Feature: A transition in publishing

Young researchers have to do more than research

What do the ideals of ‘open science’ mean to young researchers? The ‘impact factor’ of journals has long been considered of prime importance, but it’s meanwhile frowned upon. Is it still important for a researcher’s career prospects? It’s complicated.

The PhD student’s data actually looked fantastic. But now that she’s presenting her results at a conference, her peers get bored. She’s a flop. | Illustration: Melk Thalmann

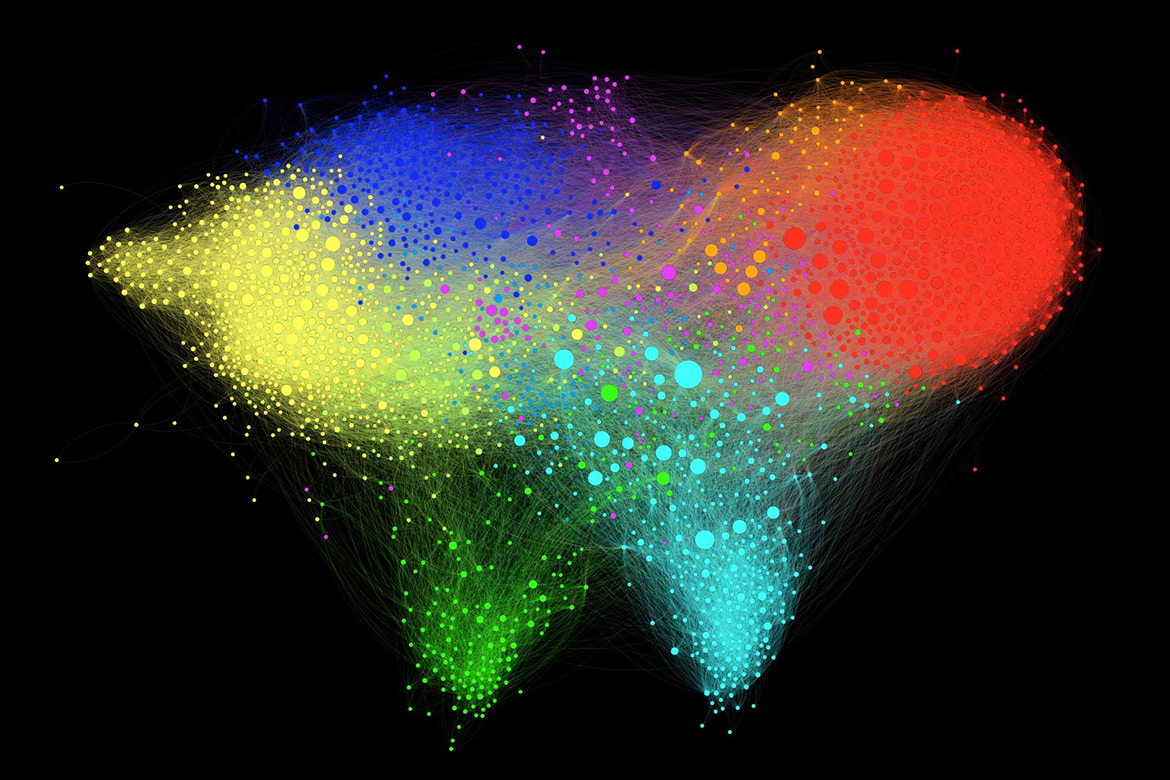

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, Emma Hodcroft freely admits that she was an “average postdoc”. She was an epidemiologist at the University of Basel, working with colleagues on the public software platform Nextstrain. It analyses the genetic material of newly emerging viral mutations and displays the data in graphic form. Despite the relevance of her research, Hodcroft initially remained in the background with everyone else. Then she started tweeting.

Postdocs and doctoral students today make up the bulk of young researchers. They move from one fixed-term post to another, clocking up research results and publications along the way so that they might apply at some point for an assistant professorship. Eventually, the aim is that this should then lead to a full professorship. “This only works out for a small number, because there is a huge number of doctoral students and postdocs, but only a fraction of that number when it comes to professorships”, says Michael Hill, the deputy head of the Strategy Division at the SNSF. The science business is rather like a bulbous wine bottle. At the bottom, there’s a huge mass of aspiring researchers trying to get a professorship, but they first have to pass through a narrow bottleneck. So what kind of success makes the difference in the scramble to get to the top?

The journal shouldn’t matter

“Of course the aim is to select the best”, says Hill. But he is sceptical: “There are lots of answers to the question as to just what that constitutes”. Up to now, academic performance has been measured almost exclusively by a researcher’s number of publications, especially those in high-ranking journals. But these evaluation criteria are currently shifting. Two initiatives are driving this change: First there’s the DORA declaration, which is redefining how scientific achievements ought to be weighted when it comes to filling open positions or allocating funding. Secondly, there is the Open Science campaign, which aims to achieve greater visibility and transparency for science.

DORA stands for the ‘Declaration of Research Assessment’ and was issued in 2013 by the editors of scholarly journals. It criticises how academic performance has always been equated with publications in high-ranking journals, and insists that application procedures should no longer rely on the powerful ‘journal impact factor’ that is based on the average number of citations received by articles from a specific journal. By its very definition, this average value says nothing about the quality of an individual article. Instead, good research ought to be rewarded without regard for the journal in which it appears. In addition, other scientific achievements now ought to be honoured, such as producing important computer models and datasets, or the ability to exert an influence on politics. This should make selection processes fairer – especially for researchers at the beginning of their careers.

