Feature: A transition in publishing

Those who publish first

Publishing as much as possible, as fast as possible, seems to be the be-all and end-all in science and scholarship today. We take a look at how publications became so important, and where things stand today in the different disciplines.

A postdoc is horrified to find that a competitor has already published almost exactly what he wanted to. And her proofs are better than his. He’s overcome with envy and anger. | Illustration: Melk Thalmann

The sole extant private letter from Isaac Newton to Gottfried Wilhelm Leibnitz reveals not a hint of their later mudslinging bouts. In it, Newton, the discoverer of gravity, affirms in October 1693 that he “values friends more highly than mathematical inventions” and that he is “an unchanging friend” to Leibnitz. Soon afterwards, however, what is perhaps the most infamous, ugliest ever dispute about scientific precedence broke out. Newton’s disciples accused the German mathematician and philosopher Leibnitz of having stolen essential elements of calculus that Newton had published in 1684. This led to a charge of plagiarism that was investigated by a commission of the Royal Society in 1712. The commission found Leibniz guilty and expelled him from the Society shortly afterwards – though in fact its members had been appointed and steered by Newton.

Letters as precursors of papers

This dispute occurred at a time of scientific upheaval, a time when there was an abundance of new discoveries, although it was a time when there were as yet no generally accepted mechanisms by which to clarify who had determined something first. Discoveries were often discussed by letter, not infrequently in the form of circulars. The letters that were sent to the newly founded academies and learned societies, and that were subsequently discussed within their circle, essentially attained the status of a published paper.

The secretaries of these societies played a crucial role – mediating, forwarding letters or copies to others, and putting selected writings up for debate. Henry Oldenburg was the first secretary of the Royal Society of London that was founded in 1660, and he rose to assume the position of an editor by publishing the journal The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, in which he wanted to give an “Accompt [sic] of the Present Undertakings, Studies and Labours of the Ingenious in Many Considerable Parts of the World”.

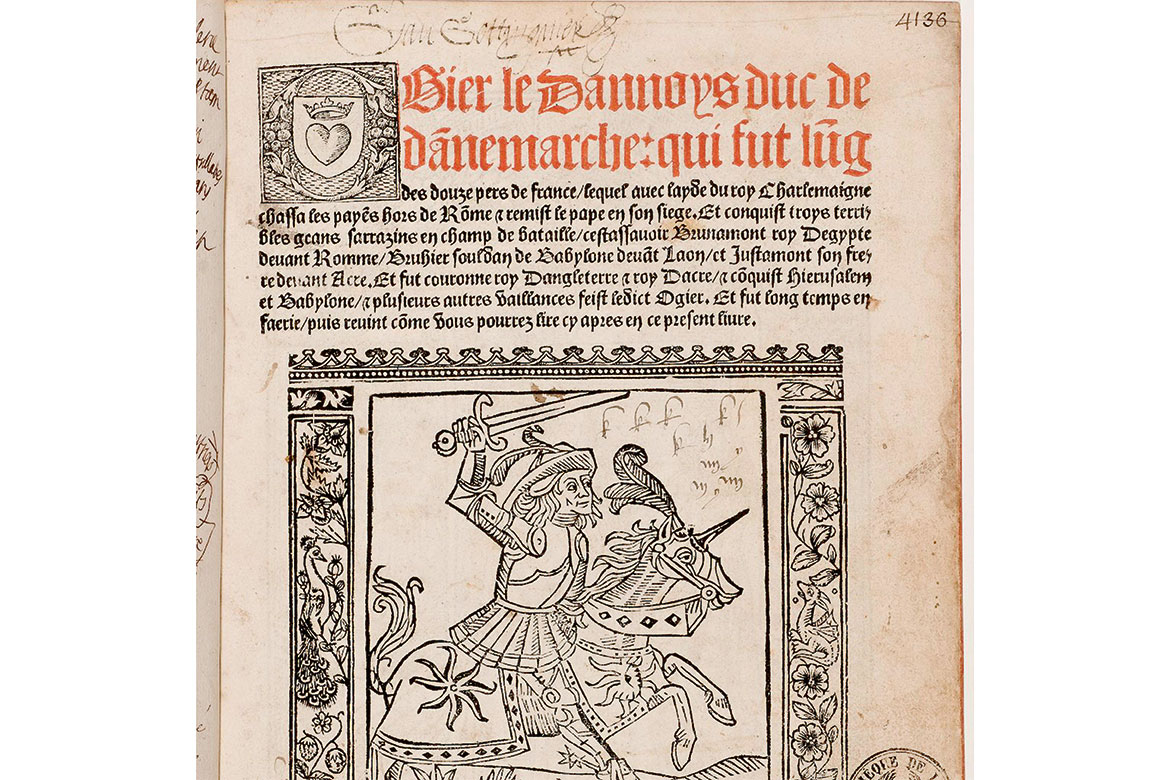

The Philosophical Transactions (first edition: March 1665) are regarded as a precursor of today’s scientific journals, alongside the Journal des sçavans (Paris, January 1665) and the Giornale de’ Letterati (Rome, 1668). In contrast to the first publications of the academies, which were encyclopaedic in nature, these periodicals aimed to bring what was new. In the Philosophical Transactions, each article presented at least one experiment or observation. But there were plenty of curiosities and gossip too.

