Replicability

Non-replicable work is gaining more citations

Publications whose findings are not replicable are being cited up to 300 times more often. Could science be heading in the wrong direction?

Scientific papers with more ‘interesting’ findings receive greater attention than others. But whether or not they’re accurate is another matter entirely. | Photo: zVg

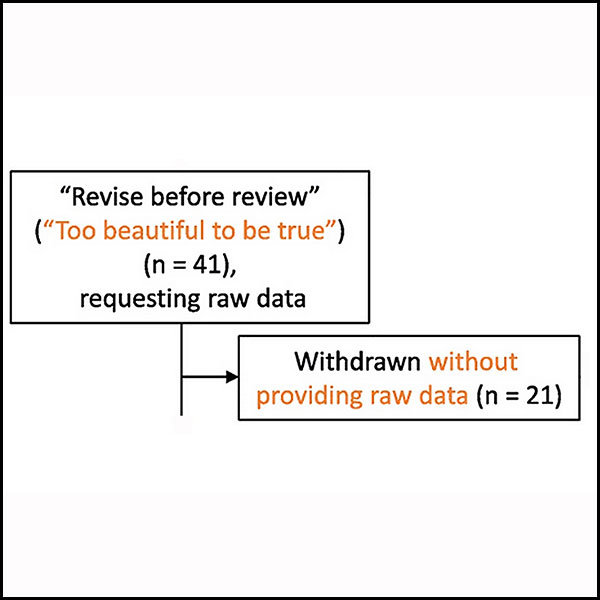

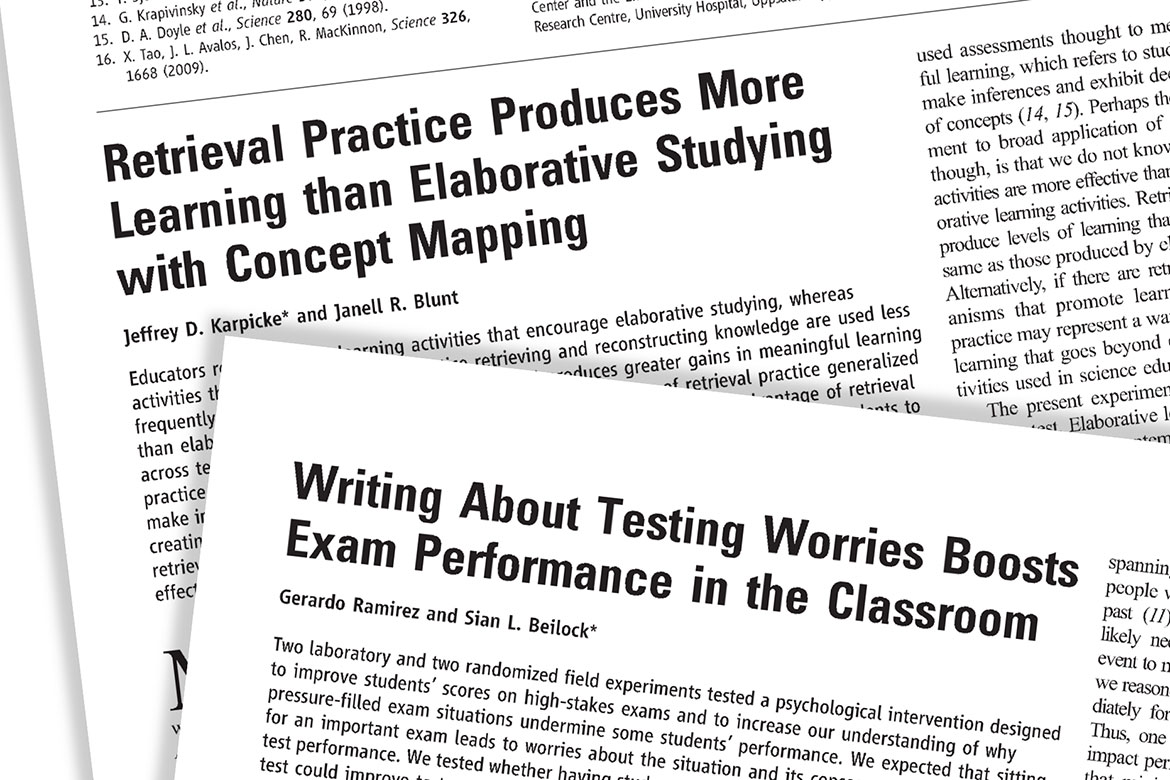

A new chapter is being written in the story of the replicability crisis. Two behavioural economists at the University of California have published an article about the fate of publications analysed by three influential replication projects in the fields of psychology, medicine and the social sciences. “Our main finding is that papers that fail to replicate are cited more than those that are replicable”, write Marta Serra-Garcia and Uri Gneezy in the specialist journal Science Advances. In fact, in the period investigated, non-replicable papers were cited over 150 times more often than papers whose findings had been proved to be replicable. With studies in the social sciences that were published in Science and Nature, the non-replicable papers typically got 300 more citations. What is remarkable is that only a minority of these publications – just 12 percent – acknowledge their failures after proof of their non-replicability has been published.

The two authors have reached a further unsettling conclusion: “Assuming more cited papers present more ‘interesting’ findings, a negative correlation between replicability and citation count could reflect a review process that is laxer when the results are more interesting”. The reproducibility expert Brian Nosek – who did not participate in the study published by Serra-Garcia and Gneezy – has even issued the following warning in The Guardian newspaper: “We presume that science is self-correcting. By that we mean that errors will happen regularly, but science roots out and removes those errors in the ongoing dialogue … If more replicable findings are less likely to be cited, it could suggest that science isn’t just failing to self-correct; it might be heading in the wrong direction”.