Scanning corpses

Autopsies improve medicine, but they are conducted increasingly rarely. Pathologists and forensic specialists are investigating whether imaging techniques might be able to replace the scalpel.

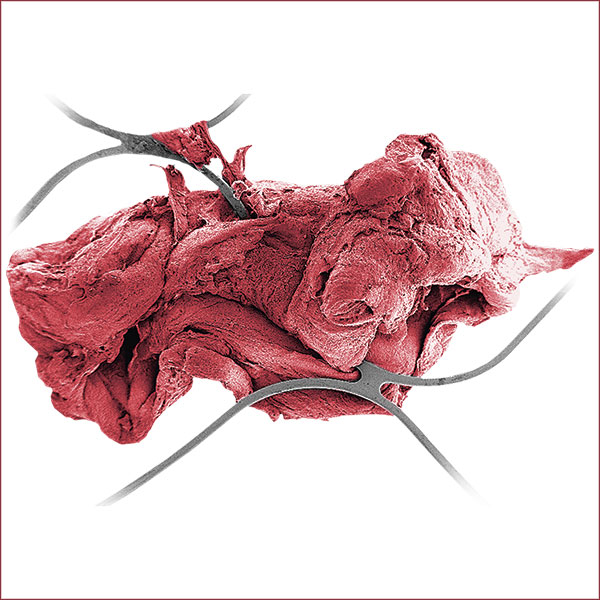

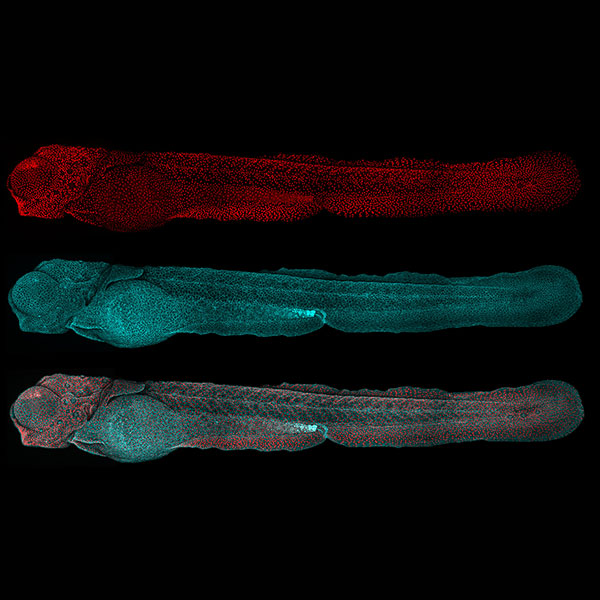

A heart attack, pictured twice: The dead tissue of the septum appears dark in both the classical autopsy (above) and the MRI (see below). | Picture: IRM Bern

Doctors ascertain certainty about the cause of death by carrying out an autopsy. It’s also one of the best methods of quality control in a hospital. It can prove whether or not a diagnosis was correct, what a therapy’s impact and side-effects might have been, and whether anything could have been overlooked. “A hospital that doesn’t carry out any autopsies can’t know why its patients die”, says Alexandar Tzankov, the head of histopathology and autopsy at the Institute of Genetics and Pathology of the Basel University Hospital.

Nevertheless, the number of autopsies carried out annually in Switzerland has sunk from over 8,000 to just under 2,000 over the past 20 years. There are many reasons for this, says Tzankov. Patients or their relatives have to agree to an autopsy, which is not always the case. What’s more, it is often difficult for doctors to ask for permission after having notified a family of a death. And some clinicians believe that they already know everything, after having diagnosed many living patients. This is why computer tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are being planned as future alternatives to autopsies. “We believe that relatives would tend to agree to such a non-invasive imaging process, instead of an autopsy in which the corpse is cut up”, says Wolf-Dieter Zech, a forensic pathologist at the Institute of Forensic Medicine of the University of Bern. In the coming years, he wants to assess whether post-mortem imaging can provide reliable information. To this end, deceased patients will be given a CT or MRI scan before an autopsy. Radiologists will make a diagnosis using the images, without any knowledge of the patient’s medical history. Zech will then compare their results with those of the traditional autopsies.

