Portrait

The two worlds of the author Anna Stern

When she writes, she researches too – the microbiologist Anna Bischofberger, a.k.a. the author Anna Stern, won the 2020 Swiss Book Prize. She needs both worlds – research and fiction.

Creativity is important to Anna Bischofberger, both in her experimental research and when writing fiction. | Photo: Ornella Cacace

The past year has been a rollercoaster for Anna Bischofberger. The lockdown in March 2020 meant she was unable to complete the final experiment for her second doctoral project in microbiology, because all experimental research in the laboratories of ETH Zurich was halted. But this downer was followed by a real high that was equally unexpected: under her writing name ‘Anna Stern’ she won the Swiss Book Prize in November 2020 with her latest novel. “I knew that my book was coming out in the autumn and was really looking forward to it. The nomination for the Prize triggered mixed emotions. I was pleased about the recognition, though I also asked myself: How can I reconcile this with my research?”. But she assumed that the hullaballoo would soon be over, once someone else won the prize, and then she would be able to concentrate on her doctorate again. That’s not how things turned out.

Discipline, holidays, and precise planning

The second wave of Covid-19 was already in full swing when this 30-year-old author from eastern Switzerland was announced as the surprise winner of the Swiss Book Prize. A lot of the events connected with the Prize were cancelled, or shunted into the virtual realm. “That made things easier to organise. But happiness is something that you can only enjoy to the full when you share it”. She’s someone who likes to work, and that’s why she manages to devote herself to two different passions at the same time, she says. She likes going on holiday alone, and writes a lot when she’s away. “But I also really like to plan things very precisely”, says Bischofberger. And yet it takes more than precise planning and discipline to be able to do well in two highly demanding worlds. Bischofberger is also able to rely on support from her doctoral supervisor, Alex Hall, who offered her an 80-percent post because he knew how important it is to her to write.

For a long time at school, Bischofberger did not take any of the natural sciences. “The more I postponed taking them, the bigger my fear grew with regard to them, because I always thought: ‘I can’t do them anyway’”. Ultimately, it was a teacher at grammar school who raised her enthusiasm about them. And so, after several detours through other subjects, she finally landed in the environmental and natural sciences. What particularly appealed to her about this field was the fact that it always links the natural sciences with societal issues.

Am I also my bacteria?

