MICROBIOME

What bacteria can do for us

The diversity of our body’s microscopic inhabitants is increasingly proving to be of practical use. We offer an overview of various possible applications of the microbiome.

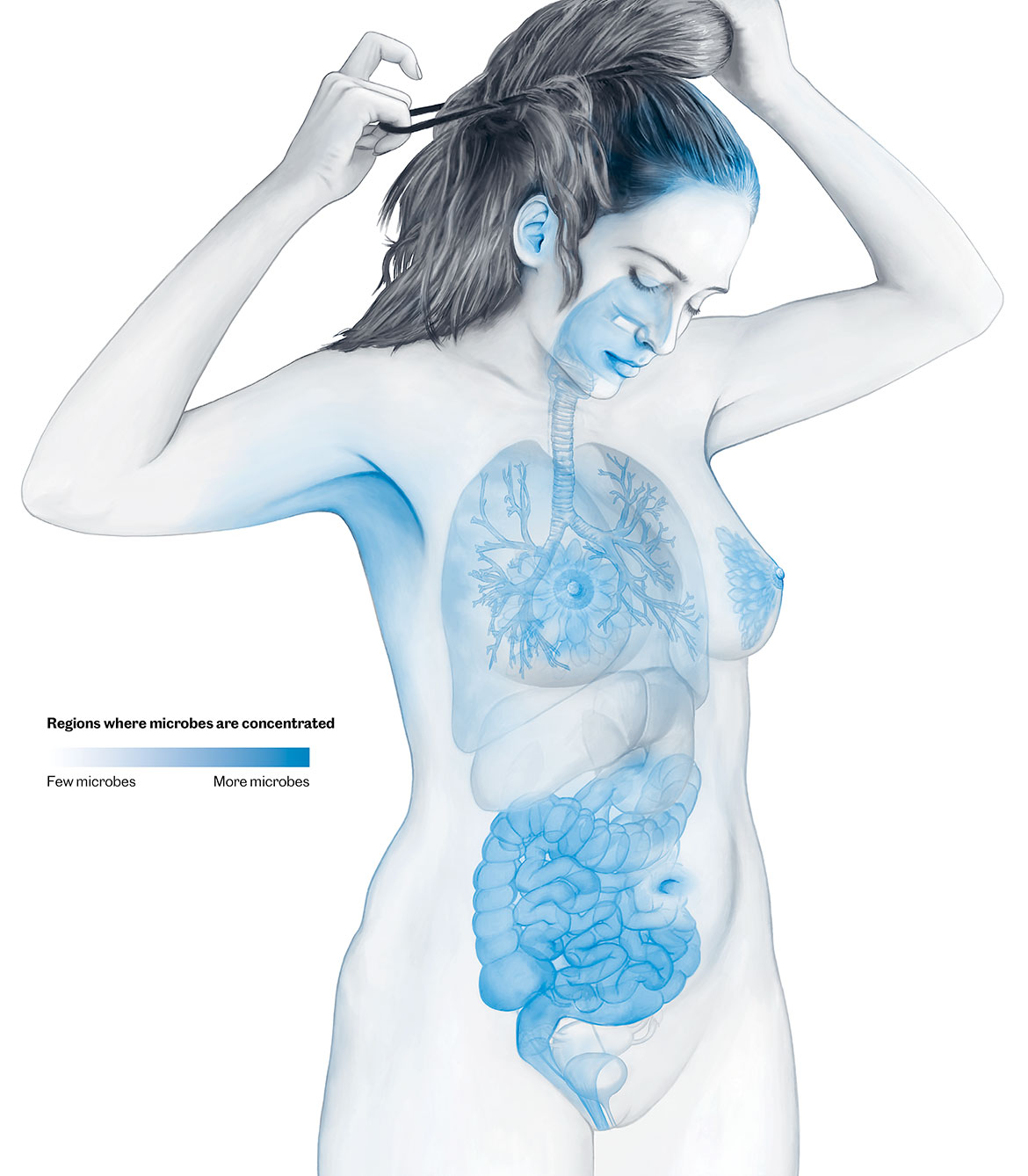

Countless microbes can be found on our skin and mucous membranes. But most of them colonise our intestine. The bacteria, yeast fungi, other single-cell organisms and viruses in our intestine weigh over a kilogram. They have been the object of intensive research for some time now. But research into the microbiome of other parts of our body is only just beginning. Newborn babies, for example, receive their first important mixture of microorganisms from their mothersʼ vaginas and then through breastfeeding. But the mouth, respiratory tract, hair roots and urinary tract also all have their own microbiomes. | Illustration: Oculus

Swallowing stool

Swallowing faecal matter as a medical therapy doesn’t sound very appetising. But people who suffer from severe diarrhoea and abdominal pain due to recurring infections with the bacterium Clostridium difficile are glad of it. When they swallow capsules with stool extract, this leads to a permanent cure in 95 percent of cases, says the infectious diseases specialist Benoît Guery from the University Hospital of Lausanne (CHUV). With antibiotic treatments, the success rate is only about 30 percent.

