Feature: Better cities

City life sets you free

In the Late Middle Ages, the cities of Europe became large-scale urban centres. There, even non-aristocrats were able to climb the social ladder. A brief history of early urbanisation.

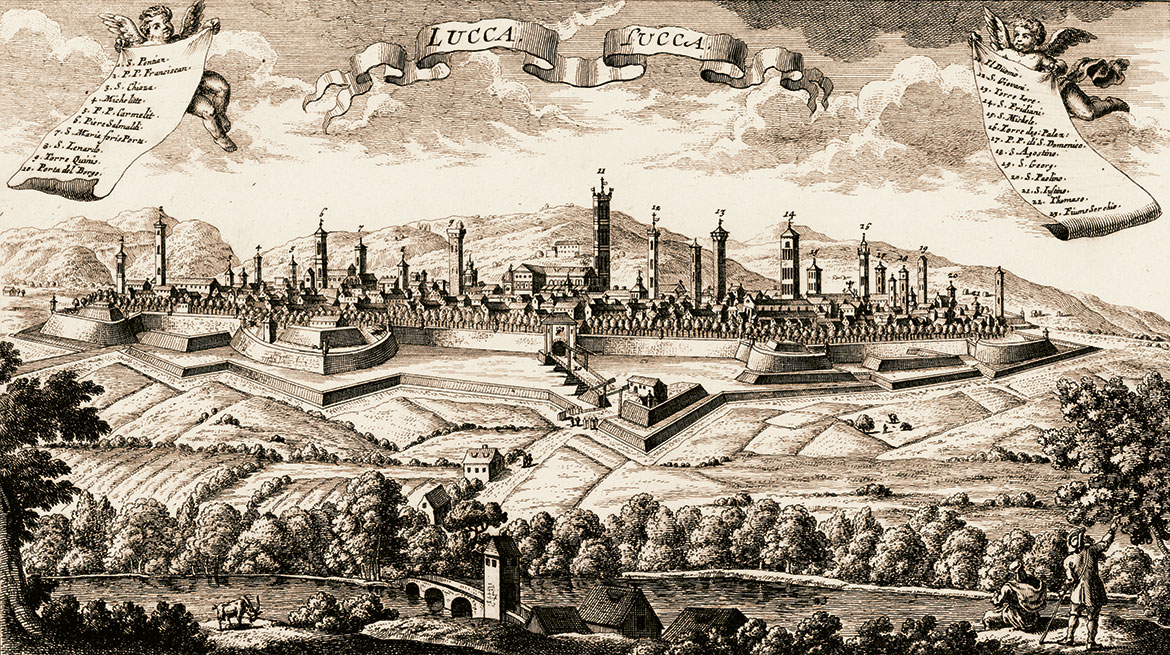

A copper engraving of Lucca in the year 1750: from the late Middle Ages to the present day, this Tuscan town has been defended by a city wall. | Image: akg-images

Whether it’s Paris, London, Cologne, Milan, Strasbourg or Basel – almost all of Europe’s prominent cities originated in urban structures of the ancient Roman Empire. Imperial Rome had turned Europe into a dense network of urban centres that helped it to maintain and administer its massive empire, and also served as showpieces of Roman civilisation.

Most of these centres dwindled after its downfall in the late 5th century, and few traces remained of them north of the Alps. But they nevertheless served as focal points for the great wave of urbanisation that swept Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries.

Freedom from feudal lords

The cities of northern Italy developed especially rapidly – e.g., Florence, Venice, Milan, Siena and Lucca. There, the urban traditions of Antiquity had remained largely unbroken, there was a prosperous trade in goods from the Orient, and rich merchants, bankers and craftsmen were able to acquire more and more rights from their bishops and aristocratic overlords. By the 11th century, for example, the citizens of the Tuscan city of Lucca were already being allowed to set up their own parliament and to stand for election to the city council.

Soon, the rich merchant families took the reins of the city. In 1160 the Tuscan margrave even gave Lucca dominion over the surrounding region in return for an annual tribute: the so-called ‘Contado’. The local nobles were forced to hand over their country residences and settle in the city. Lucca then advanced to become an independent city-state with its own legal system offering its people protection and legal security. This in turn provided a major boost to its economic ascent.

It was not just in northern Italy that these new rights became important. In France, Germany and Switzerland, too, cities were able to establish themselves as independent legal spaces in the course of the late Middle Ages. Simon Teuscher, a professor of mediaeval history at the University of Zurich, regards this development as part of a ‘spatialisation of rights’ in which rights and duties began to be detached from people and linked instead to territorial structures. ‘Luft macht eigen’ (‘air brings bondage’) was a German proverb at the time, meaning that if you lived on a piece of land – and thus breathed its air – then you belonged to the lord of that land. The later expression ‘Stadtluft macht frei’ (‘city air makes you free’) was derived from this, and referred to the law – applied in many places – according to which a peasant or a maid who had escaped from their feudal lord could no longer be reclaimed by him once they had spent ‘a year and a day’ in the city.

These ‘escapees’ were now subject to the city’s laws, which granted them more personal rights than before. They were also freed from duties like paying inheritance tax to their lord. Men benefitted especially from the rights accorded by a city. As long as they had the necessary financial means, they could even acquire citizenship and all the comprehensive rights that came with it. This was something that women were denied, however.

“The city, as a newly established legal space, exerted a powerful pull on people”, says Martina Stercken, also a professor of mediaeval history at the University of Zurich. “Here, even non-aristocrats enjoyed the opportunity to move ahead and to climb up the social hierarchy”. It is interesting to note that most cities in Central and Eastern Europe were founded between the 12th and 14th centuries by members of the clerical and secular nobility. This enabled them to maintain their power, expand their influence, and profit from the growing urban economy.

In many places, this development became visible through the construction of a city wall or other fortifications. It meant the city separated itself from its surroundings, and demonstrated its ability to defend itself, either against the nobility based out in the countryside or – as in the case of Italy – against neighbouring, competing cities. Today, little remains of these sometime symbols of a free, self-confident citizenship, because most fortifications were demolished in the 19th century. It’s in Lucca that we still find what are probably the best-preserved, most beautiful city fortifications in Europe. Its ringed wall is 4.2 km long and now boasts a continuous, green walkway that makes a significant contribution to what is the city’s most important economic sector today: tourism.