Researchers in the dock

Time and again, scientists and scholars have to appear in court – and occasionally it’s them under investigation. Sometimes they’re the plaintiffs, at other times they’re the defendants. Some of these cases are simply bizarre, but others give us food for thought. We offer a selection of them here.

Illustration: Christoph Frei

Deadly reassurance

Scientists in the dock

2012 / L’Aquila (I) / Government v. geologists

In 2012 manslaughter charges were brought for the false reassurances that had left 300 dead at L’Aquila. First instance: guilty. Second instance, two years later: acquitted.

How on earth could scientists be convicted for failing to predict an earthquake? That was what many demanded to know in 2012 after seven scientists were convicted of manslaughter and handed down six-year jail sentences for the advice they had given ahead of the deadly L’Aquila earthquake of 2009.

In fact, the case against the seven experts, including seismologist Enzo Boschi (see Q&A), was quite different. They took part in a meeting of an official government advisory committee in L’Aquila a few days before the magnitude-6.3 quake, after several months of small and medium-sized tremors that had left residents on edge. The experts were convicted for false reassurances that led some of the 309 people killed in the quake to stay indoors rather than to seek safety outside, as had been their custom until then.

All but one of the seven were acquitted on appeal in 2014, and then by Italy’s Supreme Court a year later. Only the two-year jail term for the civil protection official Bernardo De Bernardinis was upheld. He had wrongly told the public that the on-going tremors posed “no danger” because they discharged energy, and so made a major quake less likely.

Commentators had in fact already criticised handing down the same sentences for all the defendants. One of these critics was Max Wyss, then director of the World Agency of Planetary Monitoring and Earthquake Risk in Geneva. Wyss pointed out in an article that De Bernardinis in fact made his reassuring comments ahead of the experts’ meeting.

The appeal judges ruled that the experts had no reason to think that the smaller tremors made a big quake more likely, but others have been more critical. Francesco Mulargia, a seismologist at the University of Bologna, points out that the probability of a large event can then rise at least a hundredfold.

According to Anna Scolobig, a social scientist at ETH Zurich, the L’Aquila case highlights the complexity and delicacy of a science advisor’s job. Experts, she says, face both scientific uncertainties and a lack of clarity about how far they should go in suggesting courses of action – a problem accentuated at L’Aquila, she argues, by what she describes as the “mandate” given to the seven by the civil protection authorities to reassure the public.

However, what appears fairly clear, says Scolobig, is that advisors and civil authorities in future will be at ever greater legal risk. She argues they are therefore likely to issue more false alarms and in the longer term perhaps take out insurance. But by doing so, she warns, “they may not be doing what is needed to defend vulnerable communities”. ec

