Science journalism

From cheerleader to watchdog

From cheers and jubilation to well-informed scepticism, the role of science journalism has shifted over the past decades. We take a look at some historic milestones.

Science journalists write mostly for popular magazines such as New Scientist and for the science pages of national media outlets. They write less often on broader topics such as politics or economics. | Photo: provided by subject

Science journalism in the West was given its first real boost by the Soviet satellites Sputnik 1 and 2. They were the first of their kind – and, along with the rockets that carried them into space, they triggered social shockwaves in the USA. They also helped to fuel the subsequent US space programme.

When American rockets first lifted off at Cape Canaveral, they also launched the careers of science journalists such as Mary Bubb, the first-ever woman in her profession. To this day, she and several other science journalists are honoured by NASA under the name of ‘the Chroniclers’.

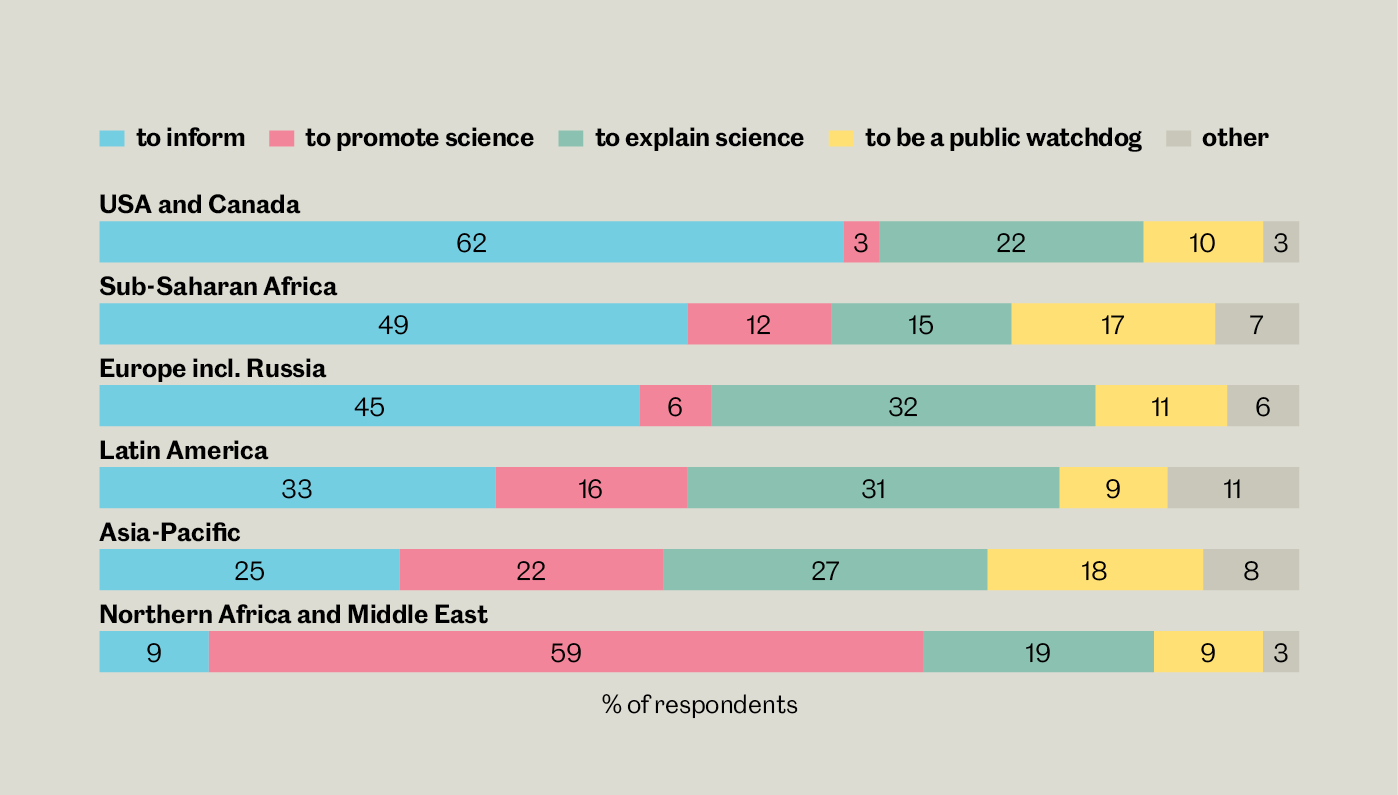

The role of science journalists

To inform, to explain science and to promote it – these are the three tasks that science journalists feel best define their role. | Source: Global Science Journalism Report 2022

Thus dawned the golden age of the science cheerleaders. “The mood amongst those reporting on technological developments in the post-Sputnik era was generally enthusiastic. Admiration and awe were typical of science journalism for a long time”, says the Brazilian communication scientist Luisa Massarani in an article about the World Federation of Science Journalists (WFSJ) that she has authored together with several colleagues.

