Feature: From images to knowledge

Seeing clearly now

When researchers need the right image to answer a question, these three people can help: an archivist, a microscopy specialist and an information scientist.

Photo: Lucas Ziegler

Finding ‘gold’ in tissue

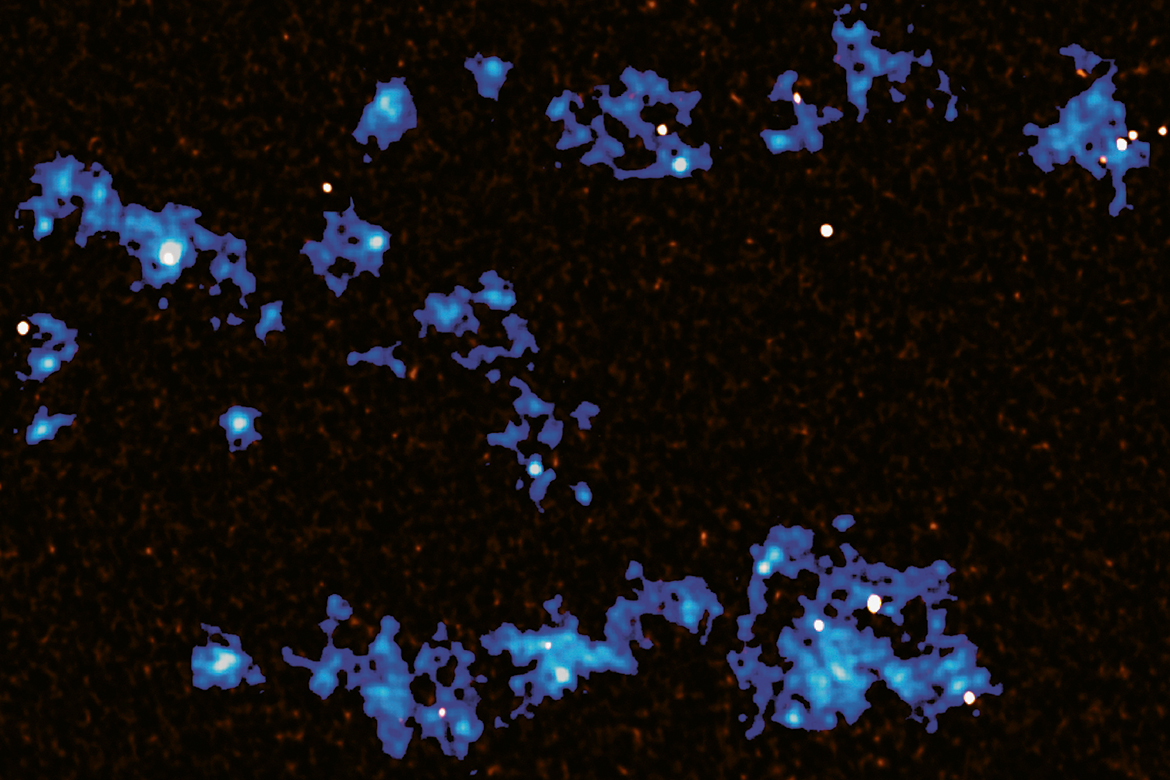

The daily routine of Anjalie Schlaeppi is basically focused on the lab and her support for scientists. She specialises in ‘spatial omics’, or the art of creating and analysing microscopy images combining tissues and cells with molecules of interest. This discipline includes techniques that allow scientists, for example, to locate proteins in brain tissues or to know which genes are active in which cells of a tumour.

Schlaeppi is an energetic young woman who emphasises that her role within the platforms ‘BioImaging and Optics’ and ‘Histology’ represents “the first multiplatform position in the life sciences” at EPFL. Indeed, spatial omics, which has been taking off in recent years, requires an interdisciplinary approach. “I rely on my colleagues who prepare samples, assist researchers, maintain equipment, manage data and analyse images”, she says, admiring the dexterity of the people experienced in certain tasks such as histological sectioning.

“Scientists are interested in the spatial organisation of three types of molecules: proteins, DNA and RNA. It’s magical to see how cells are structured!”, says Schlaeppi, full of passion for the subject. The tissues examined under the microscope are either human or animal. “The analysis of the zebrafish embryo struck me! It was fascinating to see how structure and function come together in a developing organism”. It’s worth noting that spatial omics allows the observation of several thousand molecules at the same time. It is up to analysts to play ‘gold panners’.

In addition to EPFL, the two platforms respond to the requests of other universities and start-ups. “Scientists need support over the four to eight months that the projects last”, says Schlaeppi. “Based on their samples, they have very specific questions that we help them answer”. Even if this technology is becoming widely available, it’s still expensive, each experiment costing many tens of thousands of francs and often requiring additional fundraising. The space omics service has been gradually rolled out over the past three years. Since 2024 it has contributed to 17 projects, three of which have been completed, and it is currently studying about twenty files.

