ALTRUISM

Nothing’s for free

Ants toil away for their queen. Rats divide tasty morsels among themselves. And fish offer escort protection. Animals often seem to act selflessly. But why they do it remains a matter of debate.

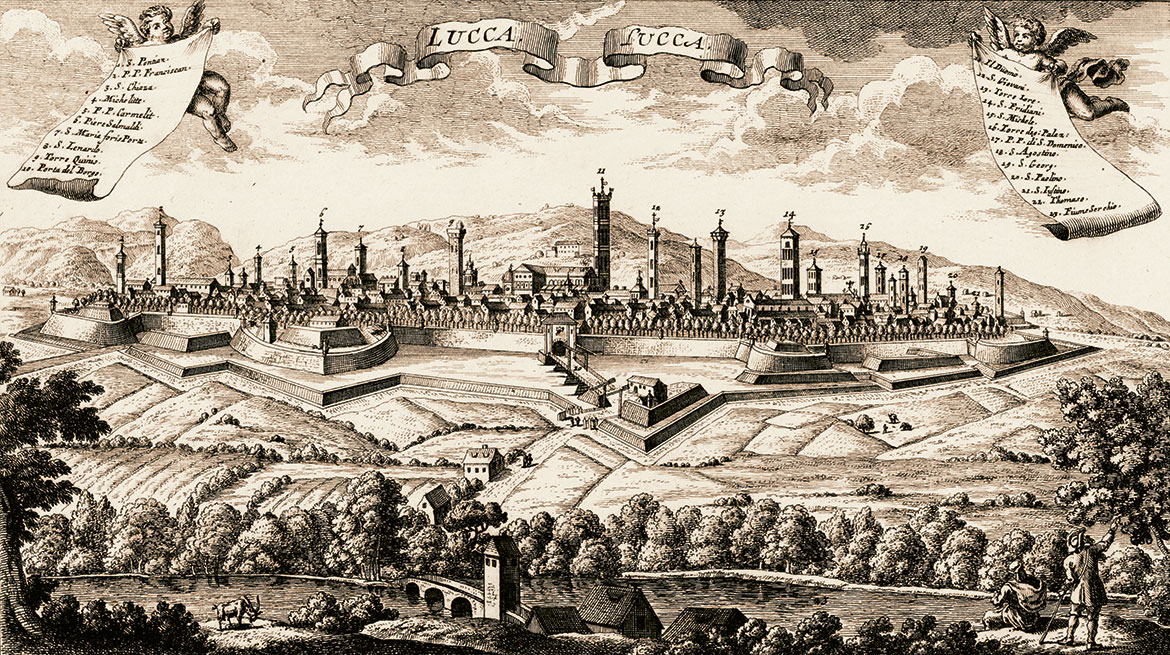

Cichlids defending their territory against intruders. Group members have to help the dominant couples raise their offspring, otherwise they are punished. | Image: Michael Taborsky

Evolution is relentless. Only those who survive and reproduce can pass on their genes. And so it is in Nature: every individual looks out for itself. Nevertheless, we often find a readiness to help others in the animal kingdom. Several hundred workers carry pollen to the nests of earth bumblebees in order to nourish the larvae of their queen. Young veiled eagles clean the plumage of their siblings and share their food. Guppy fish accompany fellow members of their species when they approach a predator, in order to determine how dangerous it is. So why do these animals all act in such an altruistic way?

“Because ultimately, they themselves benefit from this behaviour”, says Michael Taborsky, a behavioural biologist from the University of Bern. For 40 years now, he has been investigating cooperation and helpfulness in different animal species, such as brown rats. The social structures in which these animals live depend very much on their environment. In some places, a core family comprising a female and her young will occupy a small territory. In other places, up to 200 individuals – both related and non-related – will come together to form a kind of clan. They sleep in joint nests, clean each other’s coats, and exchange food.