From the 1960s onwards, however, that enthusiasm was increasingly matched by scepticism. In her book ‘Silent spring’, published in 1962, the biologist Rachel Carson documented the ecological damage wrought by pesticides. This marked the beginning of the environmental movement that played a key role in bringing science journalism back down to earth to be confronted by dirty facts.

of 505 science journalists consulted across the world confirmed that they work freelance.

is the average age of science journalists across the world.

of science journalists consulted across the world regard low pay as the biggest hurdle in their reporting.

of those consulted would recommend a career in science journalism to students.

According to Holger Wormer, a German expert in science journalism, the environmental disasters of the 1980s merely served to hone the critical faculties of the science press, whether they were reporting on acid rain in Europe, the chemical disaster of Bhopal in India or the nuclear accident in the Chernobyl reactor. Massarani and her team also write that “those journalists were concerned less with scientific developments than with the consequences for the Earth of our modern technologies”.

The turn of the millennium brought ethical debates about stem cell research, cloning, and the Human Genome Project. This was another milestone in journalism on science and its impact on society. In Wormer’s words: “Back then, science journalism became more dominant, and people thought that this would result in new, long-term structures in editorial offices. But then came 9/11”. That placed very different issues centre-stage.

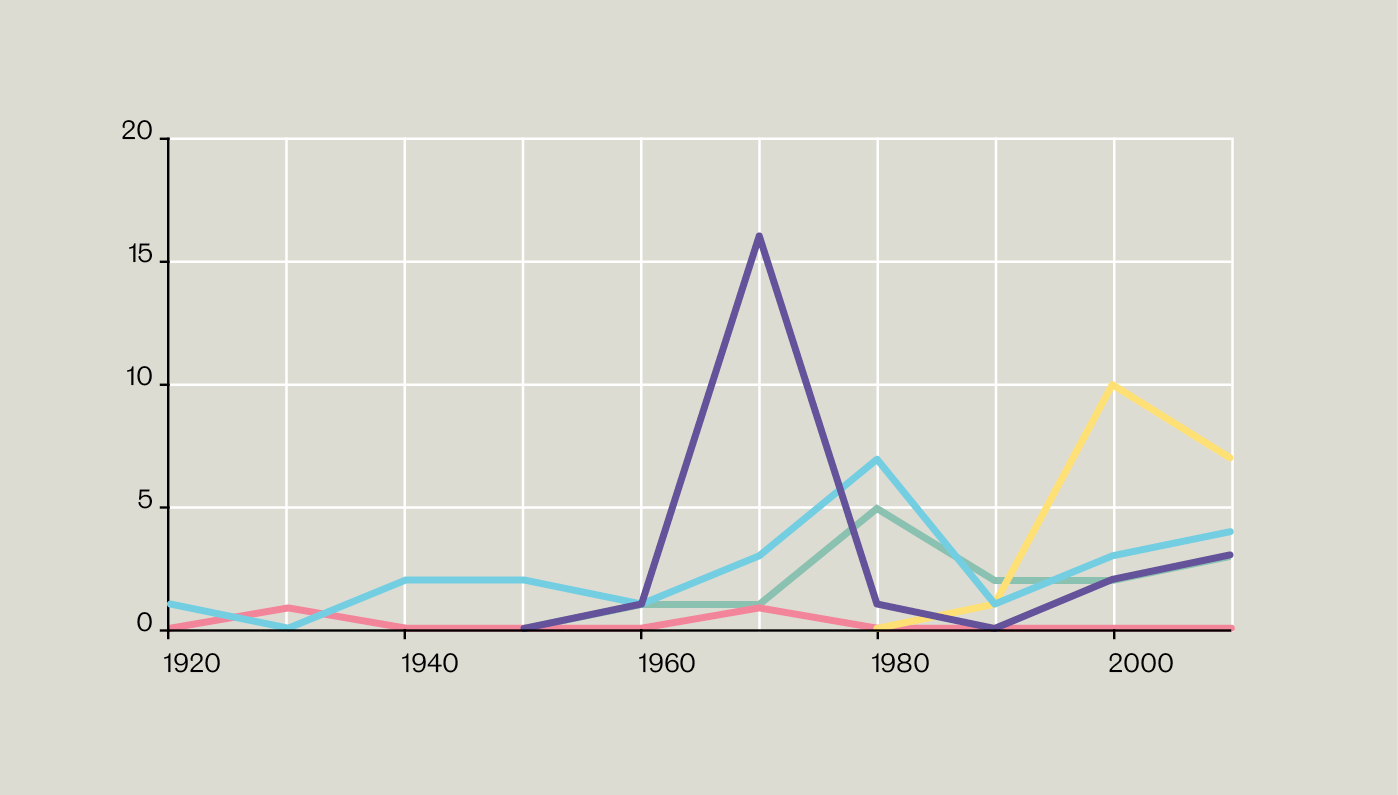

National associations set up

In around 1970, Latin America saw a spike in the number of national associations founded, whereas Europe saw a peak only in circa 1980. In Africa, the upward trend began in the 2000s, which was also when the World Federation of Science Journalists was founded. | Source: Compiled by Massarani, Magalhães and Lewenstein (2025) with data from Gascoigne et al. (2020), Massarani and Magalhães (2024), White (2007) and the websites of the associations.

During the Covid pandemic, between 2020 and 2022, Wormer felt a sense of déjà-vu. Science journalism was once more the measure of all things. “But its increased importance was temporary and didn’t last”, he says. In concrete terms, it means that hardly any new, fixed structures emerged in editorial offices.

“When journalists in the newsroom report on the controversial US data analysis company Palantir, for example, they ought to consult colleagues on their science staff as a matter of course. But there are many places where that still doesn’t happen”, says Wormer. What’s more, “political newsrooms are once again chasing day-to-day issues and are primarily interested in what the US president has just said”.

Good ideas from Latin America