The long path to the ideal

Most Swiss universities have long since signed DORA, and the SNSF is providing financial support for this initiative. However, bringing DORA into the conference rooms and offices of research group leaders is easier said than done. This is because the initial pre-selection – an inherent part of application procedures – means that the decision-makers have to filter out many applicants at the start. Metrics like the journal impact factor are incredibly useful in such cases, and it also helps if someone has published in what are regarded as the top journals. Furthermore, the people who make these decisions – research group leaders, professors and the members of evaluation committees – are the living proof that the existing system ‘works’, as they probably got their jobs in part thanks to those self-same metrics.

Proof that there hasn’t been an automatic shift in opinions was provided two years ago by a call for applications from a group leader at ETH Zurich. He had a postdoc position free, and was looking for applicants with a high journal impact factor in their publications, even though ETH had long since committed itself to DORA. It must be said, however, that his blatant disregard for DORA’s principles was strongly criticised on Twitter by the research community. The group leader in question subsequently had to apologise, and rewrote his call for applications.

“We have to broach this topic again and again”, says Ambrogio Fasoli, Associate Vice President for Research at EPFL. He has already chaired several appointments committees for both assistant professors and full professorships. “There are a lot of things that we’re already doing right in these processes”. But Fasoli also admits that many of his colleagues are still very attached to the old impact factor. Nor has he any way of controlling how the approximately 250 professors at EPFL go about recruiting the members of their groups.

Is it worth investing the time?

Back to Hodcroft. Before the pandemic, she had 800 followers on Twitter. “I soon noticed that many of my acquaintances were asking me the same questions about the virus and about how it was spreading”, she says. That’s why she began answering these questions in Twitter threads – in a snappy way that was easily understood. Today, she has over 65,000 followers. Meanwhile, she has appeared in countless TV interviews and articles in the media. There is no doubt that she has played a decisive role in shaping the public discourse on the virus. But will this also help her in her career? On the one hand: “Yes”, says Hodcroft, who now has a postdoc at the University of Bern. “My increased visibility has brought me new research collaborations”.

But on the other hand, this increased visibility can’t simply be translated into an academic career – at least not in a way that would reflect the energies expended and the influence gained. Hodcroft’s most successful threads have been re-tweeted and liked tens of thousands of times, but they each cost about six hours of her time – time that she then cannot invest in her research. In other words, despite DORA, the uncertainty remains as to just how such achievements are actually weighted, especially in comparison with someone’s actual publication list.

Be visible, or perish

Opening up what is considered to be a ‘scientific achievement’ might be a desirable process, but it is also part and parcel of another trend: Open Science. The idea behind this is that publications and science data ought to be freely accessible to all. Open Access (OA) refers to the free availability of publications, Open Research Data (ORD) to the availability of scientific data. “Both of these give researchers greater visibility”, says Luis Velasco-Pufleau, a musicologist at the University of Bern and a member of the ‘Junge Akademie’, where he is engaging with the topic of OA. But he also points out that it increases the pressure on researchers to be visible: “The old phrase ‘publish or perish’ for scholars has given way to ‘publish and be visible, or perish’”, he says.

Nevertheless, he believes that the advantages of OA clearly outweigh the disadvantages, especially for young researchers, and that the same applies in general to the philosophy of making scientific results open to all. This is because the growing number of OA journals is providing more opportunities to publish. “We are no longer exclusively dependent on the big publishing houses that used to have a monopoly on scholarly publications”, says Velasco-Pufleau. In fact, he adds, many OA journals that have only recently been set up are actively helping young researchers to publish their results. He himself is on the editorial board of two international OA journals. What’s more, you also have the opportunity of presenting your other achievements online, not just publications. You can make datasets available, or instances of having had an influence on politics and the general public – like the case of Emma Hodcroft.

At the beginning of a culture shift

“Most young researchers find it perfectly natural to publish on open access”, says Micaela Crespo Quesada, who is responsible for OA at the University of Lausanne. But it is far from the case that all research results are currently being published in an open-access format. At the University of Lausanne – if you include all publications, including books – the figure now stands at 56 percent. “The share of OA is rising continuously, but slowly”, says Crespo Quesada. Older, more established researchers sometimes have trouble with the very idea of OA, not to mention the effort it involves. Among journals themselves, very different models for open access have emerged. One of the most expensive is the renowned journal ‘Nature’. Hodcroft’s research group had to pay some USD 10,000 to be able to publish their latest research article on open access.

Things get even more complicated when it comes to ORD. The idea is that this data should be available for use by many different researchers in a wide variety of studies. “It’s also the case that making data openly accessible increases trust in science”, says Matthias Töwe, the head of the group Research Data Management and Digital Curation at the library of ETH Zurich. “Sharing data really ought to be a natural aspect of good scientific practice”. This is already the case in some research fields, says Töwe – such as in earth science and climate science, where researchers naturally rely on the same datasets. But elsewhere, many researchers are still reluctant, either for fear of giving their competitors an advantage, or because of the resources that they have to invest.

This is because data has to be prepared, standardised and comprehensively described to make it usable for others, and all this takes a lot of work. “If we’re going to promote ORD, then researchers are going to need both assistance and incentives to invest the resources necessary”, says Töwe. It would be conceivable, for example, to offer grants for such projects. “We have to find ways of recognising the merits of these services to science and to integrate them into the CVs of researchers”. But until that happens, Töwe is wholly aware that young researchers in particular will find it difficult to invest the time and energy necessary to put data on open access. This is another area in which high-flown ideals are still to be realised properly in the real world.

In principle, all these trends – DORA, OA and ORD – are opening up the horizons of what counts as scientific achievement so that in future there might be a proper appreciation of datasets, computer models and achievements in communication alongside good, traditional research publications. But we are only at the beginning of this culture shift.