Martina Hirayama: “Switzerland is going to have its work cut out”

Martina Hirayama was appointed State Secretary for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI) in January 2019. She used to be a chemistry professor; now she wants to convince the Swiss universities of the future path they’ll have to take. Horizons wanted to find out more.

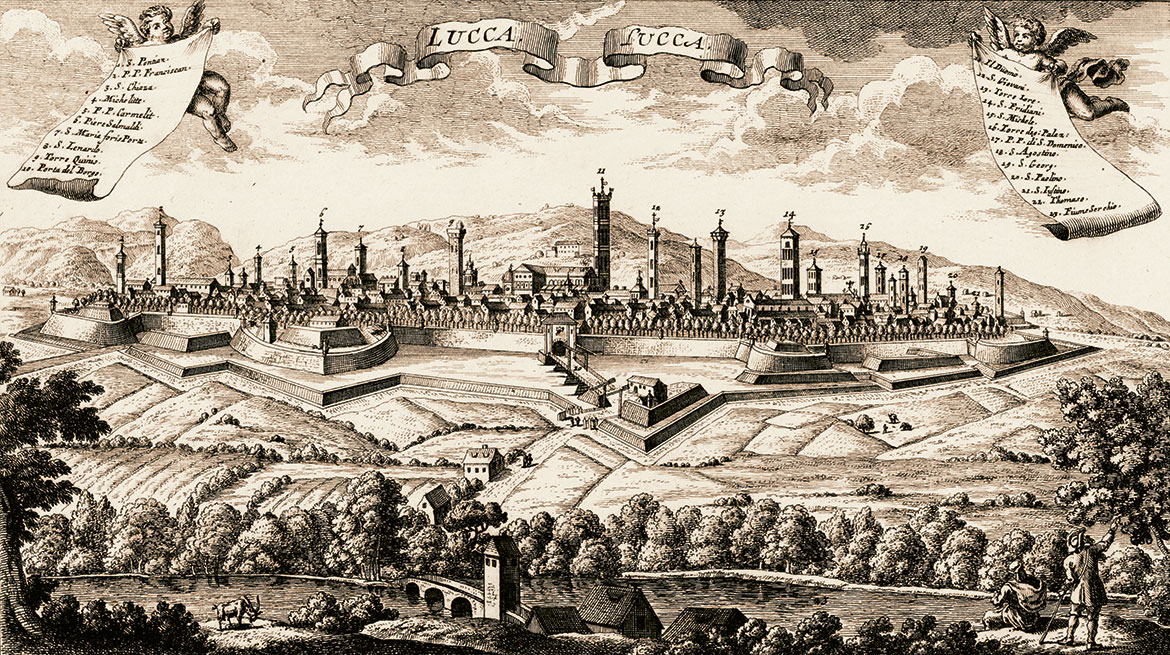

Getting the priorities right on the Swiss research scene requires careful foresight, says Martina Hirayama, the new State Secretary for Education, Research and Innovation. | Picture: Keystone/Peter Klaunzer

You swapped your professorship in chemistry for a position in administration. Was research too boring?

I found my research fascinating, but I was always interested in many different things and open to what was new. It’s also appealing to be able to have an impact on the framework conditions in the fields of education, research and innovation. Furthermore, even before I started work at SERI, I didn’t spend every day in the lab, but was primarily busy with my tasks as dean of the School of Engineering at the Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW). So leaving research was a gradual process.

The energy transition, digitalisation and antibiotic resistance: politicians are assigning an increasing number of priorities to science. Shouldn’t scientists and researchers be able to determine their own priorities?

The autonomy of researchers to decide their own focus areas is naturally important. But the universities have to decide what professorial chairs they want to create. The SERI is trying to address all the current challenges in a very general fashion. We’re asking: what do the universities want to focus on? Where do they want to collaborate – perhaps supported by project-based funds from the Swiss University Conference? [Ed. the federal umbrella body for the Swiss universities.] We need to have strategic goals for the different levels of the Swiss university system.