The 13th World Conference of Science Journalists has just ended in Pretoria in South Africa. The very first such conference was held in Japan in 1992. And it was the third conference, held in Sao Paolo in Brazil back in 2002, that led to the founding of the World Federation of Science Journalists (WFSJ) that now comprises some 70 national associations. The Brazilian communication scientist Luisa Massarani and her colleagues have been analysing the development of the WFSJ. “These professional associations have played a key role in consolidating science journalism”, she says.

Three supra-regional associations have been crucial in the history of the WFSJ: the International Science Writers Association (ISWA), which began as a largely Anglo-American-Canadian grouping; the European Union of Science Journalists’ Associations (EUSJA); and the Ibero-American Association of Science Journalism (AIPC) that was founded by Spanish and Venezuelan science journalists in 1969. Massarani and her colleagues describe these three associations as the predecessors of global science journalism: “Setting up the AIPC was the first step towards the WFSJ”. In the 1970s, the AIPC fostered the founding of national associations in Latin America. In Europe, the EUSJA was formed by joining together existing national associations. It experienced an expansion from the 1980s onwards when the Soviet Union broke up. One of the WFSJ’s aims was also to promote local associations in Africa, and their efforts were rewarded with success when the number of such organisations being set up reached a peak after 2000.

All the same, Massarani and her team have found that science journalism in the Global South remains dependent on other countries. This in turn limits the critical perspective of their reporting. The WFSJ accordingly wants to continue bringing together science journalists from all over the world, as this can help to reduce the gap between the West and the South.

In a paper published back in 1989, Walter Hömberg referred to science journalism as ‘The belated department’. And it still hasn’t progressed to a point where it can stand securely on its own two feet. Today, both journalism and science itself are suffering from a lack of certainty when it comes to funding. “This isn’t going to get any better in the age of AI”, says Wormer.

There’s another worrying development right now. Research institutions themselves are communicating more and more. “You could be forgiven for thinking that the universities could simply carry out science reporting on their own”, says Wormer. “But what they communicate is dominated by what’s good for their reputation. Above all, they want to prove to the world that they’re doing something really great”.

Wormer wonders “why is there hardly any real, solid science communication that respects scientific and journalistic standards? In my case, when I write a scientific article, I also have to discuss the limitations of the research results, the literature of other researchers, and the contradictions between them”.

