As if drawn by machine

Creativity and individuality are children of our time. In the 1940s students of graphic design were trained to lose their own style. Their goal was essentially to mimic machine production.

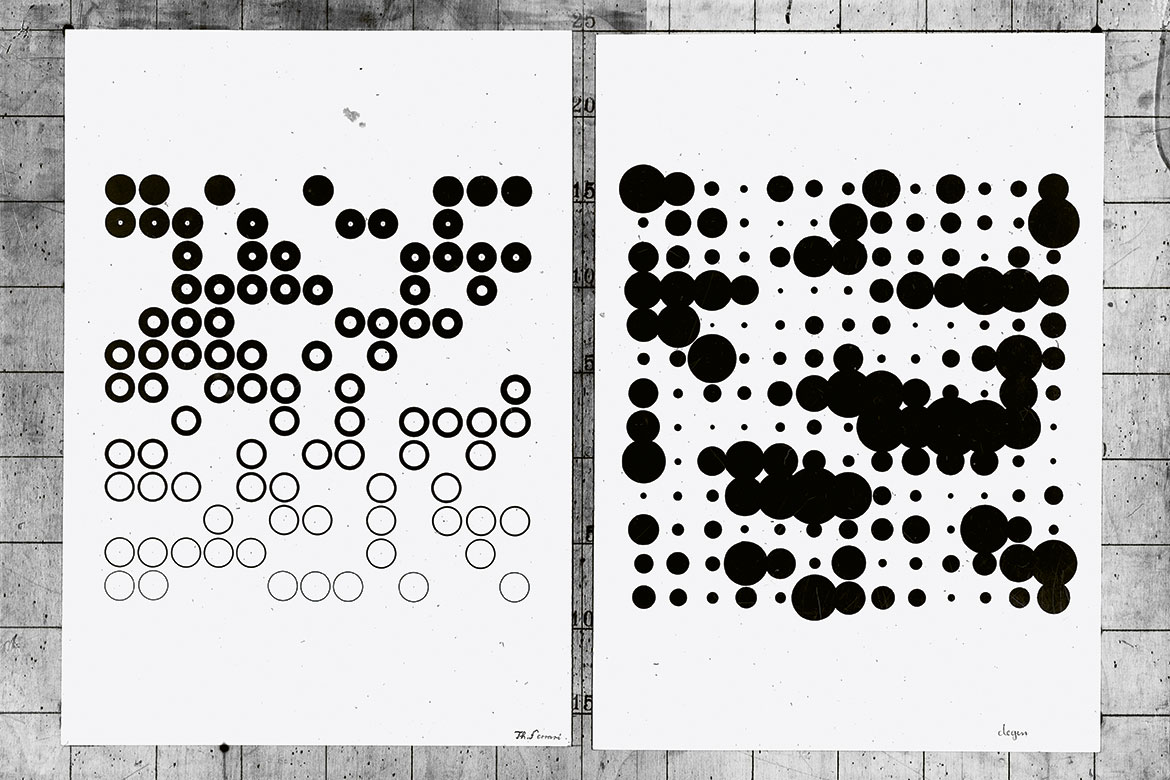

Image: A reproduction of two pieces of work by students: Theo Ferrari (left) and Degen (right) from Hermann Eidenbenz’s class on ‘Preparatory drawing’ in the handicrafts department of the Allgemeine Gewerbeschule (the ‘general crafts school’) in Basel, ca 1941. Copyright Mathias Eidenbenz.

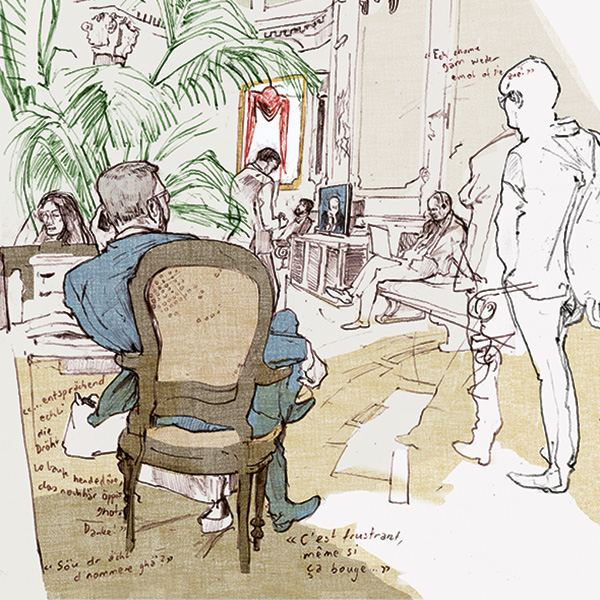

Pictures drawn by artificial intelligence are already being sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars. Self-learning machines are drawing works that in some cases are unsettling, and don’t come across as if drawn by a machine. By contrast, the graphic motifs reproduced here look as if they could come from a computer game of the 1990s, or are perhaps the result of algorithmic data processing.

The truth is very different. These drawings were made in the 1940s by trainees in the graphic design class in Basel, using drawing pens and ink, all as part of a subject entitled ‘Preparatory drawing’. Their story proves that we would be well advised to question the myth of uniqueness that seems generally inherent to the history of Swiss Graphic Design. These motifs were drawn as part of a primarily technical exercise, says Sarah Klein, a historian of graphic design. “There are several almost identical originals, but with different signatures. They adhered strictly to their model and copied out the same motifs time and again by hand”. Klein is currently working on her doctorate, and came across these papers in the archives of the graphic design teacher Hermann Eidenbenz. Initially, she was “disappointed about the lack of design freedom”. But then this very fact became the object of her research.

Robert Lzicar works at the Bern University of the Arts HKB and is the co-coordinator of its research project into Swiss Graphic Design. He well knows why the training back then involved so little creativity: “The purpose was to establish a demarcation line between the graphic designer and the artist; it was about getting designers to erase their own style. They tried to standardise things, and to renounce what was ‘human’. They were essentially trying to train people to be robots”. In the course of his research, Lzicar has spoken with people who did that very training back then. “Every time their own style shone through, they had to start their task all over again. They quite specifically practised being able to produce like machines”.

Similar practice motifs were used internationally, says Lzicar, and there was a lot of exchange between schools. This fact also seems to contradict the myth of Swiss Graphic Design as something unique. Lzicar is adamant: “We have to call this myth into question”.