But the universities won’t want to be dictated to by the SERI.

We’re not doing that at all! Of course the universities have to recognise the point of collaboration in order for it to function. So we ask questions such as: How are we going to position ourselves in the field of quantum physics, compared to China with its ambitious policies? We have to ensure that the universities can have time to reflect on things. Otherwise, self-reflection gets lost in the everyday hurly-burly.

You come from the applied sciences – you’ve worked at ZHAW, Innosuisse, and you’ve been involved in start-ups. Do you see education and fundamental research primarily as aids to innovation?

Not at all! Research is about asking questions. The most important result you can get is an increase in knowledge. Some findings are simply not as directly ‘useful’ as others. But if there is an opportunity to apply knowledge, you should certainly grasp it.

Universities of applied sciences are striving to adopt the model of the ‘traditional’ university. For example, they want to be able to award doctorates. Wouldn’t this dilute their successful, practice-oriented profile?

In their position paper of 2014, the universities of applied sciences clearly stated that they want to award doctorates in cooperation with the traditional universities. The position of the federal authorities is also clear: the universities of applied sciences belong to the vocational career path, they are practice-oriented and their standard degree is the bachelor. But we are selectively supporting collaborations between the two types of tertiary institution.

They would also like to get more money for basic research from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Funding for basic research by the SNSF is primarily focussed on the traditional universities. But at the same time, the SNSF has application-oriented programmes such as Bridge. This is run together with Innosuisse, whose own primary focus is on application-oriented research. These two complementary funding institutions play an important role in the development of both our types of tertiary institution.

Innosuisse was recently subjected to strong criticism. It’s the successor organisation to the former Commission for Technology and Innovation (CTI), but people claim that this revamp has brought about a massive rise in administration costs, while useful networks have been downsized and decision-making has become more ponderous. Is that true?

Newly created organisations have their teething problems. We know about them in the case of Innosuisse, and we are working on it.

Israel and South Korea both invest considerably more money in research and development than Switzerland, when measured against their GDP. Shouldn’t we follow suit?

Switzerland is in third place, and it’s already very well positioned. And finances are only one factor. The framework conditions have to be in order if companies are to continue making large investments in research and development. So we need to have a sensible tax burden, a low degree of regulation density, peaceful industrial relations, and good infrastructure.

At present [Ed. in July 2019], things don’t look good for the framework agreement with the European Union (EU). Will researchers have to pay the price, just like they did when the mass immigration initiative was accepted?

We have to keep these things separate. There is no legal connection between the institutional framework agreement and the research agreement. When the mass immigration initiative was accepted, however, it affected the bilateral treaties. So the situation is different today. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that the EU will want to establish a political link between these agreements. At present, a lot of things are still open. But we know that our European partners appreciate us a lot.

Swiss universities are very successful internationally, which brings more and more foreign doctoral students to Switzerland. Do we need a ‘Swiss quota’ to limit foreigners, promote local talent, and maintain a national perspective?

The fact that we generate so much international interest is a good sign. It’s not the task of the federal authorities to prescribe who is allowed to study what. Every university should be able to determine these matters themselves.

Shouldn’t we do more to support the younger generation of Swiss researchers?

What’s important is that we have a good, dual education system that gives people freedom of choice. We have permeable structures for different career paths – that’s a big point in Switzerland’s favour. All students have to decide for themselves whether they are interested enough to want to do a PhD … after all, there are also very good jobs in the business world.

Your predecessors each spent roughly ten years in the job. What would you like to have achieved by 2029 in order to look back contentedly on the ‘Hirayama era’?

I hope we shall continue to utilise our opportunities to further Switzerland as a hub of research and innovation, and to help shape the processes of global change. Setting the right priorities requires foresight, a steady hand and close collaboration among the cantons, the universities, the funding organisations and the world of work. Maintaining our international position will be challenging, however, because the world is changing very quickly. There is immense competition. If we are in as good a position in ten years’ time as we are today, then we can be more than content. But to maintain this, we’re going to have our work cut out.