Neglected science

Where researchers fear to tread

A whole host of unanswered scientific questions can be revealed, if you just look for them. There are various reasons for this. We here go on a voyage of discovery through a land of taboos and suppressed knowledge.

Sometimes the hardest thing is taking a good, hard look at yourself. That’s also one of the reasons blind spots arise in science. | Illustration: Joël Roth

“Today, it’s become a taboo to claim that not every female academic is ambitious in her career”, the economist Margrit Osterloh told the weekly magazine Die Weltwoche this summer. The article in question was about the fierce reaction she had experienced after publishing a study together with the sociologist Katja Rost. Among the issues they raised was the fact that – so they insist – not all female students have ambitions for a fulltime academic career, but would rather work part-time.

The outcry they prompted would seem on the surface to confirm that they, too, were the victims of the so-called ‘cancel culture’ that has featured prominently in media reports in the past few years. The offended parties in this case were primarily left-wing groups.

The psycholinguist Pascal Gygax from Fribourg has investigated the considerable impact of the generic masculine on the way we all think, publishing a book on the subject two years ago. He told Horizons at the time: “In the seventeen years I’ve been working on this subject, I’ve never received so many insults”. In his case, the offended parties were on the right of the political spectrum.

Both these examples show how political convictions and media attention can develop a malign dynamic that can discourage young researchers in particular from working in fields like these.

See no evil, speak no evil

Whether we should be talking about such cases as ‘taboos’, as Osterloh does, is another matter altogether. It might help us to consider a definition coined by the Austrian science historian Ulrike Felt on a TV programme for the channel ORF: “Taboos constitute what is unsaid and unspeakable; they are implicit instructions for how we should act”. The fact that women supposedly prefer to work part-time is neither something unspoken nor a forbidden topic of debate; the same applies to claims about the impact of the generic masculine. Both have been the subject of controversial discussions in society over the years. In other words, neither can be classed as a ‘taboo topic’.

These are nevertheless topics that touch on very specific beliefs, which is why they meet with resistance. Fear of negative reactions can lead to blind spots in research. The German sociologist Jan Philipp Reemtsma has defined these as follows: “A blind spot is not what you don’t see, but a spot in your eye that prevents you from seeing something in your actual field of vision. That spot might well be small, but it’s still there”. This means something remains shielded from our sight, even when we’re looking in its direction.

The boundaries between taboos and blind spots are naturally fluid. These are not clearly defined categories, but we can nevertheless use them as guideposts when we investigate research topics that have been suppressed, frowned upon or forgotten. Such topics have always been significantly greater in number than those that are currently being beaten with the hammer of cancel culture.

Sex with children

The example of paedophile violence reveals the dynamics at play when a topic is blanked out for a long time as a field of research. The German education researcher Meike Sophia Baader of the University of Hildesheim has been investigating sexualised violence that occurred within the so-called ‘reform’ movements, i.e., reform pedagogy, educational reform and the sexual liberation movements. She explains how sexual liberation led to societal taboos about sex being dismantled in certain circles in the late 1960s. “They began to regard any sexual activity as good”, she says – and that even included sexual acts with children.

Baader proves her point by referring to the education science magazine ‘Betrifft: Erziehung’, which in 1973 published a focus issue entitled ‘Paedophilia – A crime without victims’. In the early 1970s, this magazine had a higher circulation than all other such publications on education science in the Federal Republic of Germany: “It was a forum both for education reformers and for a younger generation of critical researchers in education”.

According to Baader, this positive attitude to sexuality, along with the fight against social taboos about sex, resulted in people becoming blind to other aspects. “The rhetoric of consensual sexuality between children and adults ignored the power relationships that exist between the different generations”. In all these discussions, she says, no one made any clear statement that children might be allowed to say ‘no’ to sexual matters.

This ignorance of the children’s situation had considerable consequences. For example, in his book ‘Plädoyer für Leihväter’ (‘The case for surrogate fathers’), published in 1989, the well-known education scientist and sexologist Helmut Kentler described how, twenty years earlier, he had paired young people from the street with paedophile men as part of an ‘educational experiment’. Kentler knew full well that these pairings resulted in sexual acts. “But he was convinced that this did not harm the young people in question because their ‘surrogate fathers’ treated them lovingly and were preparing them for society”, says Baader.