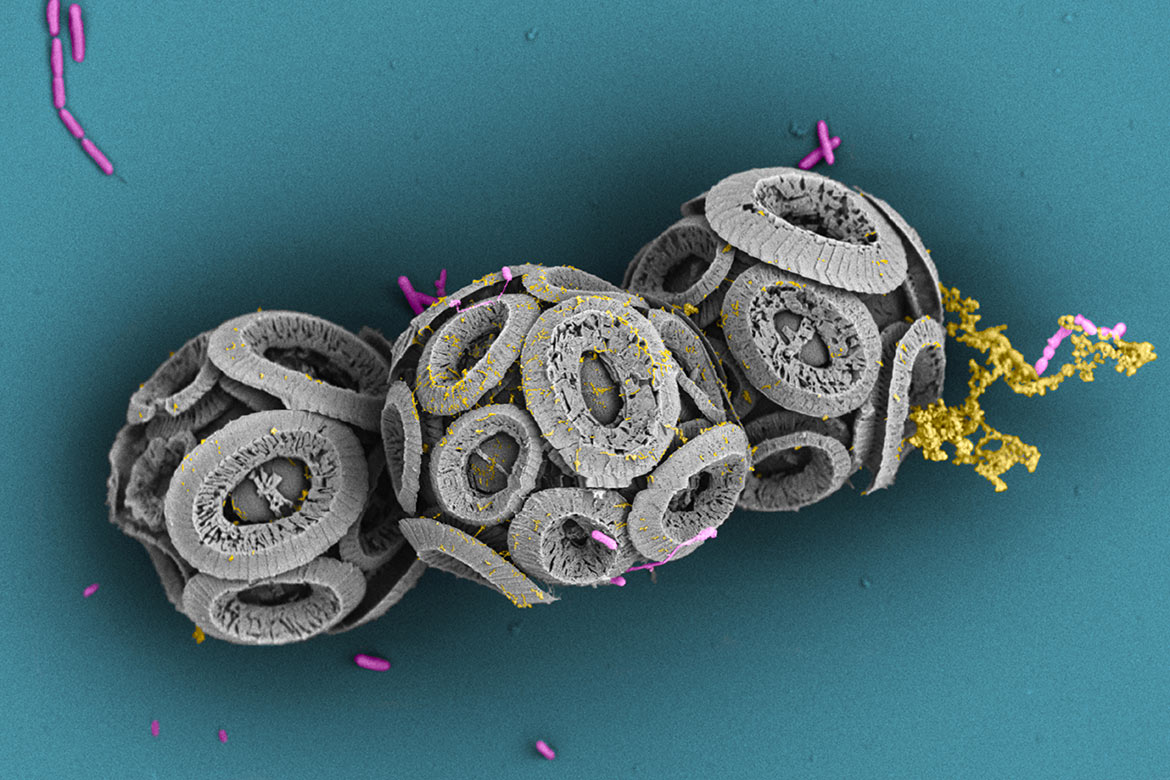

Previously, examinations have shown that frequent findings such as heart attacks, tumours and inflammation can be identified accurately using post-mortem imagining. In an autopsy, pathologists recognise a heart attack from the altered colour and consistency of the tissue of the heart muscle. On an MRI image, the changes in the damaged heart muscle are shown as different shades of grey.

A need for special training

Eva Scheurer is also convinced of the potential of post-mortem imaging. She is a physicist, a specialist in forensic medicine, and the director of the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the University of Basel. “After death, several things change in the body, which has an impact on how it is depicted on an MRI. That’s why you have to adapt the protocols accordingly”. For example, the contrast on an MRI is very dependent on body temperature, which is naturally much lower in a corpse. Because of this, Scheurer is now carrying out a study of how to depict the deceased brain using MRI.

There is a further advantage to imaging processes: digital images can be coordinated centrally and evaluated by specially trained radiologists. “In this way, the information loss caused by the drastic reduction in autopsies could be remedied at least in part”, says Zech. Scheurer is of the same opinion: “The autopsy is the gold standard and that isn’t going to change. But ultimately, a post-mortem MRI is still better than no autopsy at all”.