Counting big

“These early journals have little in common with the strictly formalised journals and papers that we know today, especially in the natural sciences”, explains Mathias Grote, a historian of science at Humboldt University in Berlin. And yet they were pioneering in character. As periodically published media featuring short articles, they offered more and more researchers a quicker means of disseminating their results from the 19th century onwards. It gradually became unnecessary to publish an entire book if you want to publicise your research discoveries.

With the emergence of the different academic disciplines and professional societies from the mid-19th century onwards, journals with universal pretensions began to develop into professional journals whose specialised contents, more rigorous format and innovative quality assurance processes distinguished themselves both from their predecessors and from commercial journals with links to industry and commerce (see the box on peer review).

Researchers were still under little pressure to publish. This changed during the Cold War, when the sciences became involved in the arms race and research funding enjoyed massive increases. The number of a researcher’s publications and the citations that they generate in turn became established as criteria for awarding contracts and appointing professors. It came to be believed that these quotas could help to provide an objective evaluation of a researcher’s competencies and achievements. “Why shouldn’t we apply the techniques of science to science itself?”, asked Derek de Solla Price in a lecture in 1962. He was the co-founder of scientometrics, the science of measuring scientific activity. From the late 1960s onwards, the data required for this was to be found on citation databases such as the Science Citation Index, the Web of Science, Scopus or Google Scholar.

Expensive open access

“Publish or perish” became the law in the scientific community. In the 1980s, global publishing consortia such as Springer, Elsevier and Wiley acquired almost all the relevant journals and editions with a high impact factor, enabling them to reach a position of power that meant they generated huge profits. Their business model was as simple as it was ingenious. Researchers submitted their manuscripts for free, so-called ‘peers’ reviewed them free of charge, and the universities – which were all in competition with each other – acquiesced when the subscription prices kept rising.

But this model came under pressure from the 1990s onwards. Libraries were no longer willing to pay up to USD 20,000 for a journal subscription, and more and more authorities began demanding the free publication of research results from projects funded by governments. The year 1999 saw the founding of the first-ever open access publisher: Bio Med Central. It is now owned by Springer, and with its more than 180 peer-reviewed journals it is the world’s largest open-access provider. The publishers adapted their business model accordingly. It was no longer the libraries who were the main source of funds, because the researchers themselves began paying for their publications to appear in these open-access journals.

Parallel to this, online platforms began to emerge where researchers were able to publish their studies free of charge, mostly without any prior peer review. Such “preprints” became especially established in medicine, biology, mathematics and physics. Accelerated procedures are also offered by the recently created format of the “registered report”, which is mainly used in biomedicine. Here, the methods proposed for a study are committed to paper and submitted to the journal where they are then reviewed; only afterwards is the study actually carried out.

The frequent and fast are more respected

According to Andreas Boland, an assistant professor of molecular biology at the University of Geneva, “it is not yet possible to guess which format will prevail in the future”. In molecular biology, speed is crucial. That is why many manuscripts are placed on the BioRxiv platform in the form of preprints. But Boland also finds developments such as the Review Commons platform interesting, where a quicker peer review is carried out independently of the journal. However, if a piece of research is of great relevance, then it is still often decided to publish it in a well-known journal such as Nature, Cell or Science. In June 2021, Boland’s group was able to publish an article in Nature, “so of course we popped open the champagne”.

The number of preprints has also increased greatly in physics, says Rachel Grange, a professor of quantum electronics at ETH Zurich. “But publishing in a peer-reviewed journal still remains the gold standard, especially for young researchers”. And your number of publications remains important. “I always say: Quality matters, but quantity too, unfortunately”, she says. Most funding bodies today require open-access publication, which sometimes puts researchers in a dilemma. “Journals charge CHF 2,000–6,000 per article for open access. Not all research groups can afford that”. Even the cheaper option with an embargo period of 6/12 months can be problematic. This is because funders often expect researchers to publish a freely accessible publication immediately after the completion of a project or at the end of a grant.

The humanities and social sciences use a wide spectrum of publication forms. In the field of history, for example, articles are not only published in peer-reviewed journals, but also in anthologies, says Svenja Goltermann, a professor of modern history at the University of Zurich. “In the past, such volumes used to have room for almost everything, but in many cases they also included papers of little relevance”. In the meantime, however, well-known publishers such as Cambridge University Press and Oxford University Press have begun conducting peer reviews for their anthology volumes. “As a result, these publications have increased in importance”. Goltermann explains that the so-called ‘second book’ is now also almost indispensable for an academic career. This refers to a monograph written after one’s doctoral thesis, and on a different topic from it. Although there is a trend in various disciplines towards cumulative doctoral theses – in other words, a compilation of several essays related in content – the monograph will continue to be indispensable in the historical sciences in the future. Some arguments can only be developed in the form of a book.