GENDER MEDICINE

How gender was forgotten

Man or woman? This question is crucial to issues of prevention, diagnosis and therapy, but is asked all-too-rarely in research. We consider why.

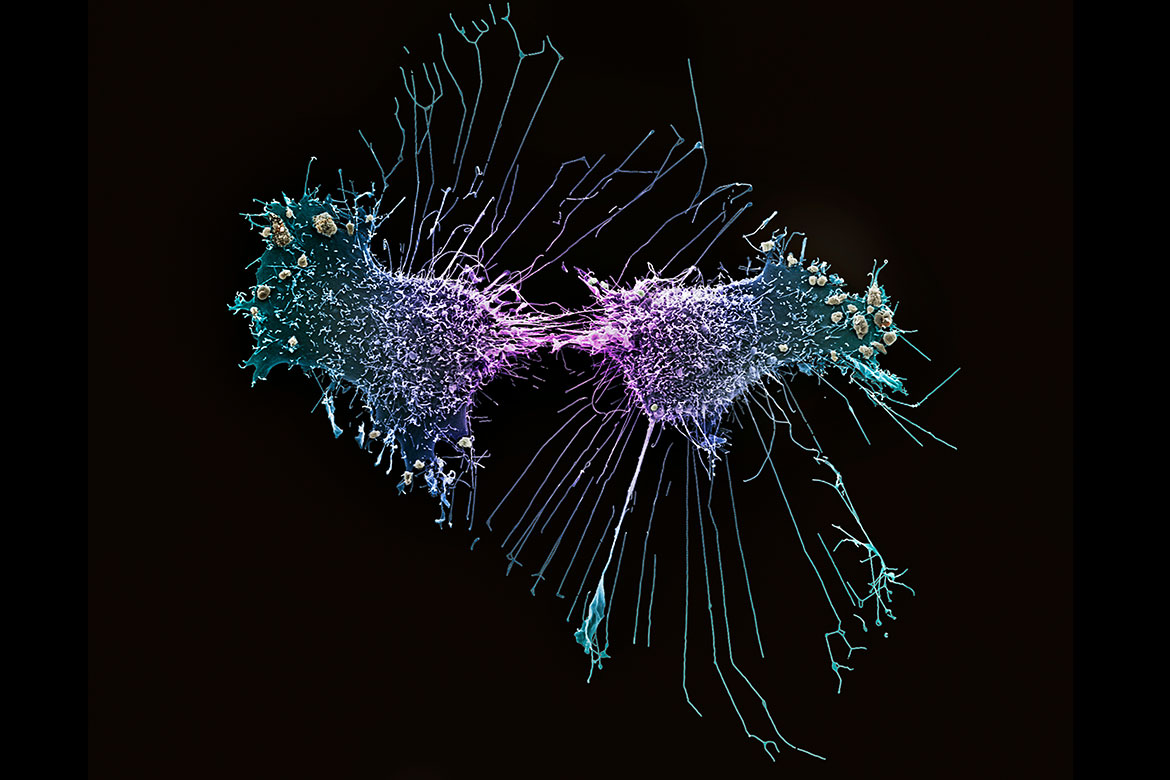

The so-called HeLa cells from 1951 are female. They were the first-ever cells able to divide and multiply outside the body and are still used in laboratories across the world today. They derive from the cervical cancer that killed Henrietta Lacks, an African-American woman. | Image: Anne Weston/The Francis Crick Institute/SPL/Keystone

Covid-19 is more likely to be fatal in men than in women. There are also gender differences when it comes to heart attacks, as they tend to manifest themselves in women through subtle signs such as back pain, but rarely through a pain radiating into the left arm as is common in men. And when women suffer from heart failure, they only need half the recommended dose of the most important class of drugs. Nevertheless, it is only in the last few years that the factor of gender has been taken into account more systematically in medicine – and it’s primarily women who have taken the lead in this.

A knowledge of gender medicine can also decide matters of life and death. A Swiss-wide study published in 2021 found that women are less likely than men to receive intensive care treatment for severe cardiovascular diseases – often because doctors do not assess their symptoms correctly. Conversely, osteoporosis and depression are often diagnosed too late in men, as they are considered typically ‘female’ ailments. For many diseases, social gender also plays an important role alongside biological gender. This is probably true for eating disorders, which affect more women than men, and for addictions, which affect more men.

Cells have a gender

To this day, gender plays only a very limited role in research and practice. If this is to improve, many areas will have to see a change in thinking. According to Carole Clair, the co-head of the Medicine and Gender Unit at the Centre for General University Medicine Unisanté in Lausanne, this rethink will have to start with basic research: “We need to carry out a systematic review of previous studies on the development of diseases to see if they differentiate between female and male cells, and between female and male animals”. She admits that not all diseases show any differences, but usually we know nothing at all about such issues because researchers have hardly ever asked about them.

