AVALANCHE RESEARCH

How far the snow falls

Models are calculating when avalanche warnings require mountain roads to be closed.

Back in 2019, this avalanche in the Dischma valley near Davos reached the main road. | Photo: Vali Meier

When there’s a risk of an avalanche, should roads be closed or left open? Those who have to decide these trade-offs between safety and cost-effectiveness often rely on a lot of experience, though ultimately it’s a gut decision. Julia Glaus of the Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research in Davos is now trying to use measurements and simulation tools to provide decision-makers with a data-based tool instead.

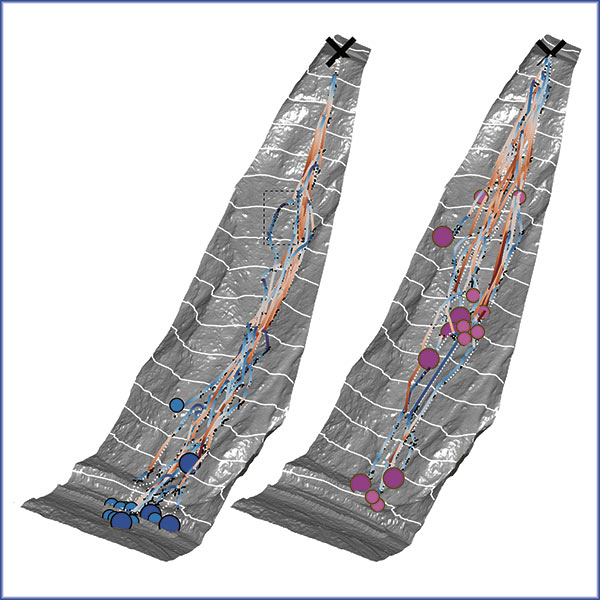

To this end, she is using a network of measuring devices around Davos whose data is fed into models. She is thereby able to simulate the dynamics of an avalanche and create a risk assessment, almost in real time. “These models are simple, and if you’re working with a single possible avalanche, you can even run them on a mobile phone”, says Glaus. She tested her model during avalanche blasts in the Dischma valley.

However, the prospects for expanding the application of her system are limited, because it requires installing measuring devices to record the most important avalanche parameters: the depth of new snow, the snow temperature and – a very important factor – the wind. When it has sufficient measuring points – several in the valley and several on the mountain itself – then the model shows which sections of road could be buried by an avalanche.

Climate change is making snowfall less predictable. So using only the experience gained in the last 50 years will no longer work when we want to predict avalanches today. This makes it all the more important to use data-supported models that can keep up with changes in the climate. “We are moving forward step by step and are examining how well our methods might be applied to other valleys, regions and cantons”, says Glaus.