Touch screens in the cage

Eloïse Déaux visits Basel Zoo every week to work with chimpanzees. She observes how they learn in order to improve our understanding of human language.

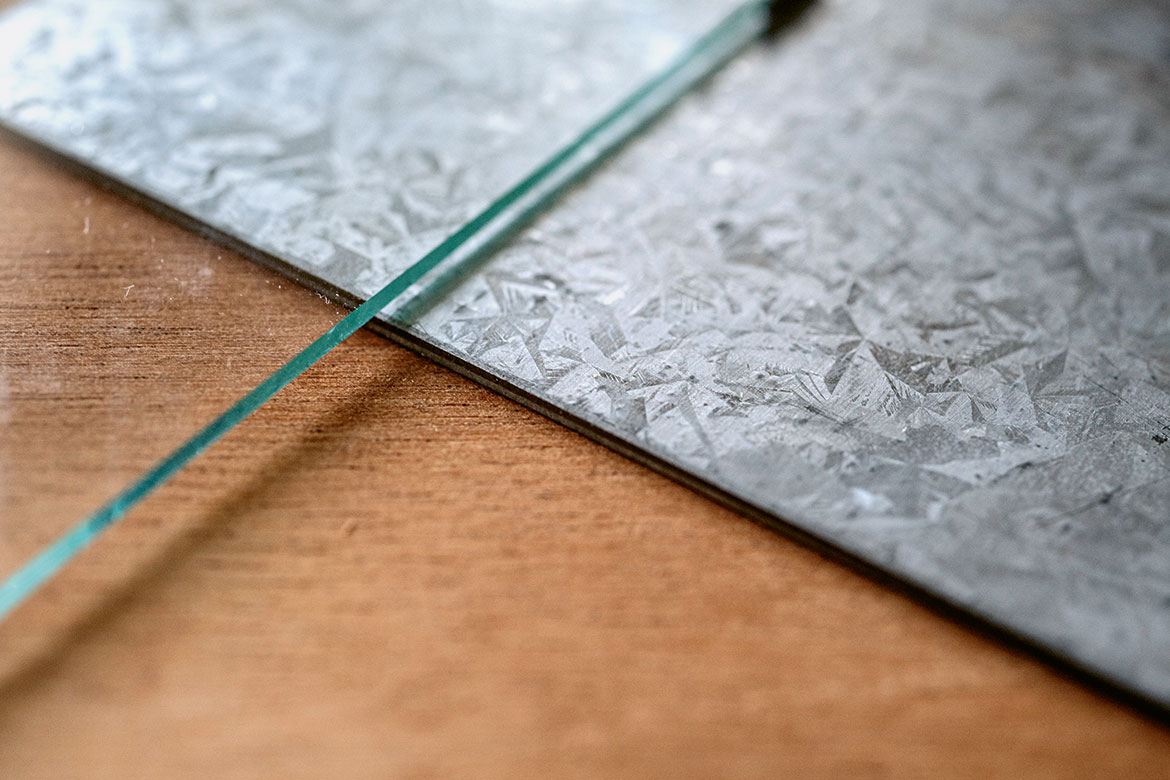

At Basel Zoo, chimpanzees don’t just delight visiting children: they also participate in scientific experiments. Under the eye of Eloïse Déaux, they manipulate a touch screen to obtain food. The biologist wants to understand the role of different types of sound signals in their learning. | Image: Zoo Basel

My day begins with an hour of cleaning. I enter the chimpanzee cage, remove the droppings and food scraps, and wipe the windows. For the zoo keepers, it’s a welcome exchange of good practices; for my fellow passengers on my train home, it’s an unwelcome exchange of odours, given how dirty my clothes can become.

With the cleaning over, my work as a scientist begins. My aim is to understand how social learning in chimpanzees influences the development of their vocal repertoire. To bear this out, I focus my research on ‘food calls’, the sounds made by apes when they eat or discover food.

I am currently studying whether social signals play a cognitive role in the speed of retention of new information. This has involved installing two touch screens in the chimpanzee cage. The screens display pairs of objects that are unfamiliar to the animals: a Rubik’s Cube next to a square pouffe, a hairbrush next to a kitchen whisk. They must then select the image that had been arbitrarily designated as the correct one. As a reward, they receive a piece of fruit.

In the experiment, the computer makes one of two sounds just before the images are presented: a food call or a quick blow of a hammer. Then I look at how many tests are necessary for them to retain the right image. The preliminary results suggest that the food call helps them memorise information faster. But this remains to be confirmed.

During these sessions, I stay behind the screen and give the rewards at the right time. They can see me, but I am never in direct contact with them and I never work unless a zoo keeper is present. The aim is to guarantee the best level of safety for all and also to avoid subjecting the animals to stress.

I’ve previously studied the dingo in Australian wildlife reserves. In the zoo, I am guaranteed to be able to work with the animals for three hours at a time, instead of having to hike for hours through the forest without even being sure of finding my research subjects ... The downside is that zoo populations are smaller and haven’t grown up in a natural environment. There are also certain rules. For example, the animals cannot be separated.

My work depends a lot on the mood of my subjects, because their participation is voluntary after all. The zoo keepers and I agreed I should keep to a maximum length of two 15-minute sessions per day. A red background on the screen indicates to the chimpanzee that he/she has reached this limit. This is very important, in terms of diet and of the proper functioning of the group. The apes’ eating behaviour must not be disturbed by the rewards, nor must conflicts arise over access to the screen.

Smarter than apes

Currently, I have at my disposal three adult individuals who have acquired a sufficient level with which to work. Two others are progressing, while there are four females who are not showing any interest in the screens, although I am hopeful that one day they will participate. I was aware of the neophobic nature of chimpanzees, but I was surprised that it took weeks to encourage them to touch the screens – despite the pieces of carrot placed on it.

Working with chimpanzees pushes you to constantly rethink your tasks. You have to try to be smarter than them, which is not always easy! If there is a way of getting the reward with less effort, they will always find it. For example, one female’s task was to press a square that moved along a random trajectory. She soon worked out that by pressing the same spot repeatedly, the square would eventually pass under her finger ... In such cases, I am the one who has to adapt by changing the computer program.

This research has its fair share of amusing moments too. One day, a female covered my clothes with a handful of excrement that she threw through the grate. Right after, a visitor started asking me some very serious questions about my work, but the smell was so bad that I could hardly keep a straight face!

I am currently conducting a second study to determine if the food calls influence an individual’s behaviour with an unknown food. The ultimate goal is the same: by studying apes’ communication skills, we can better understand the evolution of human language.

Image: Penelope Lacombe

Eloïse Déaux is a post-doctoral fellow at the Comparative Cognition Laboratory of the University of Neuchâtel and is passionate about animal communication and behavioural ecology. She studied biology at Macquarie University in Sydney and wrote her thesis on the acoustic signals of dogs and dingoes.

Interview by Martine Brocard.