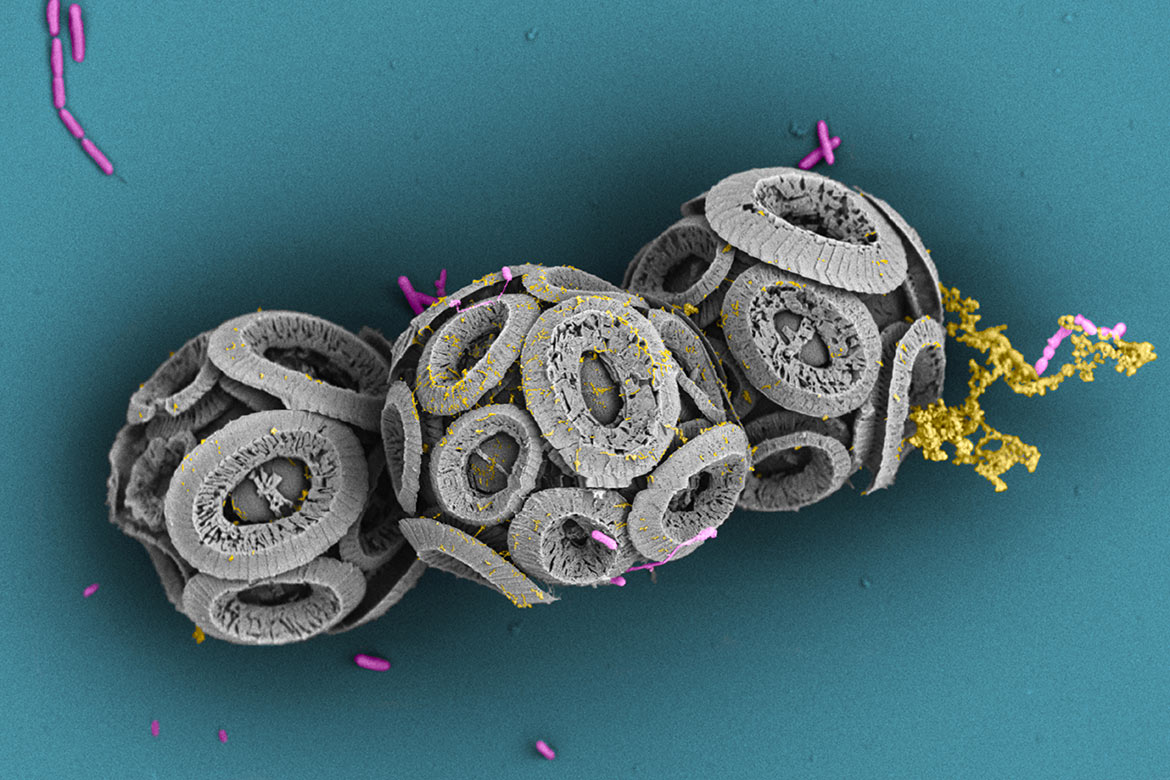

The same can also be said about her current research project. Bischofberger is investigating whether the bacteria E. coli can develop resistance to the antimicrobial effect of honey, and is trying to determine what mechanisms might play a role in this. She has been able to identify one such mechanism that makes E. coli noticeably less susceptible to the honey types she has looked at. “To our knowledge it’s the first time that anyone has proved a connection between a specific group of genes and an increased resistance to honey”. But so far, she “hasn’t found the point beyond which the bacteria would no longer be treatable with the honey products we’ve investigated”.

Bischofberger explains that in the 80 years in which we’ve been using antibiotics, we’ve failed to do two things: We haven’t been researching into new active substances, nor have we investigated what happens if we use these drugs on a broad scale. “This is what we’re now trying to find out in retrospect, as it were: What environmental factors influence resistance?”. In her next project, Bischofberger would like to find out more about the human microbiome. “In my literary texts, I often deal with the individual self: Who am I? How can I set myself apart from my environment?”. She believes that researching into the microbiome leads to similar questions: “Am I just my cells? Or am I all of my microbes? How can I do something good for them? And if I do, am I also doing something good for myself?”.

Writing as another kind of research

Relationships between people are also essential to Bischofberger. That becomes clear in her literary texts, in her statements on important role models in her career, and when she explains how she is delighted when researchers from her team attend her readings. “In science, I’ve learnt that the only work that counts is what I deliver in the laboratory. As a human being, however, I have different needs”. In literary circles, she has already been asked if she wouldn’t prefer to concentrate on just one field in order to become better and better at it. “But it’s not my goal to be the first at anything; I just want to be able to do what I like doing”.

Bischofberger has no problem finding the words to explain what links science and writing. “In experimental research, creativity is very important. I can’t just replicate what has already been done. I have to take existing work and combine it in a new way so that the results show something new. It’s similar with writing. I can’t just copy a book by Max Frisch and sell it as my own afterwards”. In her prize-winning novel, Bischofberger engages in several experiments at once. One is that none of the characters in her novel has a specific gender. She doesn’t like it when we try to understand the feelings, thoughts and actions of people by means of categories.

The courage you need when you don’t always know what’s going to happen, combined with curiosity towards what then actually happens: this is the mixture that determines both of Bischofberger’s two ‘lives’. “When you do research, you want to discover something that no one before you has ever observed”, she says. “To me, writing is another form of research. Both begin with an observation that I can’t categorise. Writing is like seeking a way to cope with that”. Neither is about presenting unambiguous solutions. “At the end, perhaps there’ll just be a new question”. In her current book, Bischofberger tries to find a way to deal with loss: a group of young people are grieving over the death of someone they loved. “The fact that a text has emerged from this gives a certain meaning to what one experiences”.

Bischofberger listens intently during our conversation and doesn’t forget any part of the questions put to her. She enjoys the attention that she is receiving from the public as ‘Anna Stern’, but only “as long as it’s focused on what I do. It’s my book that was given a prize, not me as a person. Every book always includes a lot of work by other people”. And where does she see her career progressing from here? The pandemic has made her usual, precise planning impossible, and the book prize has in any case changed everything. So her priority at the moment, she says, is simply finishing her doctorate. “I would like to give myself the freedom not to choose what comes afterwards – not yet”.