YOUNG OPINIONS

“Efforts to bridge science, policy making and the economy are not valued”

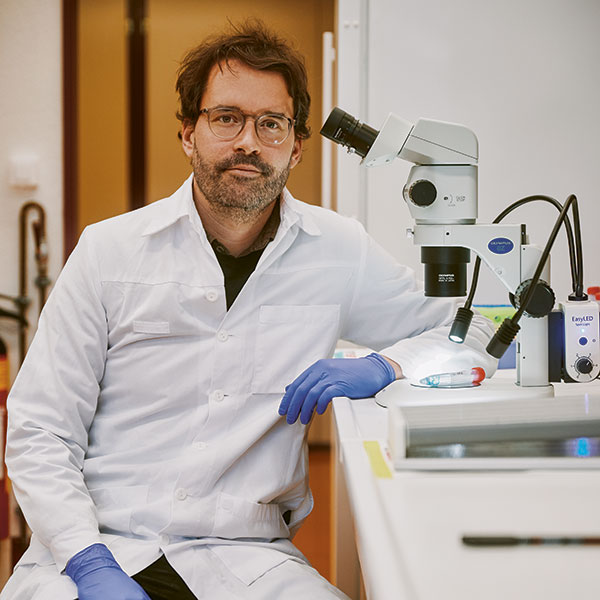

Abishek S. Narayan is researching into water management at Eawag and would like to see greater recognition of the work being carried out at the interface between science and society.

Abishek S. Narayan is a water management researcher at Eawag in Dübendorf. He is a member of the Swiss Young Academy. | Illustration: Klub Galopp

A growing number of young researchers, including me, are drawn to bridge the divide between science and policy. We remain convinced that pursuing science for its own sake is essential, but are also motivated by the belief that our research can and should shape real-world outcomes. Switzerland is a hub for science diplomacy, multilateral policy making and multinational companies, so it naturally attracts the right talent. Institutions like CERN, the Geneva Science-Policy Interface, Geneva Science and Diplomacy Anticipator (GESDA) and Swissnex are helping to create international networks in education, research and innovation – a unique ecosystem. An influx of global young talent helps Switzerland to remain at the cutting edge of innovation.

Yet these young researchers are finding limited opportunities at the interface of science and society. Despite high-level institutional strategies emphasising the importance of bridging the gap between them, opportunities for meaningful involvement are few and far between, and jobs in this field are similarly rare. Contributions from researchers in this field are not actively recognised in academic appraisals and are undervalued in terms of career advancement. Efforts to connect science with policy making or the economy are often viewed as merely ‘nice to have’. Yet bridging this divide should no longer be the icing on the cake, but the cake itself.

Switzerland, as a whole, would benefit from specific funding dedicated to transferring scientific knowledge to civil society, politics and the economy. Success in this field should be honoured with specific awards, while applications for grants or academic jobs should be evaluated from a holistic standpoint. When young researchers leave academia seeking roles that bridge science, policy and practice, they find few such jobs available. Academic institutions should do more by creating dedicated roles such as knowledge brokers, science-policy champions, technology-transfer specialists and leaders for transdisciplinary projects, instead of expecting these tasks to be absorbed into the traditional roles of researchers.