The fierce debate about tuition fees: here are the facts

Increasing university tuition fees always prompts fierce resistance. But not a lot is actually known about the impact of such increases. We check the facts.

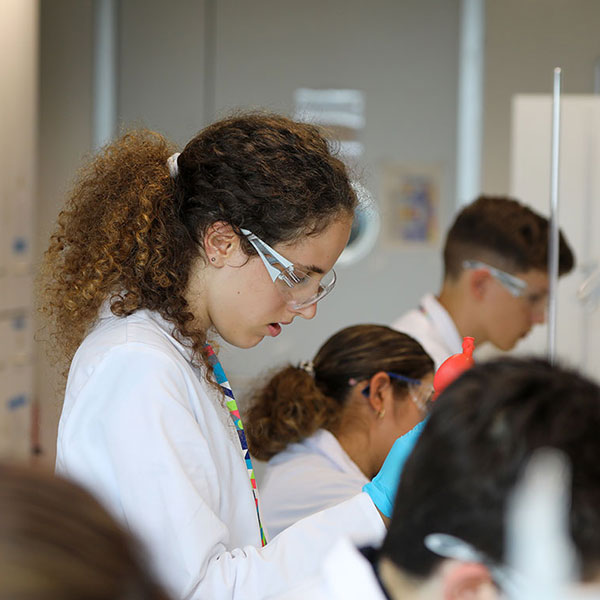

When a potential rise in tuition fees is announced, university and school students are up in arms. They see this as placing limits on their educational freedom, and an extra hurdle to getting a degree. But the universities argue that they need more money. | Image: Keystone/Walter Bieri

Political battles are raging at several Swiss universities. ETH, EPFL and the universities of Bern, Basel and Fribourg would like to increase their tuition fees by several hundred francs a year. Students’ associations and their supporters are up in arms about it. They fear that students from less-well-off families will suffer. Furthermore, the additional revenue would only cover a tiny proportion of the universities’ budgets.

Are their objections justified? And what is the actual impact of higher tuition fees? Investigations carried out in recent years, both at home and abroad, have resulted in contradictory findings. The study ‘Socially acceptable tuition fees’ (available only in German), commissioned by the Swiss Conference of Cantonal Ministers of Education (EDK), came to a clear conclusion in 2011: “It is possible to make a significant increase in tuition fees alongside appropriate, flanking measures to ensure that such an increase is socially acceptable”. But these “flanking measures” are very necessary. According to the investigation in question, an increase in fees of just CHF 1,000 could have a critical impact on some students and their families. The study concluded that the family budget could be put under great strain, or the students would be compelled to take on extra, outside work that could in turn endanger their prospects of success at university.

The cantons should compensate for excess expenditure

This is why this study says a marked increase in tuition fees would have to be accompanied by fundamental adjustments to the overall system of fees and scholarships. The whole financial structure would have to shift. If tuition fees increase from CHF 1,500 to 2,500 per year, the Swiss universities will earn some CHF 130 million extra. But at the same time, CHF 33 million in scholarships would have to be promised to students with lower incomes. Individual cantons would be affected differently, and would presumably compensate for this extra expenditure by reducing their inter-cantonal payments to the cantons where the universities are situated.

The Association of Students at ETH Zurich also believes that some students will find it difficult to pay an extra CHF 500 per semester. According to its calculations, tuition fees make up between 8 percent and 24 percent of a student’s budget. In total – according to the figures published by ETH Zurich – tuition and living costs come to between CHF 16,000 and CHF 24,000 per year. According to the subject they study, a further CHF 800 to CHF 4,800 costs can be incurred for laboratory materials and excursions.

In their article ‘Tuition fees and their consequences – an overview of the state of research as a contribution to the current political discussion’ (available only in German), researchers from the University of St. Gallen came to the conclusion in 2013 that higher fees resulted in a decrease in the number of students enrolling. But expectations also change. If their fees go up, students want a higher quality of education, and would regard their future employment prospects as having improved. Universities that have a good reputation and that are said to offer high-quality teaching would be able to demand higher fees than universities with lower standards, claims the report. But there could be a negative impact on the “social and gender mix” of the student population.

Today, the Swiss universities charge very different tuition fees. The cheapest place to study is Geneva, where students pay an annual fee of CHF 1,000. ETH Zurich and EPFL are also rather cheap, at CHF 1,160 a year. On the other hand, the University of St. Gallen (HSG) charges CHF 2,500 per annum, and the University of Lugano CHF 4,000.

Different international models

If one casts a glance beyond the Swiss borders, one finds very different models in use. England and Wales only introduced tuition fees in 1998, but they have the highest fees in Europe today, with universities charging up to GBP 9,000 per year. This does not deter students from underprivileged families from studying, however. Between 2012 and 2017, the number of students from disadvantaged regions rose by 30 percent, despite the fact that tuition fees reached their high point at this time. However, students now leave university with large debts that have to be paid back over many years.

In Germany, studying is free almost everywhere again. In 2006, seven federal states introduced tuition fees, but they scrapped them again in 2014 after major protests. These states include Baden-Württemberg, where tuition fees of EUR 1,500 per semester have again been charged since the last winter semester – for newly enrolled students and for non-EU students. As a result, the number of enrolments of international students fell by more than 20 percent.

Contradictory studies

There are contradictory opinions about the impact of tuition fees. Researchers at the German Centre for Higher Education Research and Science Studies (DZHW) have claimed that tuition fees are of little use, but don’t do much damage either. Their effect, say the researchers, is far smaller than is anticipated (or feared) and they hardly have any impact on the number of applicants because rising fees are usually accompanied by higher student loans or scholarships. After the DHZW reported its findings, the Berlin Social Science Center (WZB) went on to present two studies that were themselves contradictory. In 2011, they found that tuition fees had no impact on what young people decided to study. Three years later, they wrote that those primarily discouraged from studying by tuition fees had parents who hadn’t attended university.

In 2011, France also abandoned all tuition fees. Instead, students have to pay enrolment fees equivalent to CHF 200 for a bachelor and CHF 400 for a doctorate. In Italy, the average tuition fee is roughly equivalent to CHF 1,000. Studying is free in the Nordic countries Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden, at least for EU and Swiss citizens. Students from elsewhere have to pay up to EUR 16,000 per year, depending on the course they take. In the USA, too, studying at a university can be very expensive, costing tens of thousands of dollars each year at the top institutions.

In international terms, the fees charged in Switzerland are moderate, and its universities are excellent. The increases planned are of a few hundred francs, so they aren’t going to change this overall picture. But the question remains as to what these higher fees will actually bring to the universities. We have an answer from ETH Zurich at least. The planned increase of CHF 500 per annum will bring in extra income only totalling a fraction of a percentage point of its annual budget.

Michael Baumann is a freelance journalist in Zurich.