Feature: Better cities

Is there really a chasm between town and country?

The Swiss tend to assume that urban and country lifestyles are two separate entities. We’ve gone hunting for this Great Divide.

A car-free suburb with urban charm, surrounded by mountains. In Uptown Mels, the ideal features of city and countryside come together. | Image: Michel Bonvin

Since the 1990s, the supposed urban-rural divide has been a recurring topic in Switzerland – especially on voting days. In mid-June 2021, the Swiss electorate rejected a proposed revision to the CO2 law on restricting greenhouse gas emissions. This prompted Michael Hermann, a political geographer and the head of the Sotomo research centre, to declare to the media that “the divide is getting deeper and deeper”. The big cities had accepted the law by a clear margin, while most rural areas were against it. This pattern is typical of the close outcomes in referenda over the past 30 years, though there have been victories for both sides.

Hermann has been studying the political divide between town and country for 20 years. Using national voting results, Sotomo has identified a geographical shift that took place between 1990 and 2018. With the exception of Lugano, the big cities moved politically to the left. This was most conspicuous in the case of Bern, the administrative centre of the country, which moved from a centrist position to being the one situated the farthest to the left in Switzerland. The neighbouring agglomerations shifted to a significantly smaller degree, while the rural areas remained conservative.

In December 2021, Sotomo completed a new study that diagnosed a “massive widening of the political divide between towns and the countryside”. In 14 out of the 22 national referenda of the current legislative period, a difference has opened up between the big cities and the rural areas that is, according to Sotomo, “far greater than the long-term average”.

The wolf and the car

Markus Freitag is a professor of political sociology at the University of Bern. He confirms that surveys conducted in Switzerland over the past few decades have revealed clearly identifiable differences in attitude between the countryside and the city. All the same, he believes that these two poles are neither moving closer to each other, nor drifting apart. According to these surveys, people in the city have a more positive attitude towards the welfare state, dismantling the army, political openness and wild animals, while people in the countryside have a more negative attitude to all of these. What is striking is their attitudes towards the car, which is seen as positive in the countryside but negative in the city. It is exactly the opposite with the wolf: city-dwellers regard it as part of the romance of Nature, while people in the countryside see it as a problem. “The car is to the countryside what the wolf is to the city”, says Freitag.

Since early 2021, Freitag’s research team has been participating in the three-year EU project ‘Rude’ (‘Rural-Urban Divide in Europe’) along with groups from the universities of Barcelona, Grenoble, Glasgow and Frankfurt. Their tasks include conducting research into how the urban-rural divide affects political and social convictions in the context of globalisation. When compared to other countries, this divide is especially visible in Switzerland in questions of political openness.

However, Switzerland’s political and economic structures are helping to defuse this conflict. The short distances involved, along with instruments of the State, e.g., revenue sharing and the education system, all help to prevent remote areas from being cut off economically. There can be no comparison here with the USA, for example, where there are two fiercely competitive political parties that actively play on the divide between city and countryside, or with France, where the centralisation focused on Paris exacerbates such differences.

Freitag points out that almost four million people (i.e., 45 percent of the population) live in conurbations in Switzerland (though this admittedly depends on your chosen definition of ‘conurbation’), and that these heterogeneous, intermediate areas have been subjected to little research up to now. He is fascinated as to why people who live in urbanised agglomerations that are architecturally similar nevertheless display attitudes that mirror the urban/rural pattern. “It is astonishing, but even people living close to the city boundaries often describe themselves as not being city-dwellers”. Researchers have not yet identified just where these transitions occur in the conurbations.

Scepticism towards new construction

But where does the city end and the countryside begin? In statistical terms, the distinction is clear: there are some 170 towns or cities in Switzerland. The Federal Statistical Office defines these as “contiguous core zones with a high population and workplace density” and with at least 12,000 total inhabitants, employees and overnight guests (the latter being especially relevant to tourist resorts). Zurich is at the top, although the list also includes Buchs (St. Gallen), Zermatt and Ecublens (Vaud).

By contrast, researchers define a city as a combination of several levels. In physical terms, a city is characterised by dense land development and by the existence of central functions. But there is also a social level and a symbolic level in which a city is understood as a place of specific experiences, options, conflicts and encounters – e.g., with communities of foreign immigrants, pop-up restaurants or squats. Altogether, this can be termed ‘the state of being urban’.

David Kaufmann is an assistant professor of spatial development and urban policy at ETH Zurich and the Deputy Head of its ‘Network City and Landscape’ (NSL). In the researcher’s definition of the city, he discerns something that is characteristic of Switzerland, which is “urbanised over a large area, but not very intensively”. There are no huge cities here, but “many individual urbanisation processes that can be intensive, both in the centres and in the agglomerations”.

Kaufmann is currently investigating the degree of acceptance for densification projects in the Swiss cities. The population has frequently expressed resistance to urban densification. Could this be an expression of a desire to preserve a ‘village-like’ character in the city? Kaufmann disagrees, and believes that it actually has more to do with a general scepticism towards the changes to the cityscape that result from new construction projects. The connections here are complex, he says. The positive effects of densification – e.g., less urban sprawl – are observable in the long-term and on a large scale, while the constructional changes involved directly affect the people on the spot in the short-term.