Image: Keystone/ANSA/Guido Montani

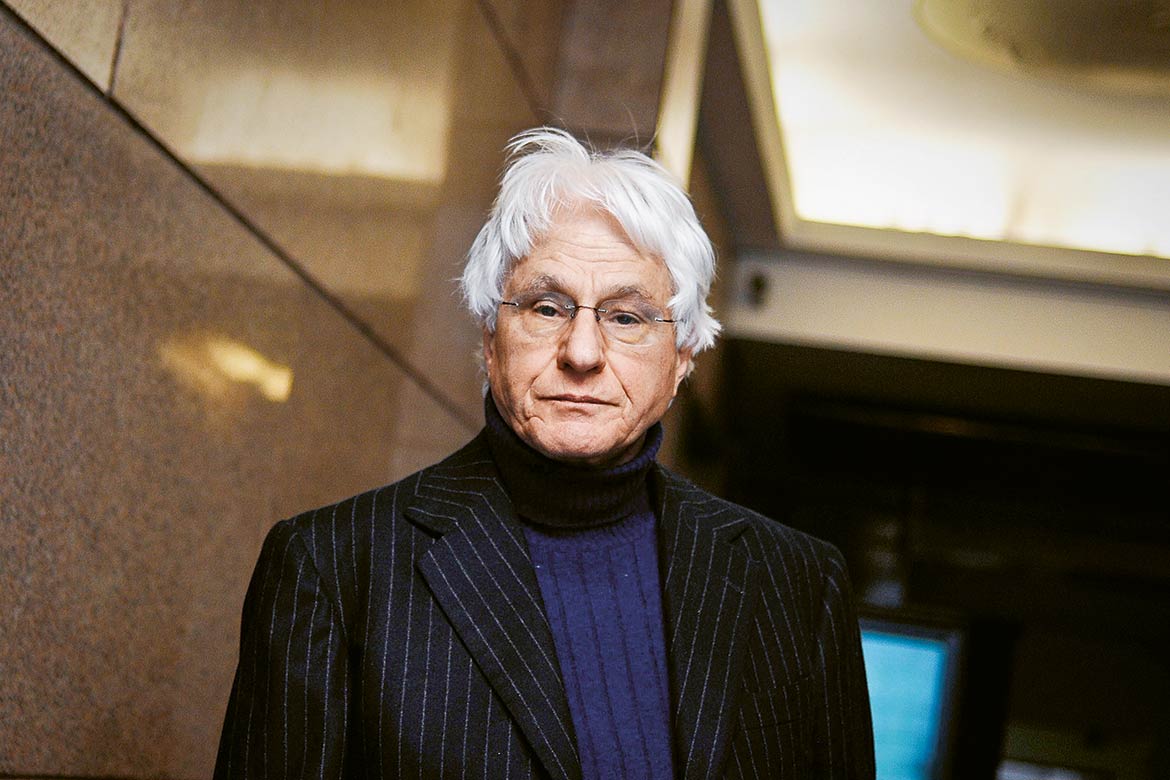

“I have never reassured anyone”

Enzo Boschi, who was president of Italy’s National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology in 2009, recalls his experience of the trial.

Q: How did you feel when told of your prosecution?

A: It was depressing. I had thought the investigations would be over quickly as I couldn’t imagine what I had done wrong.

Q: What was the trial like?

A: I wasn’t able to sleep; I had nightmares. I was convinced I was going to be acquitted. But then I was convicted, and that was dramatic.

Q: How did other scientists react to your conviction?

A: They gave me great support. They all thought the trial was completely absurd. I also got informal offers of political asylum and work from four or five countries.

Q: Could it ever be right to put scientists on trial?

A: Yes, if you know something and don’t say it, or you change it. If a politician asks “Is that area dangerous?” and you say “No”, that is illegal. But if you make a mistake in good faith, then it’s not.

Q: Would it have been a crime to reassure people if ordered to do so?

A: Yes, absolutely. But I only spoke with the boss of civil protection after the earthquake. In contrast, one of the other defendants talked with him after the meeting and said that everything had gone as planned.

Q: If you could go back in time, would you do anything differently?

A: No, I would do exactly the same. During the trial, people in L’Aquila thought we were incompetents and criminals who had only come to reassure people they were safe. But that is absurd because I never reassured anyone.

ec

Illustration: Christoph Frei

History as censorship

Proving the obvious

2000 / Holocaust denier vs historian

“Some things are true. Elvis is dead, the icecaps are melting and the Holocaust really happened”, says Deborah Lipstadt in her lectures. This American historian researches into Holocaust deniers such as David Irving from the UK, who has described Auschwitz as a mere tourist attraction. Irving was offended at his depiction in Lipstadt’s book Denying the Holocaust, and so took the historian and her publisher, Penguin Books, to court for libel, defamation and business damages. He did this in London because the burden of proof there lay on the defendant, not on the plaintiff as in the USA. History has to be able to be debated, he insisted.

So Lipstadt had to prove that the Holocaust was not ‘debatable’, but so evidently factual that a historian cannot deny it. In an unprecedented feat, five renowned scholars prepared for Lipstadt’s defence. One of them was Richard Evans, a professor of modern history at Cambridge, who presented a 740-page report of his own that was the result of 18 months of research. The judge was convinced, and dismissed Irving’s case on 11 April 2000. No restrictions were placed on further sales of Lipstadt’s book, and the author was free to name Irving as a Holocaust denier, an anti-Semite, and a racist.