In Switzerland, only CHUV has a licence to carry out so-called faecal microbiota transplants. The idea behind it is this: the bacterium C. difficile spreads in the gut of people whose microbiome has been impoverished by previous antibiotic treatments. By swallowing a stool sample taken from a healthy person, the gut is re-colonised by a diverse community of microbes, restoring homeostasis.

“In the past, desperate patients found themselves compelled to organise stool samples for themselves, and prepare them with a kitchen blender”, says Guery. That dangerous practice is now a thing of the past. Potential donors have to pass health checks to ensure that no diseases are transmitted to the recipients, and the preparation of the capsules is also standardised. Faecal microbiota transplants are also being discussed as a possible therapy for other diseases associated with the microbiome, e.g., inflammatory bowel diseases and neurological diseases such as autism. However, evidence on their efficacy is still lacking.

We need a Noah’s Ark for the microbiome

A seed bank already exists on Norway’s Spitsbergen. And a similar ‘treasure chest’ will soon be created in Switzerland. But instead of seeds, researchers want it to house samples of the human microbiome from all over the world. This is the plan of the international Microbiota Vault initiative, in which Swiss institutions are also playing a significant role. The aim is to preserve the diversity of the human microbiome for posterity before it is too late. For several years now, there have been signs that we are experiencing an impoverishment of bacterial species, especially in the intestinal flora of people living in industrialised countries. The culprits are probably our use of antibiotics, our unbalanced diet and our lack of contact with nature. “At the same time, we are seeing an increase in chronic diseases such as allergies, obesity and diabetes”, says Pascale Vonaesch of the University of Lausanne, which is one of the primary institutions responsible for the pilot phase of the initiative.

Using 2,000 stool samples, the researchers in the pilot project are currently developing methods to preserve and reactivate microbiomes. “This is far more challenging than with seeds, because we are dealing with complex mixtures of bacteria that survive under different conditions”, says Vonaesch. His team is still hunting for an old military bunker to house their refrigerated containers with the samples.

Can microbes solve crimes?

A murder has happened; the police have a suspect. But the DNA analysis of the saliva found in a bite wound does not help, because the suspect has an identical twin with identical genes. Can the two perhaps be distinguished by the bacterial composition of their saliva? A team from the universities of Lausanne and Fribourg has looked into this hypothetical case.

In a study of 30 pairs of identical twins, they found that each sibling has a unique combination of oral bacteria. The problem is that the individual microbiome changes over time, for example, when someone alters their diet. And there is also some overlap between siblings. So sophisticated statistical methods are needed to calculate reliable probabilities. “In principle, this method is suitable for forensics”, says the team member Laurent Falquet. “But it shouldn’t be used yet as sole proof of someone’s guilt”.

Bacteria controlling the brain

Our intestinal flora is jointly responsible for numerous brain diseases including depression and schizophrenia. But there is now hope that changing the nutrition of those affected might also improve their condition. “Often, however, there are hardly any clinical studies about this, and we know too little about the mechanisms involved”, says Dragos Inta, a psychiatrist at the University of Fribourg.

He is studying why roughly a third of people with depression also suffer from severe obesity. “Neuroinflammatory processes play a role in this, which is not the case with classical depression”, says Inta. Messenger substances produced in the abdomen are presumably responsible for triggering chronic inflammation in the brain. Together with an international team of researchers, he is now investigating whether a low-carbohydrate diet might help to alleviate both obesity and depression.

Social status shapes the microbiome

It is well known that our health is strongly linked to socio-economic factors such as income and education. However, we don’t know much about the biological mechanisms that are behind this. “One possible link is the composition of the microbiome”, says Stéphane Cullati, a health sociologist at the University of Fribourg. His hypothesis is that social variables determine our nutrition. This in turn shapes the gut microbiome, which has been proven to influence our health.

In order to confirm such correlations epidemiologically, Cullati uses large datasets from studies in which both the diversity of the intestinal microbiome and key social data were collected – such as in the American Gut Project with its more than 10,000 participants. Initial analyses show that a higher level of education correlates with a greater microbial abundance. “It is possible that these people earn more, can afford better food and therefore have a healthier microbiome”, says Cullati. But he adds that it is too early for definitive results.

Probiotic support for medicines

The pills that we swallow are often attractive to bacteria. “There have long been anecdotal reports that our intestinal flora can influence the impact of certain drugs, such as digitoxin”, says the Swiss microbiologist Michael Zimmermann, a group leader at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Heidelberg. He has now undertaken the first-ever systematic investigation into whether common intestinal bacteria can modify medicinal agents – and if so, how.

His findings show that two thirds of the 271 drugs he tested were actually transformed into other substances. “These effects ought to be considered when developing, prescribing and dispensing drugs”. He believes that it might become possible to use probiotic foods or stool transplants to adapt someone’s intestinal microbiome to specific drugs in a personalised way.