Animals also help each other under laboratory conditions, as Taborsky and his colleagues have shown. They have taught rats to pull up a board that then lets a partner rat in the neighbouring compartment get a tasty morsel. But an animal will share such gifts only if it, too, can gain from being helpful – a principle that biologists call reciprocity (see the box ‘Altruistic? Really?’). The researchers discovered that once a rat has received a gift, it will act more generously in future towards all its conspecifics. But they also show signs of gratitude. Rats prefer to provide food for helpful fellow rats than for the scrooges among them. In one experiment, animals were given more food in return after having helped partner rats to get banana pieces instead of carrots. The rats may like carrots, but they adore bananas.

Cooperation smells good

The brown rats clearly remember exactly who has helped them before, and who hasn’t. Taborsky recently published the results of a study for which he and his team investigated rats who had met four fellow rats, one after the other. The test rats were given a tasty morsel by just one of the four others. When the roles were swapped around five days later, the test rats gave their generous fellow rat much more food than the others – roughly as much as they had themselves received. “We can thereby deduce that the animals take care not to be exploited by the egotistical rats among their peers”, says Taborsky.

This is the only way in which they can explain bartering behaviour among the rats. The animals are helped in this by their good memory – and their sense of smell. The researchers from Bern have also recently found out that brown rats can smell whether or not their opposite number is cooperative or stingy. “We still don’t know how this smell is created”, says Taborsky. “But it is probably a so-called honest signal that rats cannot manipulate”.

Out in the wild, the conditions for cooperation are not always as fair as in laboratory experiments. Taborsky is also investigating the social behaviour of the daffodil cichlid (Neolamprologus pulcher) whose home is in Lake Tanganyika in East Africa. A dominant breeding pair will be supported by members of their group when rearing their larvae and fry. “If such a helper fish doesn’t really help, then it’s bitten or rammed by the others, and in a worst-case scenario expelled from the group”, says Taborsky. And daffodil cichlids won’t survive long on their own. “The subordinate fish is thus compelled to work with the others”, says Taborsky. “In return, it does not become prey for predators”.

But as has been often documented, animals can also act selflessly (see the box ‘Altruistic? Really?’). In more than 900 species of birds, young birds sometimes refrain from founding their own families and instead help their parents to raise further broods. And for many insects, such as bees and wasps, whole colonies are established in such a way that only a single queen reproduces. Ants offer us a prime example of animals that are highly social in this way. Depending on their species, the ants of a colony can have up to more than a dozen different ‘job descriptions’. Some feed the larvae, some remove waste, and some go hunting for food. What they all have in common is that they never reproduce at any point in their lives. Nevertheless, there is never any revolt against the queen. “That is only possible because the ants in a single colony are all closely related to each other”, says Laurent Keller, an ant researcher at the University of Lausanne.

Altruism in the interests of the genes

In biology, the term for this is ‘kin selection’. Back in the 1960s, the British researcher William Hamilton recognised that an animal doesn’t have to reproduce in order to pass on its genes. In terms of evolutionary biology, it can also benefit if its relatives reproduce. For example, an animal shares half of its DNA with its sister. If helping its sister means she can bring up two more young than she would on her own, then this is of equal value to one offspring of its own.

In ant colonies, the workers are very closely related, and these animals are highly productive when they work together. “This is why altruism was able to develop so prominently among them”, says Keller. So in essence, ant workers are only superficially selfless. They help others because it means they can pass on more of their own genes to the next generation.

Superficial selflessness - or reciprocity?

For Keller, it’s obvious that kin selection is the driving force behind helping behaviour in the animal kingdom. In cases of reciprocity, this is usually the reason behind it; in cases of altruism: always. In most groups where we find cooperation, the individuals are more closely related than they would be if animals just happened to come together. This also helps to explain from an evolutionary standpoint how such a readiness to help emerged. “Birds, for example, will help their relatives to rear more young more often, but offer such services less frequently to non-relatives”.

Taborsky sees things a little differently, however. He says it’s beyond dispute that true altruism – such as in an ants’ nest – can only emerge among relations. But reciprocity exists even without any familial relationships. Rats are even more willing to help non-related animals – after all, this could increase their chances of getting something back in future. The condition of the recipient is also important. “A rat is much more generous towards hungry conspecifics”, says Taborsky. And they have good reason for acting thus: It’s more important to them, too, not to die of hunger, rather than to get ‘dessert’ when their stomach is already full.