Feature: Start-ups in business heaven

In the land of spin-offs

The path from the lab to your clients is a long one. People who set up their own companies need money, entrepreneurial expertise and a good network. We offer a glimpse into the funding ecosystem of Swiss spin-offs.

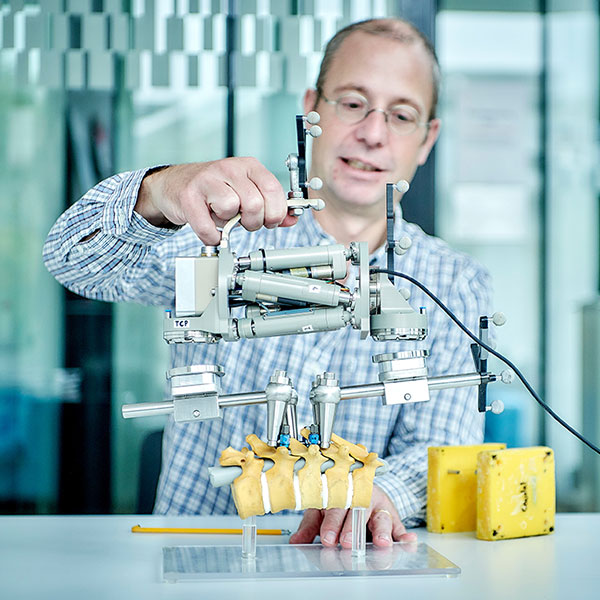

A start-up is nurtured in an ‘incubator’. It receives funding, advice, contact with investors, premises for research and space for its development. | Image: Lucas Ziegler

“There’s nowhere else where you have so much influence as an individual”, says Betim Djambazi. He’s a mechanical engineer at ETH Zurich, and he’s planning to found a spin-off company together with three of his friends. Their product is a snake-like robot called ‘Roboa’ whose shape and means of propulsion enable it to reach inaccessible places, e.g., inside narrow pipes. Their team developed the technology four years ago as part of their Bachelor project. “We wanted to make something that would work in real life too, not just in the lab”, says Djambazi. But none of them contemplated setting up a spin-off company back then. “We were just having fun, getting a technology up and running that hadn’t existed before”.

Sowing creativity, reaping spin-off benefits

That’s exactly how entrepreneurship often begins, says Frank Floessel, the head of ETH Entrepreneurship: in a playful context. ETH Zurich even has its own premises for promoting creative collaborations, i.e., the Student Project House. “It’s a place where students and project teams can simply tinker with an idea and see how far they get”, he says.

Floessel’s team is tasked with providing support for prospective spin-offs wherever they need it. “People often come to us early on in the process, when they’re working on something that they think could be commercially interesting”, says Floessel. “We then accompany them along their path of translating their scientific idea into a business prospect”. This can include coaching them directly and persuading them to attend the right courses and workshops and to participate in funding competitions. It all depends on how far an idea has already progressed, and how much entrepreneurial knowledge they already possess.

The Roboa team, for example, were the first to apply successfully to ‘Talent Kick’ – a programme that provides budding entrepreneurs with an initial small grant plus some coaching, and also brings them together with potential co-founders. In February 2024, the Roboa team also secured a ‘Pioneer Fellowship’, an incubator grant reserved for members of ETH Zurich. “Its aim is to provide prospective company founders with money and 18 months to work on their technology, developing it to a point where it can find a market”, says Floessel. The process of making lab-based technologies fit for the marketplace usually requires a good deal of time.

Initial money with no loss of control

Many other universities and organisations offer competitions for this kind of funding, both for existing and prospective spin-offs. For example, there’s Venture Kick – a competition that takes place over several rounds that’s open to members of all Swiss universities. But perhaps the most important role in this funding system is played by Innosuisse. It’s a federal agency that specifically finances discoveries and technologies from the Swiss research landscape in order to turn them into marketable products that can generate jobs and advance society. According to Floessel, spin-offs that succeed in such funding competitions can receive up to a million francs. When compared to the process of seeking major investment from a venture capitalist, the advantage of these grants is that the founders do not have to surrender any shares in return for funding, but retain full control over their company.

The Roboa team is also benefiting from this. Thanks to their Pioneer Fellowship, Djambazi and his colleagues now have the time to work further on their third prototype. “The robot works – that we know from our tests”, says Djambazi. But thus far, it only works when the development team uses it, for they are aware of all its teething troubles. “Now we want to advance it to a point at which it can also work reliably in the hands of future customers”.