“Good scholarship needs open, critical discussion” insists Stephanie Mathisen, the policy manager of the independent British lobby group ‘Sense about Science’. It is thanks to them that a libel action like Irving’s would no longer be possible in Great Britain. In June 2009, the group started the campaign ‘Keep libel laws out of science’. They were successful, the result being the Defamation Act of 2013 that prevents such legal action from being taken against publications that are on matters of public interest. These ‘matters’ include science and medicine.

“If anyone today wants to sue scientists for defamation just because they have engaged in well-founded criticism, they will automatically be outed as a pseudo-scientist and a charlatan”, says the Viennese biologist Erich Eder. Back in 2004, he too found himself in court charged with defamation, reputational damage and errors of omission after publishing a letter complaining about the ‘revitalised water’ marketed by the Grander company. He had written that their claims to its healing powers were “pseudo-scientific humbug”. However obvious it might seem to a scientist that everyday water can’t possess any supernatural qualities, it was only on appeal that the judge decided in his favour. af

Illustration: Christoph Frei

Patent dispute

Whodunnit first?

2017 / The CRISPR case: Researchers vs researchers

It’s regarded as a revolution in genetic engineering: the CRISPR method opens up the possibility of altering genetic material quickly and precisely. The discovery of these ‘gene scissors’ was announced in 2012 by researchers from the University of California, Berkeley.

But their publication was followed by a dispute lasting several years about the rights to the patent. Because shortly afterwards, researchers at the Broad Institute in Massachusetts succeeded in using the CRISPR method in human cells, for which they were themselves awarded a patent. The University of California filed a complaint, claiming that transferring the ‘gene scissors’ to human cells was not an independent invention – though the US patent court disagreed with them, and so dismissed their objection in February 2017.

This patent dispute shows the immense economic relevance of the CRISPR method. Instead of concentrating on the scientific and societal consequences of the procedure, much energy was invested in determining who has the right to its commercial use.

Do such disputes about patents actually damage science? Nikolaus Thumm, the former chief economist of the European Patent Office, is not so sure: “In such cases, it’s not usually the scientists themselves who are arguing, but the technology transfer offices of their respective universities who are responsible for patents”. These offices display a market orientation that is in every way comparable to the private sector. “Research itself is usually untouched by all that”.

But Thumm wonders just to what degree research today should really be oriented to commercial use: “These issues can’t be answered solely from the perspective of patent law”. However, if research institutions want to profit from their inventions, there is currently hardly any alternative to filing for a patent. jr

Illustration: Christoph Frei

Monkey puzzles

Waiting for 43 months

2017 / Animal-rights activists vs neuroscientists

Valerio Mante works at the Institute of Neuroinformatics of the University of Zurich and ETH Zurich. His wants to improve our understanding of mental illnesses such as schizophrenia – but he had to wait three-and-a-half years for permission to carry out an experiment with three Rhesus monkeys. He filed an application with the cantonal veterinary office on 1 October 2013. It was subsequently approved, but the three animal rights representatives on the cantonal animal protection commission filed an appeal. The cantonal government needed 18 months before they could give the green light again. A second appeal came before the administrative court of the canton, which took another year. It was only in April 2017, 43 months after filing the application, that Mante was able to begin his research. “The decision of the administrative court is now incontestable”. af

Illustration: Christoph Frei

Apocalypse later?

Putting a legal brake on the end of days

2010 / Amateur physicists v. Cern

In 2008, a complaint was filed at the European Court of Human Rights with the aim of stopping the hunt for the Higgs-Boson in CERN’s LHC particle accelerator. The plaintiffs’ argument was that the procedure could result in the creation of tiny black holes; and if these were to swallow up the Earth, it would mean that a few particle physicists had deprived the whole population of the world of their right to life.

These objections were swiftly dismissed in August 2008, and the complaint itself was declared inadmissible by a single judge in 2010. Similar complaints were filed in the USA and at the German Federal Constitutional Court, but were similarly rejected for being “insufficiently substantiated”.

