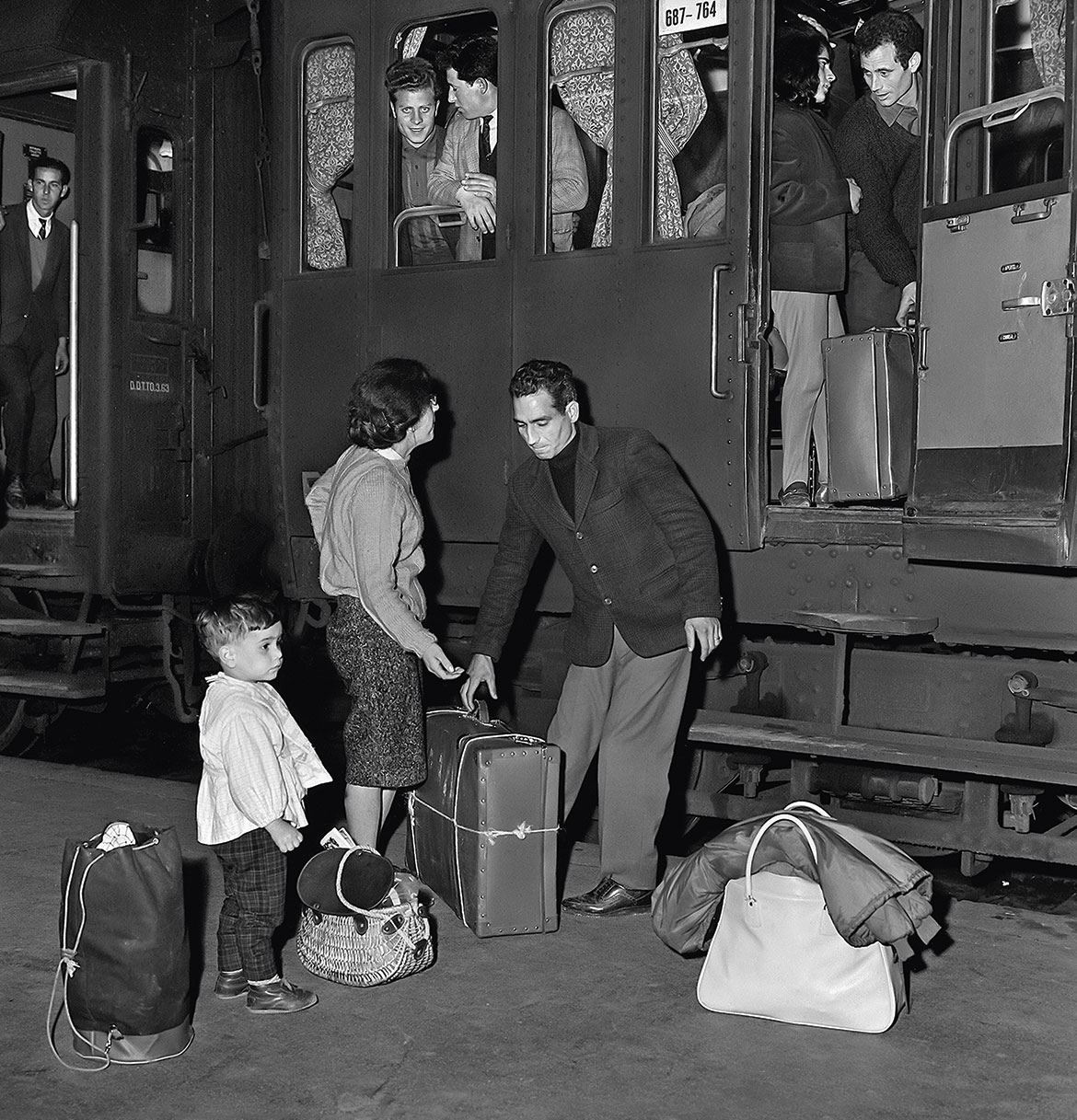

Italian migrant workers in 1963, boarding a special train at Zurich’s main station that will take them back to their home country so they can vote in elections. | Photo: Keystone / Photopress-Archiv

The fate of indentured orphan children (the ‘Verdingkinder’) became a major topic of debate in Switzerland not many years ago. Are the so-called ‘Schrankkinder’ of Switzerland – literally ‘children in the cupboard’ – also now becoming a political issue? The term is used by both the media and researchers to refer to the estimated 500,000 children who were prevented from entering Switzerland in the second half of the 20th century – in varying proportions from Italy, Spain, Portugal, Yugoslavia and Turkey – even though their parents were employed here.

The Swiss seasonal worker statutes in force at the time prohibited those with a temporary work permit from bringing their relatives with them.

The primary victims of this policy were their children. Some were smuggled into the country anyway and then hidden in cupboards or under the bed by their parents. But most of them stayed with grandparents in their country of origin or in children’s homes near the Swiss border, or sometimes even with foster families in Switzerland.

The sociologists Toni Ricciardi and Sandro Cattacin from Geneva were among the first researchers to investigate this topic and to make numerical estimates. They reckon that some 50,000 children of so-called ‘guest workers’ lived in Switzerland illegally between 1949 and 1975. They were not allowed to be noticed – a fact that their parents impressed on them – and many of them neither went to school nor even went to see a doctor if they were ill.

Sibling rifts

“This resulted in a traumatic childhood for almost everyone involved. They lived with the constant feeling of being illegitimate. And that feeling has stayed with them to this day”, says Salvatore Bevilacqua, a social anthropologist at the University of Lausanne. He has interviewed some 30 affected people whose parents came to Switzerland from Italy, Portugal or Spain. Many of them initially just erased their childhood from their mind – “they don’t want to remember the painful things that happened – or can’t let themselves remember”.

There have also been intergenerational rifts and rifts between siblings. The life paths of brothers and sisters sometimes went in different directions, which is perceived as unfair by the interviewees. They ask questions such as: “Why was my sister allowed to stay with our grandmother, and why did our parents place me in a home instead?”.

Bevilacqua says that this fragmentation of memory, together with ruptures within families, can ultimately lead to identity trauma. These experiences could also have had a negative impact on childhood development “because those children had too little contact with other children, or felt that they had to be hidden away because they were bad”. Many of those affected continue to suffer to this day from the damage done to them.

But aren’t almost all families marked by things that remain unsaid, by rifts, taboos and tears? “That’s true”, says Bevilacqua, “but the temporary residence permits given to seasonal workers meant that their families were simply not accepted. Behind their status lay a form of administrative violence that usually went hand in hand with economic uncertainty”.

The authorities should apologise

Bevilacqua believes that his conversations had a “cathartic effect” on many of those whom he interviewed. That in turn can lead to those affected getting involved in issues of migration policy – just like Bevilacqua himself, who grew up in Italy while his parents worked in Switzerland.

He and other victims are active today in TESORO, the ‘Association for addressing the suffering of illegalized migrant families with seasonal and annual residence status’. They are demanding, for example, that the authorities apologise, identify those responsible for the injustices committed, and ensure that those injustices are never repeated.

Sandro Cattacin is convinced that the topic of the ‘cupboard children’ will assume similar socio-political dimensions to the ‘Verdingkinder’: “We are faced with yet another dark chapter in history that needs to be illuminated”. He suspects that the authorities will soon have to get involved.

This chapter isn’t over yet. The hurdles for family reunification still remain high. A motion was recently passed in the Swiss National Council that would prevent people temporarily admitted to Switzerland from bringing their families with them. It only narrowly failed to pass in the Council of States. It’s almost as if the consequences of the seasonal worker statutes had gone completely unnoticed.