RESEARCH MISCONDUCT

The science police

Some individuals have taken it upon themselves to root out fraud in scientific publications. But are they really a force for good?

You need a watchful eye to recognise manipulations of scholarly data. | Photo: Colin Lloyd/Unsplash

In July 2015, ETH Zurich announced that one of its professors had breached its guidelines on research integrity by publishing papers that contained deliberately altered images. The news created headlines not least because the researcher in question – the plant scientist Olivier Voinnet – had been something of a rising star. Although ETH concluded that the image manipulation did not impact the scientific conclusions of the papers in question, it nevertheless admonished Voinnet and placed him under supervision.

But while the controversy centred on Voinnet, it also drew attention to the broader issue of how dubious or fraudulent research should be brought to light. In this case, it wasn’t university administrators, journal editors or research funders who issued the alert, but anonymous e‑mailers who contacted academics at ETH and elsewhere, pointing them to posts on the online research forum PubPeer.

PubPeer enables users to post comments on apparently problematic publications. The fact that many of those users are anonymous had led some to accuse the website of allowing zealous, even vindictive individuals to denigrate the work of well-meaning scientists. Indeed, Voinnet himself describes the site as a “necessary evil” that helped him and his colleagues correct the scientific record, but which he still regards as “inadequately managed and moderated”. Others, in contrast, see the site as a vital tool for whistle-blowers – that new breed of independent watchdog aiming to keep scientific research on the straight and narrow.

One enthusiast of such scrutiny is Edwin Constable, a chemist at the University of Basel, who recently led a group of experts in revising Switzerland’s scientific code of conduct that is published by the Swiss Academies of Arts and Sciences. Constable acknowledges that many of his peers see things differently. He also points out that allegations of misconduct have sometimes turned out to be wrong. But he says that, in a “great many” cases, the whistle-blowers have been vindicated, and he argues that the renewed institutional focus on research integrity might not have happened without them. “Unrestricted public oversight is generally to the benefit of science”, he says.

‘Retraction Watch’, which is based in the USA, is another well-known website dedicated to research integrity. Run by the journalists Ivan Oransky and Adam Marcus, the site provides daily reports on papers retracted by journals that often do little to publicise or explain the removal. For Oransky, full transparency in the scientific process means informing not just other specialists about faulty papers, but also the general public, because it can then apply the necessary pressure. “Insiders on their own are unlikely to change things”, he says.

Scientific sleuths

He and Marcus also maintain a database of retracted papers. By the end of 2021, they had notched up 31,000 entries. Oransky insists they don’t actively look for research misconduct, but leave that work to the scientific “sleuths” instead.

The British anaesthetist John Carlisle, for example, has made a name for himself by using a certain type of statistical analysis to identify suspect data from clinical trials. Debora Weber-Wulff is a professor of media and computing at HTW Berlin who investigates academic plagiarism. And the Dutch biologist Elisabeth Bik has enjoyed considerable success in spotting suspect images in scientific papers.

Bik worked on microbes at Stanford University in California for 15 years. Then, in 2013, she began trawling through publications for signs of conflicts of interest, plagiarism, and especially the duplication and manipulation of images. She sometimes works from scratch, and at other times on the basis of tip-offs. She then posts the results of her work on Twitter and on her blog ‘Science Integrity Digest’.

Bik agrees that she works essentially as a detective, following leads and sometimes establishing a pattern of behaviour that suggests systematic manipulation on the part of specific researchers. But she does not see herself as a law enforcer. Instead, she tries to limit herself to more-or-less objective comments on problematic papers.