These cases pose an immense challenge to our legal system. Apart from forcing our courts to cope with highly complex questions of physics, it also means they have to evaluate a hypothetical risk in which nothing less is at stake than the life of the world as we know it. Eric E. Johnson is an assistant professor of law at the University of North Dakota, and he puts it all in perspective: “It’s not the task of the courts to pursue scientific enquiry in such cases”. The credibility of the arguments on both sides can in fact be judged appropriately by reference to other indicators. “A court has to analyse factors such as the organisation of the research institution, the likely reliability of underlying data, whether the safety measures are up to date, and any possible self-interest on the part of the plaintiffs”.

So should judges sometimes be given the task of protecting the population from science? Johnson says no: “Scientists are not the bad guys”. Science is in fact a humanistic, noble endeavour that should be protected and supported. Of course there are experiments that bring certain risks with them. “Sometimes, scientists are also prepared to take greater risks than outsiders would. And in such cases, judges can perform a mediating function”. jr

Illustration: Christoph Frei

Ideological battles in the classroom

Judges define natural science

2005 / Parents vs the school board

The theory behind ‘intelligent design’ is this: Living beings are too complex to have been able to emerge merely by evolution. Neither chance mutations nor natural selection can explain specific characteristics of life, which is why it needs the intervention of a supernatural, intelligent designer.

The school board of Dover, Pennsylvania, decided that this theory should be taught on an equal footing with Darwin’s theory of evolution. In 2004, they insisted that biology teachers should read a corresponding declaration to their students.

Some teachers refused. Together with parents, they filed a complaint, demanding that intelligent design should be banned from biology lessons. In 2005, after a six-week-long lawsuit, the Pennsylvania Federal District Court made what was a path-breaking judgement, namely that intelligent design is not an issue of natural science, but religious creationism camouflaged as science.

The biologist Nick Matzke is the former director of the National Center for Science Education in the USA, which campaigns against teaching religious theories in science lessons in American schools. He regards the Pennsylvania judgement as having had a significant, sustainable effect. “This case was very important in demonstrating that teaching intelligent design goes against the separation of Church and State, and is thus contrary to the US Constitution. It has also meant that intelligent design is no longer taught in schools”.

A core aspect of the Dover case was an analysis of the question as to what constitutes ‘natural science’, and whether intelligent design can be regarded as a scientific competitor to the theory of evolution. The court’s answer to this was clear: an assumption of the existence of a supernatural designer can be neither verified nor falsified and thus cannot be the object of scientific enquiry.

This case shows that courts also come up against the challenging task of engaging with scientific theories, besides their everyday work of actually applying the law. Matzke doesn’t see this as a problem. On the contrary, “courts often decide on things that have scientific content”. He believes that the courts should also adopt a scientific position, practise critical thinking, employ experts and scientific standards when passing judgement, and thereby endeavour to determine the truth to the best of their ability. jr

Illustration: Christoph Frei

Doubting therapy

Judges open up research data

2016 / Researchers vs the university

On one side, there is the large British study (PACE) potentially demonstrating the efficacy of psychotherapy in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. On the other side, researchers and patients argue that the illness has biological origins and have openly criticised the study. In between the two lies the data compiled by scientists.

The Queen Mary University of London had rejected requests to access the data. It said that the participants did not provide consent for the data to be published, that the patients could in fact be identified from the anonymous data, and that the campaign against them was being led by activists. These grounds were eventually overturned at appeal, and in September 2016, the courts ordered the publication of the data. This has caused questions to surface regarding the methodological approach to the interpretation of the results, which will only further fan the flames of this debate. dsa

Illustration: Christoph Frei

Hacking the climate

Hacker attack

2009 / Climate sceptics vs scientists

One British newspaper described it as the “biggest science scandal of our generation”. But it was the ‘climate scandal’ that wasn’t. The story was this: in autumn 2009, the servers of the University of East Anglia (UK) were hacked, and over 1,000 e-mails and 3,000 other documents were stolen from its Climate Research Unit (CRU). Excerpts were later published in the Internet and assorted other media.

This case put the scientists metaphorically in the dock, because climate sceptics and the media pounced enthusiastically on apparent uncertainties in the climate debate. E-mails that were either misunderstood or taken out of context caused a sensation because they suggested that the climate scientists had covered up all the results that didn’t suit them.

