Neutering endearment

In German dialects, women are often described in the neuter form, thus ‘ds Vreni’ or ‘s Anna’. But linguists have shown that this does not necessarily imply misogyny or patriarchal disdain.

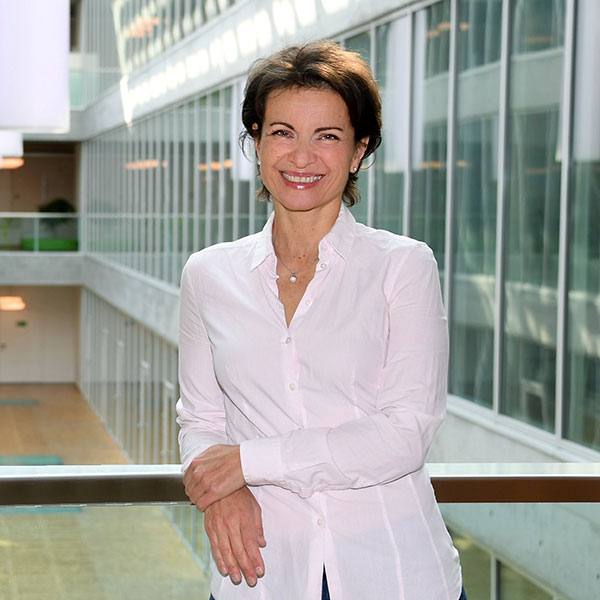

Even the late chansonnier Mani Matter sometimes referred to women in the neuter. That both points to his origins in Bern, but also creates a sense of intimacy with his characters. | Image: Valérie Chételat

We’ll start with a spot of grammar. Don’t worry, just the basics. Unlike French or English, the German language has three genders: feminine, masculine and neuter. As a rule, the gender of people’s names corresponds to their natural gender. Yet in some parts of German-speaking Switzerland, Germany and Luxembourg, women are addressed not with the feminine form, but with the neuter. So instead of ‘die Anna’, it’s ‘das Anna’, and instead of the third-person feminine pronoun ‘sie’, they’re referred to in the neuter, ‘es’. “This use of the neutral gender interested me as a linguist”, says Helen Christen, a professor of German linguistics at the University of Fribourg.

Christen insists that nothing happens by chance when it comes to language. “Gender assignation is used to create meaning”, she says. But what is the meaning in this case? Does the use of neuter signify a derogatory attitude towards women? Does it belittle them, as the Swiss in particular tend to suspect? Together with linguists from Germany and Luxembourg, Christen and her team have been undertaking the first-ever fundamental investigation of the phenomenon. They have carried out their own surveys, analysed old folksongs and evaluated obituary notices. In the case of German Switzerland, their findings thus far offer a differentiated picture.