Mutual colonisation

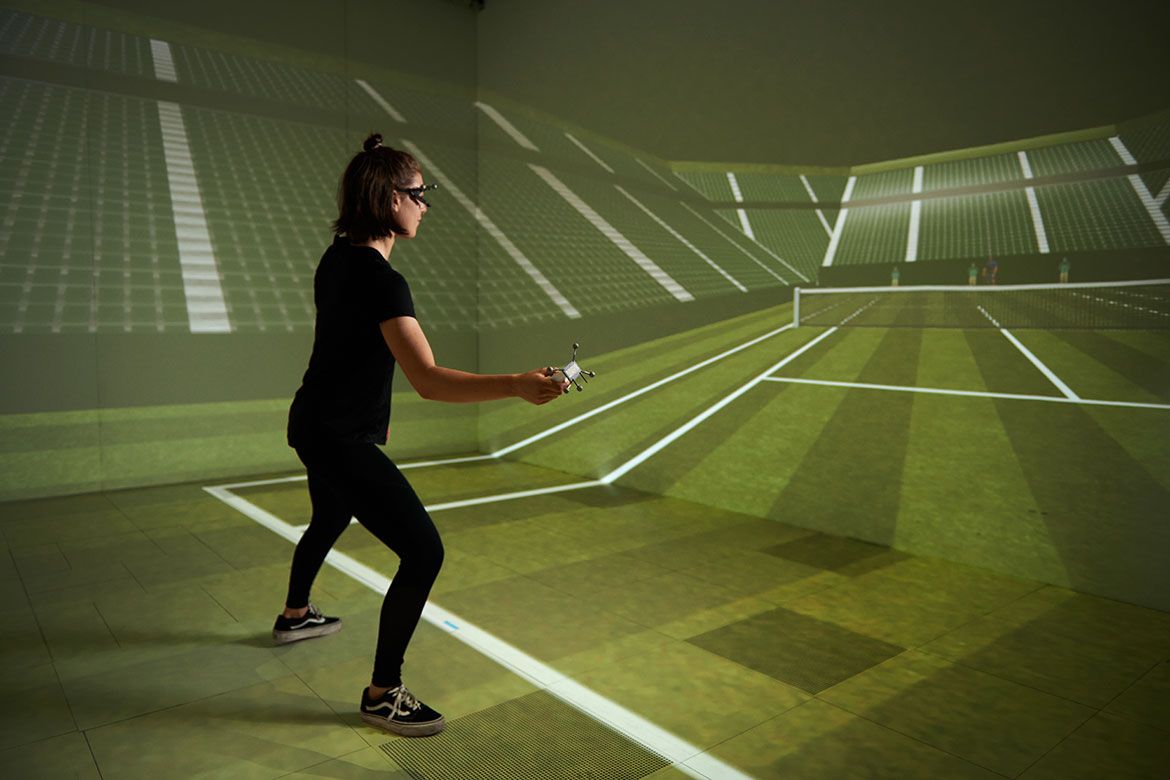

Vincent Kaufmann, an associate professor of urban sociology and mobility at EPFL, uses a metaphor to explain why Switzerland’s urban zones are not very densely built: “When faced with a physical obstacle, we Swiss like to build a tunnel”. In other words, the continuous expansion of transport infrastructure in Switzerland has turned it into a country of commuters across an extensive urban landscape that stretches from one end to the other – from Geneva in the south-west to Romanshorn in the north-east.

Nine out of ten jobs in Switzerland are now located in the urban centres, he says, and urban lifestyles are extending into its farthest corners. “Actually”, he says, “we’re experiencing a kind of mutual process of colonisation”. It is not a problem to live in a village in the canton of Jura while working in the centre of Geneva – especially since the pandemic raised the degree of acceptance for working from home and teleworking. But he also points out that it’s not clear just what this means for people’s feelings of being rooted in a place.

“I think that the idea of an urban-rural divide is outdated”, says Heike Mayer, a professor of economic geography at the University of Bern. “In fact”, she says, “the extremes are geographically close to each other”. She points out that peripheral regions such as the Lower Engadine or the Emmental are actually home to dynamic, innovative companies that are producing for the world market. And conversely, zones of temporary stasis can be found in urban areas, like industrial wastelands on the outskirts of cities.

Mayer has found interesting pointers in the work of one of her doctoral students. He is studying multilocal forms of work, following men and women who divide up their working week between office days in the city and teleworking in the mountains. He found a pattern emerging in which people use the city and countryside to complement each other. They go to the city for the creative side of their work – the side that needs a lot of personal meetings. And they reserve the mountains for the side of their work that requires concentration and privacy. Mayer believes that this is also an indication “that we should devote more energy to understanding the city and the countryside not as opposites, but as aspects of a complementary system”.

There is no doubt about it: the divide between town and country indeed exists in people’s minds and sometimes finds expression in the way they vote. But in the everyday life of most Swiss people, the city and the countryside flow one into the other so that it is almost impossible to tell them apart.