- Illustration: Swiss Startup Radar 2018/2019

And yet it takes more than just money to launch a spin-off company successfully. “First of all, we have to reach out to researchers to show them how founding their own company is a feasible career path”, says Floessel. According to a survey of almost 7,000 Swiss students conducted in 2021, between one and two percent of them had already founded a company, and around seven percent were involved in creating one at the time. So Floessel’s team regularly organises events at which the founders of established spin-offs talk about themselves and their companies. “This provides potential founders with role models: people of whom they can ask questions, and who offer proof that things really can work out”.

A whole funding ecosystem

Spin-off founders have a whole network of support programmes at their disposal, all with highly promising names. One of the most important is ‘Startup Campus’, a consortium of various universities, technology parks, innovation parks and other support organisations. It offers training and support programmes known as ‘incubators’ to those involved in start-ups. “We want to reach out to potential founders and help them through the whole process”, says Matthias Filser, the head of Startup Campus and of the Entrepreneurship centre of ZHAW – Zurich Universities of Applied Sciences and Arts. For example, they help start-up teams to develop a business concept and a marketable product, and assist them before they set off on their pursuit of possible investors.

According to Filser, one of the most important steps is to guide start-up founders into a dialogue with potential end users, so that the latter may see what kind of products or services would provide them with added value and which they might be willing to fund. Overall, the Startup Campus has trained some 3,700 prospective company founders since 2013, and the start-ups benefiting from their support have altogether raised more than CHF 50 million of investment capital.

There is a total of roughly 70 organisations in the Swiss spin-off ecosystem that support budding university entrepreneurs by providing funding, training opportunities and coaching. “When it comes to supporting spin-offs all the way up to finding an investor, Switzerland is very well positioned in an international comparison”, says Filser.

But smaller universities also generate spin-offs. For example, the University of Fribourg has a Knowledge and Technology Transfer Service to support prospective company founders. It’s headed by Valeria Mozzetti Rohrseitz. Early on, as soon as a potential start-up team submits its patent application, Rohrseitz and her colleagues establish close contact with its members, often supporting them over several years. They offer a proof-of-concept grant to enable students and employees to prepare their technology so that they can compete for prizes and funding of the kind provided by Innosuisse. They also maintain a partnership with Friup, the cantonal advisory agency for start-ups.

Spin-offs still a male domain

It’s important to Rohrseitz that there should be equality between men and women, regardless of issues of family planning. And this is by no means a given. Innosuisse, for example, will pay salaries but not the equivalent of the cantonal family allowances. “That’s why we at the University of Fribourg decided to assume that responsibility” says Rohrseitz. “We don’t want company founders to be placed at a disadvantage just because they happen to be parents”. Regrettably, the situation in this regard has barely improved since she founded her own first spin-off company, 20 years ago. “This is still due to the way people perceive things in society. It’s never an issue if a man founding a company has a kid or wants one; but it’s an issue if the founder is a woman”.

In general, Rohrseitz advises founders that they shouldn’t try to do too much at once. They should rather start by placing their technology on a solid footing, and exchange ideas with others who are in the same boat. Back at ETH Zurich, Floessel agrees. “Companies learn the most from what other companies have already experienced. That’s because they generally find themselves facing the same questions and problems. For example, there might be disagreements among the founders, then there are the challenges you face when you enter the market, and when you’re hunting for investors”.

This is why ETH Entrepreneurship regularly organises events – with partial funding from UBS – where spin-off founders can exchange ideas with each other and also get to know potential investors. From Floessel’s point of view, it’s obvious that the bank can provide the funds necessary to hold more events, and that it also has a valuable network of potential investors. Other funding pipelines also work with banks. For example, ZHAW’s Runway Incubator has a partnership with the Zurich Cantonal Bank.

Spin-offs as a viable career path

ETH Zurich has up to now generated more than 580 spin-off companies. Several of them have meanwhile become internationally established and are listed on the stock exchange.

The second-largest Swiss generator of university start-ups is EPFL, which can also boast over 500 of them. In contrast to ETH Zurich, however, EPFL counts all start-ups that originate there, whether or not they began directly at the university. The other universities in Switzerland produce fewer companies, but some of them are also successful. In many cases, they are based on decades of existing research. “Nobody takes this technology away from you at first”, says Floessel. Once the young companies have found a market for their product, their patent means they’re protected from competition for a good while.

The Roboa team also has good chances of success. Djambazi and his colleagues are already in talks with potential future clients, including companies in the chemical and energy sectors that need to inspect and maintain pipelines. “Up to now, there’s nothing that’s as ideal for this as our robot”, says Djambazi. In a second, future phase, his team also wants to realise its original idea for the robot. This is technologically more complex, as they want to design it for relief operations like helping rescue workers to find survivors in rubble and supply them with water.