Where it hurts

Up to this point, the suffering of the victims was a blind spot in progressive educational science. A supposedly liberating perspective on sexuality had resulted in tunnel vision. Kentler’s experiments continued into the 2000s; in the case of the progressive German boarding school Odenwaldschule, extensive sexualised violence against children and adolescents even continued into the mid-2010s. “It took a long time for those who were affected to get the attention of the media, politicians and academics”, says Baader. “At first, something like this constitutes a kind of ‘secret’ knowledge. That’s the crux of the matter. It’s spoken about, but no one’s listening”.

As recently as 2020, people in the German Educational Research Association (GERA) were still referring to sexualised violence against children as a ‘dirty’ subject. “It can be a long process before a discipline is also prepared to look at itself”, says Baader. “Initially, the topic is a complete taboo, then this taboo is broken, and the topic can no longer be ignored completely. At some point, the topic is no longer a taboo at all. But people still want to push it away”. Such ‘unspeakable’ topics are often enveloped in a diffuse cloud of irrational defensive reflexes – but Baader’s description brings home the reality of them.

Baader won’t stop looking where it hurts. She adds that there are also topics at present that are so unimaginable that they are barely a subject of research at all – such as sexualised violence against infants and toddlers. The same applies to sexualised violence against people in care, such as people with disabilities. “Neither society nor the scientific discipline in question nor the researchers active in it are keen to engage with such topics. They’re also difficult to bear”, says Baader – thereby providing a convincing description of just what constitutes a taboo.

Just too dangerous

Besides topics such as these, ranging from the unspeakable to the unimaginable, there are also areas of research that both society and scientists find so frightening that they prefer not to tackle them at all. For some 15 years now, for example, there has been a controversial debate about the artificial reduction of solar radiation on Earth: so-called Solar Radiation Management (SRM). Some scientists insist that this technology should be banned because its effects are simply too unpredictable. And not just this: they also want research into it to be banned. Their argument is that research will prepare the ground for the later use of this technology. A research group led by Wilfried Rickels of Kiel University has summed up one of the primary arguments against SRM by observing that this research in itself could “prompt morally irresponsible behaviour because its potentially simple solution to the climate problem would lead to fewer restrictions on emissions”.

An awareness of the possible future dangers of this technology is therefore blocking research into it. The situation is similar when we come to cloning, or extracting stem cells from embryos. Both are banned in some countries. In an interview with the newspaper Der Standard, the Austrian science historian Ulrike Felt said: “Most of the time when we’re talking about taboos, we mean something that’s banned. But taboos are unspoken things that mainly concern what may not be said, thought, felt or touched upon”.

Such bans can also crumble when technological possibilities expand. In June 2023, researchers in Cambridge created artificial embryos from stem cells. In an interview with SRF Radio, the Swiss ethicist Ruth Baumann-Hölzle was asked how far research should be allowed to go. She replied: “Ultimately, the so-called technological imperative always prevails, the goal of which is simply what is feasible. For example, the international Biomedicine Agency immediately relaxed certain guidelines after the successful creation of synthetic mouse embryos”.

Unscientific or just old hat?

Even when research has proven certain fears to be unfounded, a topic might still be suppressed – though for quite different reasons. David Gugerli is a historian of technology at ETH Zurich. He recalls how the ETH Research Commission once had to assess an application for a study into whether constructing mobile phone antennas had a negative effect on the price of real estate at their location. The Commission initially wanted to reject it, because it could not be proven that mobile phone antennas had any injurious impact on human health – which according to their logic meant in turn that no one could possibly expect any impact on real-estate prices. Gugerli objected to this decision at the time, “Because research was here being made a taboo on account of its proximity to a topic that was considered unscientific”.

The fear that a supposedly frivolous topic could cause reputational damage no doubt played an important role in all this. Gugerli also mentions other areas that are rarely studied in his discipline. Today, for example, researching into old technologies such as bicycles or corrugated iron is frowned upon among historians of technology. “They’re just not sexy”, says Gugerli. Condemning a topic as ‘uninteresting’ or ‘old hat’ has created a blind spot.