In total, eight independent investigations by expert groups – parliamentary committees, universities and scientific academies – came to the conclusion that the research results of the climate scientists could not be disputed. The only criticism that remained was that the researchers had not made their data publicly available, and that they had in part been guilty of sloppy work by conflating different datasets without specifically declaring that they had done so.

The chemist and Nobel Laureate Paul Nurse believes that this demonstrates why scientists must engage in a constant dialogue with the public and the media. In his then function as President of the Royal Society, he got to grips with ‘Climategate’ in the BBC documentary film ‘Science under attack’. His most important realisation at the time, he says, was that some politicians, media representatives and activists let themselves be led largely by their ideology instead of by scientific facts and reason. This is also why he finds it counter-productive if the media and a critical public are encouraged to regard science itself as an object of contempt. jr

Illustration: Christoph Frei

Don’t free the wheat

Residents fear genetically modified wheat

2003 / Activists vs biologists

In 2003, Greenpeace activists used a pile of dung to sabotage a field study with genetically modified wheat that had been planned by ETH Zurich. This protest was the culmination of a long approval process that had begun with a research application back in 1999 and that had wandered from one federal authority to another for four-and-a-half years, totalling 500 pages of documents (including all requests, refusals and appeals). Concerned residents united with Greenpeace to file a complaint that ultimately landed with the Federal Supreme Court, which decided in their favour.

The Court did not, however, decide whether or not it was right to carry out an experimental release of the modified wheat, but whether it was correct to deprive the residents of the right to postpone the release. Beat Keller was later responsible for similar trials as part of National Research Programme 59, but he sees both sides of the problem. “On the one hand, the people working on such a research project often have temporary contracts, and it can take a long time for a final judgement to be made”. An indeed, two postdocs had to halt their research because of the delays involved in granting permission for their work. But on the other hand, Keller also recognises that in a country beholden to the rule of law, such judgements also provide legal certainty.

Should residents be allowed to use legal means to prevent scientific experiments? Keller’s answer is pragmatic: “The law on genetic engineering provides for the possibility of filing objections, and scientists have to accept that”. However, the general public will also have to bear co-responsibility for any negative consequences that result for Switzerland as a centre of research. jr

Illustration: Christoph Frei

False witness?

Banning a review

2016 / Historian vs online platform

A bad review can cause lasting damage to a scholar’s reputation. The normal means of restoring your reputation is to issue a reply to it. The historian Julien Reitzenstein chose a different path, and procured a court order to ban a damaging review of his doctoral thesis on the Institute for Functional Military Science Research during the Third Reich. In early 2017, the Hamburg district court forbade the publication of the review on the website ‘H-Soz-Kult’, an important medium for reviews of historical literature. The operators of H-Soz-Kult indeed removed the review from online access, but then replaced it with a new review – one that extensively paraphrased the old review and quoted from it. af

Illustration: Christoph Frei

Blasphemy

A troublemaker at the stake

1600 / Philosopher vs Inquisition

“Your sentence upon me is perhaps pronounced with greater fear than mine on receiving it”. Thus runs the famous phrase of the philosopher and theologian Giordano Bruno, not long before the Inquisition had him burnt to death at the stake in Rome for heresy. Bruno was a non-conformist thinker who scandalised people with his writings. As an advocate of an infinite Universe and of the Copernican worldview, he had questioned the divine story of creation.

Unlike his prominent contemporary Galileo Galilei, Bruno was not prepared to abandon his beliefs even under fear of death from his inquisitors. “What’s fascinating about Giordano Bruno’s personality is that he was consciously a troublemaker”, says Richard Blum, a professor of philosophy at Loyola University Maryland in Baltimore.

In Bruno’s case, the church wanted to set an example. “The Inquisition had rightly recognised that Bruno’s philosophy was incompatible with Christian dogma”, explains Blum. The decision to execute the dissident Dominican monk was thus made on canonical, political grounds.

Bruno was one of many who were sentenced to death by the Inquisition for ‘divergent’ thinking. But Blum does not believe that these trials had any major impact on the march of progress. He remains convinced that scholars will almost always find a means of defending their theories. jr