Until now, studies have rarely revealed the gender of the cells or animals under investigation. This is a missed opportunity. More recent work, for example, has shown that receptors in female cells transmit pain signals more quickly. But around 80 percent of existing animal studies on pain perception and treatment have been conducted on male animals. So it is hardly surprising that gender medicine is critical of these studies, too. “Only when basic research starts to take gender-specific differences more into account will we in future be able to develop targeted treatments for certain diseases for both women and men”, says Clair.

This has meanwhile also been acknowledged by important research funding agencies. At the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), the world’s biggest funder of medical research, applicants have to state the sex of the animals used in their experiments, and they have to justify their decision. In Switzerland, the SNSF does not yet have any such requirements, as is confirmed by Irene Knüsel, the head of its Biology and Medicine division. However, it has set up a new funding instrument for cross-border collaboration, SPIRIT, which is open to researchers from absolutely all disciplines, and includes a focus on projects that investigate gender aspects.

Things are also happening elsewhere. Today, Switzerland has two professorships in gender medicine. One is held by Clair at the University of Lausanne, the other by Catherine Gebhard, a cardiologist at the University of Zurich. The Universities of Bern and Zurich are jointly offering a course for a Certificate in Advanced Studies (CAS) entitled ‘Sex- and Gender-Specific Medicine’. “We are going in the right direction”, says Gebhard, “but we have a long way to go before a gender-sensitive approach is adopted widely in the medical world”.

Study diversity is a problem

Therapies and drugs are primarily developed by the pharmaceutical industry. But for a long time, the industry largely excluded women of childbearing age from clinical trials. In fact, several scandals gave them no choice but to exclude women, out of fear of putting unborn children in danger – such as the tragic case of the tranquiliser thalidomide in the 1960s, which caused thousands of children to be born with deformities.

It took a long time before regulatory authorities and ethics committees were again willing to approve studies with women, and even longer before they began to insist on them. But it was only in the 1990s that evidence began to accumulate that gender has a significant impact on the efficacy and tolerability of drugs. Today, for example, Swissmedic – the Swiss supervisory authority for drugs and medical products – explicitly requires both sexes to be represented in studies, in order to correspond to the actual distribution of a disease. There are specific scientific guidelines for including pregnant women that are intended to ensure the safety of unborn children.

Stefan Frings is the Global Head of Medical Affairs at Roche Pharma. He says: “In our clinical trials, we aim for a distribution of patients that is representative of the population that we can later expect to be treating. We almost always succeed in terms of gender distribution”. However, he admits that there is another goal that is more difficult to fulfil: a sufficiently high level of diversity among female study participants. “In breast-cancer studies in the USA, it’s not easy to find enough African-American women”, he says. “Often, the reason for this is that this population group is underrepresented in the institutions that we use as our study centres”. Nevertheless, researchers are aware that certain forms of breast cancer reveal ethnicity-based divergences, both in the initial diagnosis and in the prognosis.

There is a further problem, says Gebhard: “Often, a study’s exclusion criteria can indirectly result in too few women participating. Heart diseases affect women at a higher age than is the case in men. But you can hardly find anyone over the age of 80 in the relevant studies”.

Insufficient practical data

Therapies can also be adjusted after they have been approved. In such cases, healthcare data are of crucial importance, especially data that have been collected as a matter of routine. Ideally, they should provide information on gender-specific differences – whether about the course of an illness, side effects, or who makes use of which preventive check-ups.

In theory, there is a huge potential for gender medicine in such data. But the reality in Switzerland is not quite so encouraging. For example, even the gender distribution of Covid-19 patients in intensive care units across Switzerland can only be deduced from the routine data after a significant delay – and it is not even possible for all patients. “What we do know about this right now has had to be compiled in a highly time-consuming fashion”, says Gebhard.

The problem is that a lot of the routine data collected in Switzerland is not gathered or compiled according to uniform standards. This is different from the UK, for example, which is regarded as a pioneer in the field. Thanks to well-organised data infrastructure, researchers there are able to retrieve the up-to-date gender distribution in intensive care units, and can also analyse it in relation to other factors such as prior illnesses or age.

This is the state of affairs currently aspired to by the Swiss Personalised Health Network (SPHN), which compiles data from five university hospitals across Switzerland. This could make detailed studies possible that would relate gender to all manner of other clinical factors. But according to Katrin Crameri, the director of the SPHN Data Coordination Centre, SPHN data have not so far been used for research projects in gender medicine. And we cannot expect to get a body of data of similar quality any time soon in the biggest field of medical practice, namely outpatient care.

It is therefore difficult to assess just how much gender medicine research finds its way into medical practice; conversely, it’s just as difficult to tell where medical practice really needs corresponding research. But the goal is clear: “In future, we want to anchor a gender-specific perspective more firmly within existing structures”, says Gebhard, “with institutes of our own, in the funding criteria applied by the SNSF, and in the guidelines issued by the professional associations”.