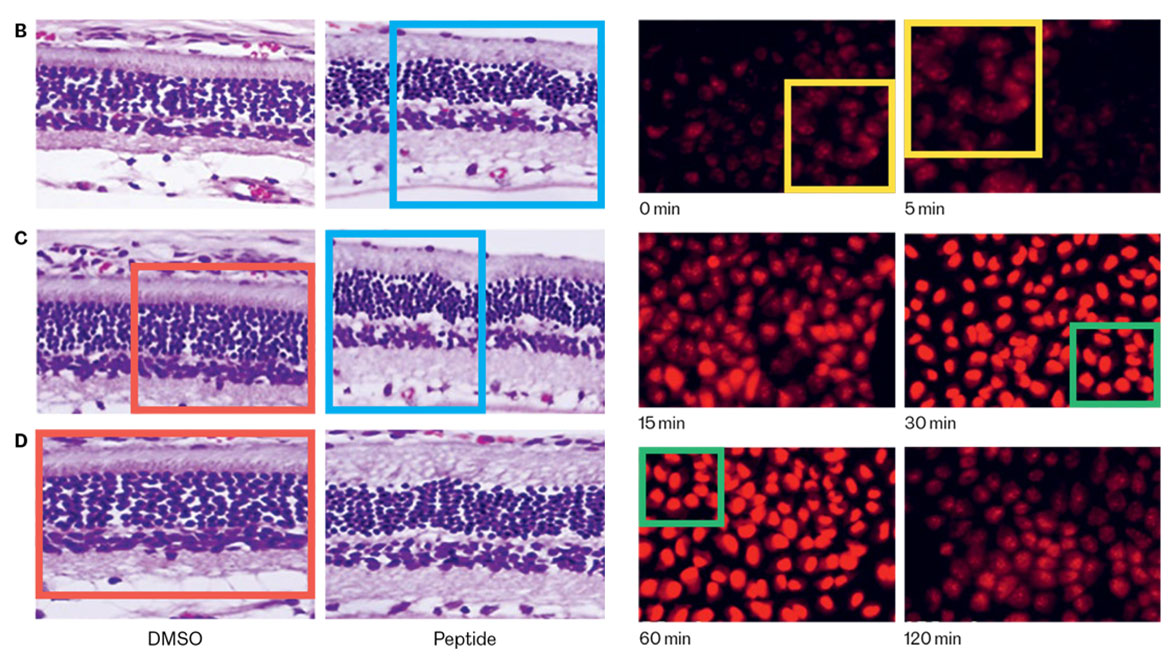

Two manipulations in two different specialist journals. The content within the identically coloured boxes is the same in each case, though the images are supposedly of different samples (on the left we see the retina of mice, on the right human cancer cells). Since these images are slightly distorted, it is difficult to imagine that these duplications occurred in error. The biologist Elisabeth Bik made these cases known on the Pubpeer platform. The article in which the left-hand images appeared has since been withdrawn; the article with the images on the right has not (as of January 2022). Left-hand image: S.-E. Cheng et al. (2017), right-hand image: G. Bhanupraksh Reddy et al. (2017), coloured boxes: Elisabeth Bik

Not everyone shares this approach. For the last six years, the German biomedical researcher Leonid Schneider has been writing his blog ‘For Better Science’ to expose what he calls “corruption” among “the scientific elite”. He regards himself as an ‘activist’ among science journalists, and launches fierce attacks on those he deems to have committed a transgression. Some he has described as “crooks”, “ruthless quacks” or “academia’s ugly brown backside”. But he insists that these labels do not detract from the substance of his analyses. “Very few people tell me my facts are wrong”, he says, “though they complain about my attitude”.

A career as an independent watchdog is not for the faint-hearted. Schneider’s confrontational style has antagonised many, and in some cases it has landed him in court. Indeed, his fines and legal bills have become so high that he has only managed to remain afloat, he says, thanks to large donations from his readers. But this work rarely pays the bills, even for those whose approach is more diplomatic. Oransky points out that he and others like him are volunteers who get paid little or nothing for their efforts.

Fighting for systemic change

There are occasions when scientists have uncovered misconduct in their own lab. This was the case, for example, when the neuroscientist Ralf Schneggenburger and his colleagues at EPFL published a paper about fear learning in Science in 2019. After re-analysing brain-activity data from mice to obtain finer-grained results, he and two of his co-authors discovered to their shock that the paper’s first author had falsified much of the data to exaggerate the effect. Schneggenburger thereupon contacted the journal and the Dean of his faculty, and retracted the paper shortly afterwards.

Such self-reporting, however, appears to be quite rare – prompting the question as to who should be scrutinising the vast research output of academics. Oransky says that universities themselves can’t be trusted, given that faculty members often attract considerable sums of grant money. The people who should be on the lookout for fraud and misconduct, he argues, are the publishers.

Bik, however, says that journals often fail to follow up on the leads that they are handed. Of the roughly 5,000 dubious papers that she has uncovered, she estimates that only about 35–40 percent of them have been retracted by the journals, or had corrections issued. She believes that this lack of action points to a conflict of interest, either because papers have been written by authors close to journal staff, or because the publishers demonstrate an unhealthy concern for citations. She adds that there have been efforts to improve quality control, with some hiring staff to oversee research integrity and to check images.

Bik nevertheless reckons that a real overhaul will likely “take years”. Ideally, she argues, national or even international organisations that are independent of both publishers and universities should be charged with overseeing scientific integrity. Sweden recently set up just such a body. But Constable has his doubts as to how wise or useful it would be to institutionalise the function of a watchdog. Such a move might increase the quantity and efficiency of integrity checks, he argues, but would come with its own drawbacks. “It may lead to box-ticking while losing the spontaneity and engagement of the community”, he says.

For the moment, it looks like the independent watchdogs will continue to shoulder much of the burden of identifying spurious research – attracting both praise and rebukes in the process. Battle-hardened Schneider says that the costs he has incurred haven’t made him regret embarking on his unusual line of work. He sees himself as defending the interests both of the public at large and of those scientists who are afraid to speak out against powerful colleagues. “My goal is to change the system”, he says. “Not by myself, but by giving a voice to the people who want to do it”.