Intense tunnel vision

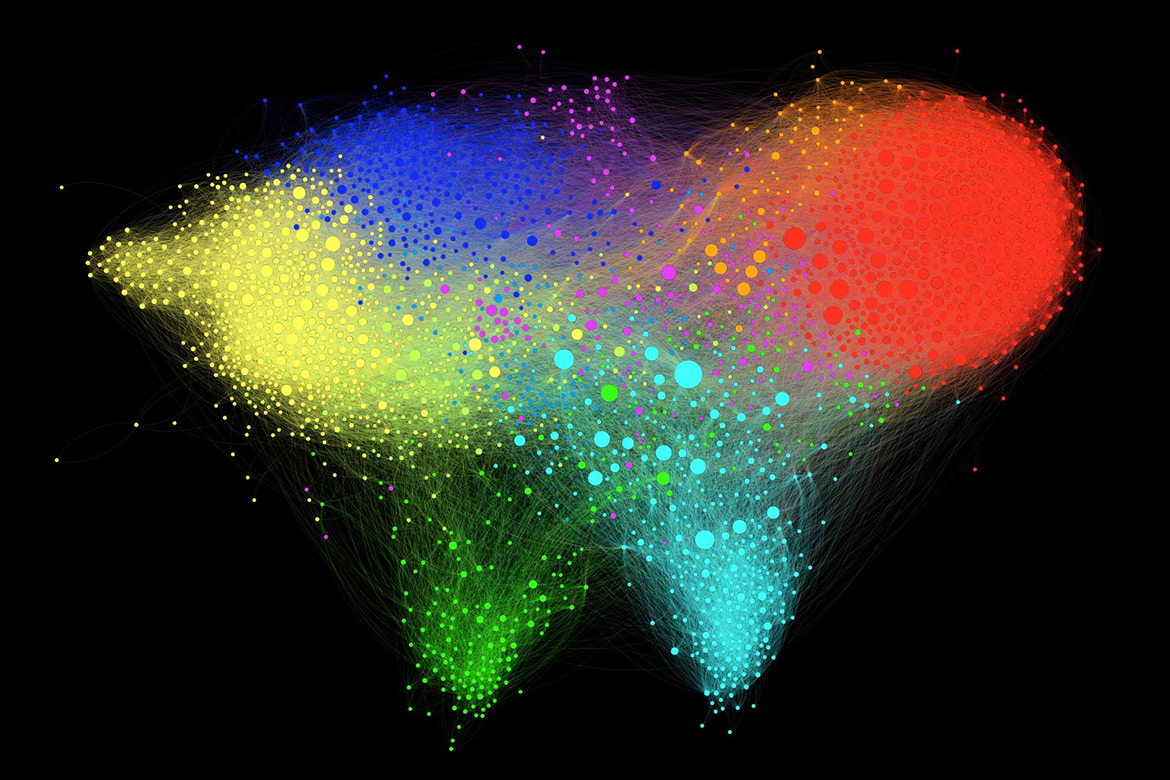

Pascal Germann is a science historian at the University of Bern. He sees another important dynamic at play when subject areas are largely ignored by researchers. “New research paradigms are always emerging. They produce new knowledge and change our view of reality. But they also always produce areas of non-knowledge”. To illustrate this, he mentions bacteriology, which was “one of the greatest breakthroughs in the history of medicine”. From the late 19th century onwards, he says, it was known that infectious diseases were caused by microbes. “From then on, people became committed to microbes as the origin of infection, but in so doing pushed other connections into the background. As a result, research into the social conditions of these diseases was now considered obsolete”.

In the case of tuberculosis, the “killer of the 19th century”, it was “the labour movement that spoke of a social disease”, says Germann. We well know today that tuberculosis was in fact much more prevalent among the lower social orders, and that the decline in mortality was mainly due to improvements in social conditions. According to Germann, “similarly reductionist views” shaped the discussions about Covid-19. Field reports from hospitals had shown very early on that people in precarious jobs were more affected. “But this social dimension was only taken into account over time”. All the same, he emphasises that actual taboos are rarely responsible for topics being excluded from research; it’s certain paradigms and political contexts that are the real reason.

In cases of dominant paradigms or sheer disinterest, blind spots in research tend to arise as collateral damage. They do not come about because someone wants to suppress a topic. Nor is it a problem for science if someone does finally bring these blanked-out areas into focus. But with topics that cause too much hurt, or that question one’s own discipline, researchers specifically avert their gaze. This also applies when content is suppressed for political reasons. It is highly disagreeable for researchers in the fields in question when someone wants to turn their gaze back so that they have to see it anyway. But the ideals of science and scholarship require us also to ask questions that are uncomfortable. In order to live up to these ideals, researchers have to engage in very precise observations and leave no stone unturned, even when they find it deeply unpleasant.