Dissing and doting

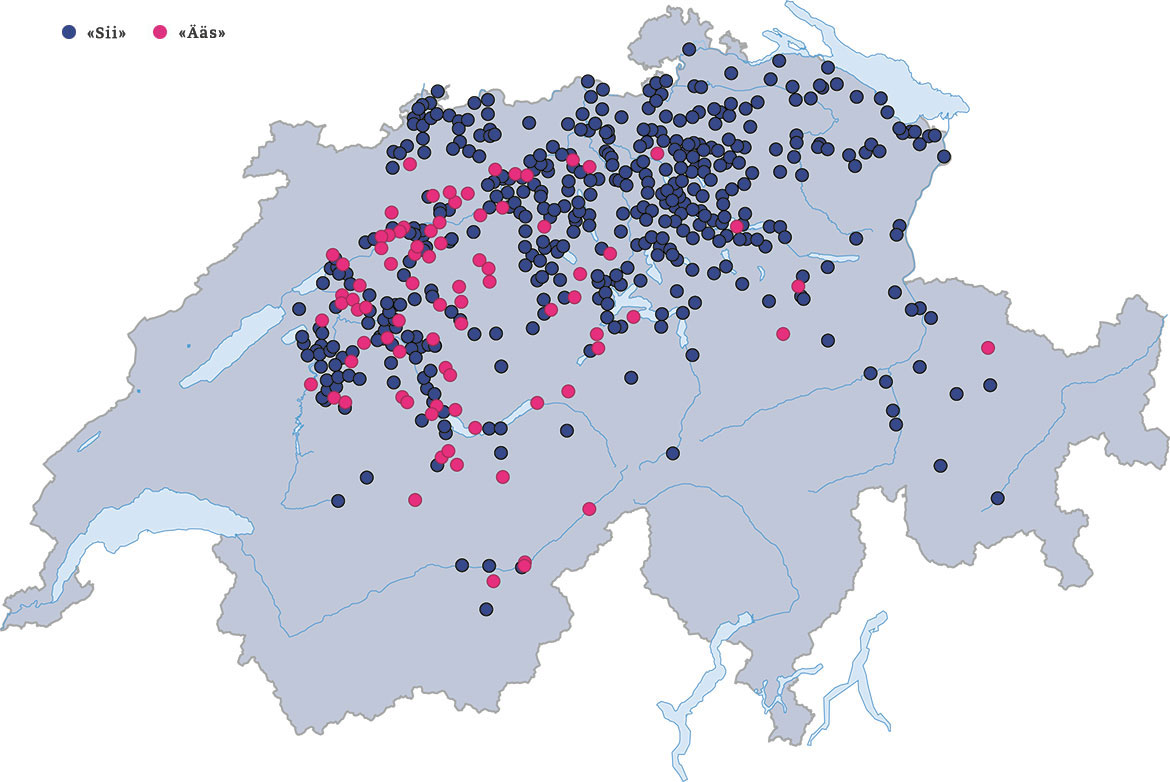

Neuter first names for women are especially common in Central Switzerland and in the cantons of Bern, Solothurn, Basel-Landschaft and Glarus. They have their origins within families and village communities, where relatives and close friends tended to address each other using diminutive name forms. The logical linguistic result of this was the neutral gender: ‘die Verena’ thus becomes ‘ds Vreni’. Over time, personal relations meant that the use of the neuter was extended to women’s names that were not in the diminutive, thus ‘das Pia’, ‘das Judith’. These designations are meant as terms of endearment, says Christen: “They are intended to express intimacy and familiarity”.

Conversely, if someone addresses their sister or an old school friend as ‘Verena’ instead of ‘Vreni’, this creates distance, signifying that their relationship has in some way cooled off. But it is very different, for example, if a woman member of the Federal Council is referred to in public by the neutral gender. In such cases, a ‘pet name’ is inappropriate, and tends to come across as disrespectful. “In the proper context, using the neutral gender comes across as either unobtrusive or positive; in an improper context, its meaning shifts”. Christen also found unexpected new varieties, such as women’s first names with a masculine gender: ‘der Fridu’, for example, applied to a ‘Frieda’ who was a tomboy. And in the Sense district of the canton of Fribourg, she found men’s names with a feminine gender: ‘d Hänsa’ for ‘Hans’.

It’s a he

There was just one combination that Christen almost never came across: men’s names with a neutral gender. When men’s first names are used in the diminutive among close friends, the article and the pronouns remain masculine. The diminutive ‘Fredi’ is thus used in conjunction with the masculine pronoun ‘er’, not the neutral ‘es’. Exceptions do exist in the Bernese Oberland and in the canton of Valais (‘ds Hansrüedi’), but they serve to confirm the rule. Using the neutral gender for someone’s full name is the exclusive preserve of women. You don’t find ‘das Thomas’, for example. “Men’s names seem to immunise their bearers against the neutral gender”, says Christen, who has found that neuter is clearly regarded as more appropriate to images of femininity. To her, this seems to suggest that the dialectal neuter can indeed be traced back to patriarchal notions of gender. The feminine is thus associated with what is diminutive, reduced and more marginal, just as what is private and familial is regarded as the domain of women.

The dialect author Pedro Lenz from Bern has also noticed this ambivalence. He’s especially sensitive to linguistic matters, and long avoided neuter forms for women. “You shouldn’t address adult women like you would a child”, he says. But then one day, a woman reader asked him to sign a book for her with the following phrase: ‘Für ds Elisabeth, mög’ äs no mänge schöne Früelig erläbe’ – literally, ‘For Elisabeth, may it still experience many a lovely spring’. When he protested the ‘it’, the lady in question insisted that ‘äs’ isn’t a neutral pronoun, but a term of endearment. “Since then, I’ve tried to be more open in my opinions about it”, admits Lenz. He even put this experience into a short story. With the freedom we still afford creative writers, he came up with this solution: German doesn’t have three genders, but four: feminine, masculine, neuter, and endearing.

Feminine or neuter pronouns? Answers from an online survey showing whether respondents refer to 'mummy' as 'she' ('Sii'') or 'it' ('Ääs'). | Image: 2. stock süd, source: regionalsprache.de