On a more personal note, Schlaeppi talks about her relationship to aesthetics and the philosophical dimension of visuals, despite the dramatic aspect of some analytical cases, e.g., tumours: “I appreciate drawing, art, poetry in the samples. If researchers authorise it, I like to share certain images of tissues on social networks for their beauty, which could be compared to corals”.

Photo: Lucas Ziegler

Guardian of a galaxy of 1.8 million images

There’s a photograph in Beat Scherrer’s office at the Swiss National Library in Bern that dates from the early 20th century and shows two women from the Upper Goms region of the canton of Valais: one holding a pitchfork, the other a scythe. “Many more of Switzerland’s Alpine landscapes back then were devoted to agriculture, and at the same time they were far more untouched”, says Scherrer. This photo is one of his favourites – and it’s one of just 1.8 million images for which he is responsible. Scherrer is a research assistant in the Prints and Drawings Department that holds not just photographs, but also postcards, prints, posters, artists’ books, architectural plans and documents on the preservation of historical monuments.

He sums up the mission of his collection as follows: “We preserve images of Switzerland. In other words, what did Switzerland and its people look like in the past, and what do they look like today? How have they changed?” This isn’t just interesting to historians, but also to sociologists, artists, filmmakers, architects and private individuals.

“Every one of them comes with a different question. That’s what makes my job interesting”. For example, a historian might be writing a book about the development of cottage industries in Switzerland. Scherrer can help them to find the right pictures. “It can be highly challenging because there isn’t simply a box here labelled ‘cottage industries’ or ‘working from home’”. To be sure, there’s a database that an interested party can search on their own, but by no means all of the Department’s collection has been catalogued. “Many holdings are simply stored in boxes, folders and drawers. But there are index cards, and I also have a rough idea in my head of where everything is stored. With this knowledge, I can help people with their searches”.

His department is constantly adding new material to its collection. “We try to collect as many advertising, political and tourism posters as possible. They may not be particularly interesting to today’s visitors, but things will be different, 50 years from now”. Collecting is like planting an apple tree. You don’t do it for yourself, but for future generations. All the same, this doesn’t mean his department accepts everything. “We’re offered lots and lots of material, so we have to make a selection. We want to achieve a broad cross-section that should cover as many Swiss regions as possible, for example”.

Scherrer describes himself as a ‘lateral entrant’ to the career of a librarian. “I used to be a landscape architect. My work meant doing a lot of research in libraries and archives. That’s how I got a taste for this”. He did postgraduate studies in information science and ended up here at the National Library some eight years ago. “I’m more of a visual person. Images stick in my mind, whereas I’m not so good at remembering texts. I can’t remember a single quote by Goethe. But I know exactly which folder contains the photo of the two women from Obergoms”.

Photo: Lucas Ziegler

Drawing with algorithms

“Regrettably, I’m no good at painting”, says Renato Pajarola, as he gazes at the landscape paintings by his mother that hang in his office. That might well be true when it comes to working with brushes and paint. But this professor of computer science at the University of Zurich can generate impressive images using numbers and algorithms. Pajarola is head of his university’s Visualization and Multimedia Lab. His research projects cover a broad spectrum of topics, though they’re all about making abstract data comprehensible. “We often say that a picture is worth more than 1,000 words. I agree. Our visual perception as human beings is much quicker than our ability to engage in abstract thought”.

One example of how Pajarola uses his skills for research purposes is how he goes about depicting data from computer tomography. “This involves very large amounts of data, and we try to present them more quickly”. This not only helps with medical diagnoses, but is also useful to archaeologists when examining mummies, for example. Pajarola’s algorithms are also used to visualise weather and climate simulations.

Sometimes, he even gets involved in unusual projects such as his collaboration with EPFL and the Montreux Jazz Digital Project. “They’ve digitised 40,000 videos and songs and would like to make them available to the public in a new, interactive way. The question we were faced with was this: How can we help users to navigate this jungle of images and sound efficiently?”.

Despite these many collaborations, Pajarola doesn’t see himself as a service provider whose task is to do what industry wants of him. “In many areas, research is ahead of industry”, he says. “One example is architecture, where we’re researching into how we might improve visualising and reconstructing existing buildings. We’re sounding things out. We’re looking at what’s feasible. But this also means that many of our programmes are not yet robust enough for widespread application. Our doctoral students aren’t given the direct goal of making a product ready for the market. Their primary aim is to explore new things and to publish their findings”.

Pajarola’s research basically requires just a good computer. In recent years, standard consumer devices have become so powerful that you can do almost anything with them. “It’s only when the data volumes get really large that we need better processors and graphics cards. And they can easily cost a few thousand francs”.

Pajarola owes his career to the algorithm of life. “I never planned my career, but I was lucky at the right moment and made the right decisions”. He had always wanted to do research and to implement his own ideas. “I could also have gone into industry. But instead, I was given the opportunity to build up a research group – to do something new that didn’t yet exist”.