Feature: Evaluating the evaluation

In the beginning was subjectivity

Usually, only two researchers are appointed to peer-review a paper, and they do so independently of each other. Peer review can’t function properly without this element of subjectivity, writes Judith Hochstrasser, joint Editor-in-Chief of Horizons.

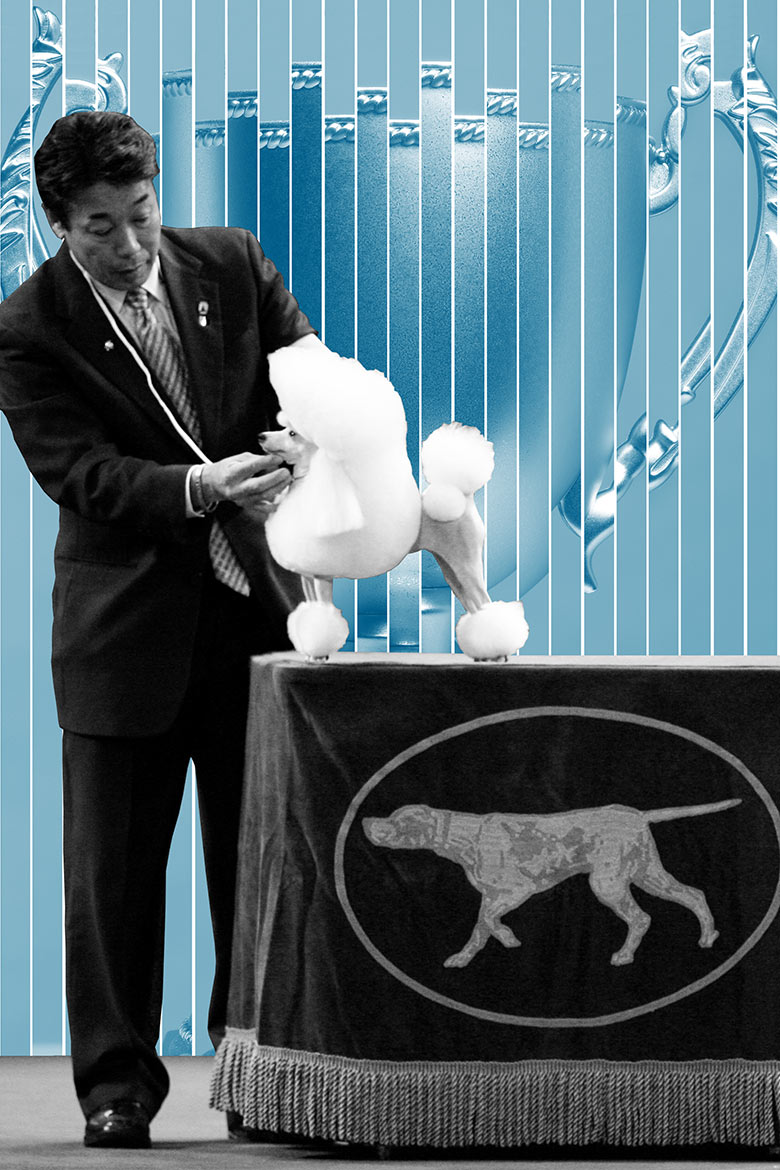

Beauty lies in the eye of the beholder. But there are countless competitions to judge ‘the fairest in all the land’. Even dogs can become an object of human evaluation. | Photo: Keystone, Getty Images

How do you think peer review functions? Perhaps someone submits an article to a scholarly journal, and it’s then given to dozens of expert colleagues tasked with undertaking an in-depth critique. Each of them fills out a predetermined grid with the relevant criteria. Their assessments are compared, good points and bad points assessed and, ultimately, it’s determined what the paper lacks, what needs to be changed, or why it has to be rejected – and all, one might imagine, through a process of quantitative analysis. That’s how an ideal peer-review process might look if it were based on truly scholarly criteria.

But the reality is quite different. It’s the assessments of individual reviewers that determine whether or not an article is accepted for publication in a scholarly journal. Usually, only two researchers are appointed to evaluate a paper that’s been submitted, each of them working alone. One of the editors of the journal in question then assesses the comments of these two reviewers and decides whether or not to publish.

Evidence should be as statistically meaningful and as unbiased as possible. So it’s actually astonishing that our scientific system – which is geared to producing and analysing masses of unbiased statistical data – would be unable to function without this subjectivity at the heart of it. Attempts are naturally made to circumvent this subjectivity, such as by using public peer reviews or artificial intelligence – you can read more about such evaluation processes in our Feature articles in this issue of Horizons. But all the same, subjectivity remains the prevailing principle when peer-reviewing research. Some complain that it shouldn’t be so and that it’s simply wrong.

But we have to affirm that we need this subjectivity. The reason is simple: for all its flaws, no better system exists. This is especially true because the peer-review process means that everyone can theoretically be both the evaluator and the person being evaluated. This underlying fairness in the system naturally ought to be applied with greater consistency – which would mean ensuring as many different researchers as possible engage in regular peer-reviewing, including junior researchers. It would mean that the evaluation process would no longer be confined primarily to a specific group of experienced researchers. If a maximum of varied, individual opinions were to come together, the result would be an overall evaluation that is less biased.