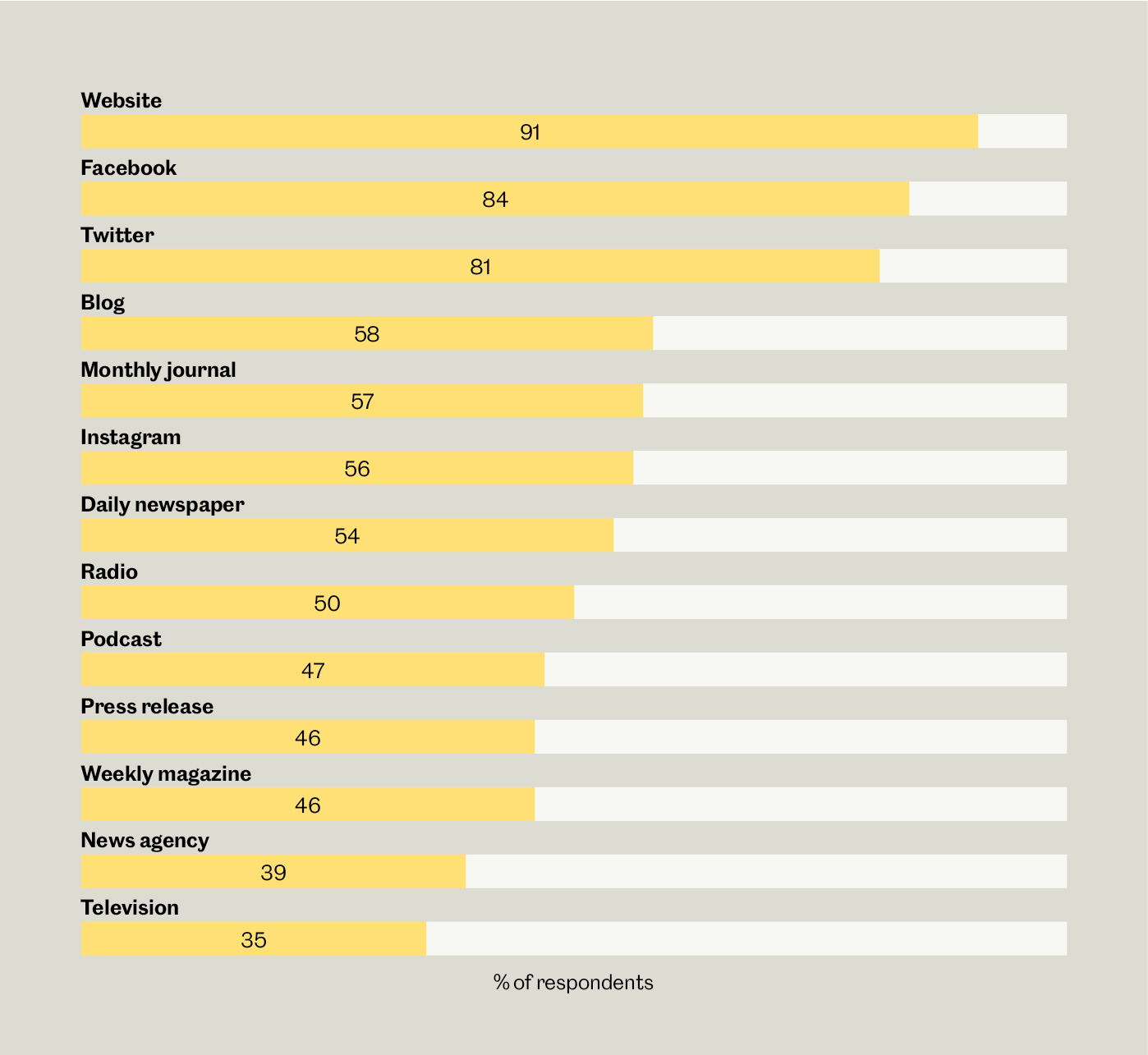

Where stories are published

The Internet is the most important medium for disseminating the work of science journalists. | Source: Global Science Journalism Report 2021

Wormer is convinced that this is now more necessary than ever before: “A department of communication can no longer say to itself: ‘We can blow our own trumpet because the journalists will put it all properly into context’. No they won’t, because the end users will simply read the press release itself on the Internet. So what they announce has to be contextualised right from the start”. But Wormer also sees an opportunity here: “Science journalists ought to worry less about their duty to chronicle what’s being done and write less about individual new studies. Then they could spend more time putting things into context”.

If science journalists followed Wormer’s advice, they could focus more on their role explaining the connections between research findings and their consequences for society. And they could function as the watchdogs of the science system. Gone are the days of cheerleaders who simply looked up at the sky with enthusiasm.