ACADEMIC WORLD

Measuring the temperature of science

Confidence in science remains generally high, but academic freedom has been decreasing for fifteen years. We provide an overview.

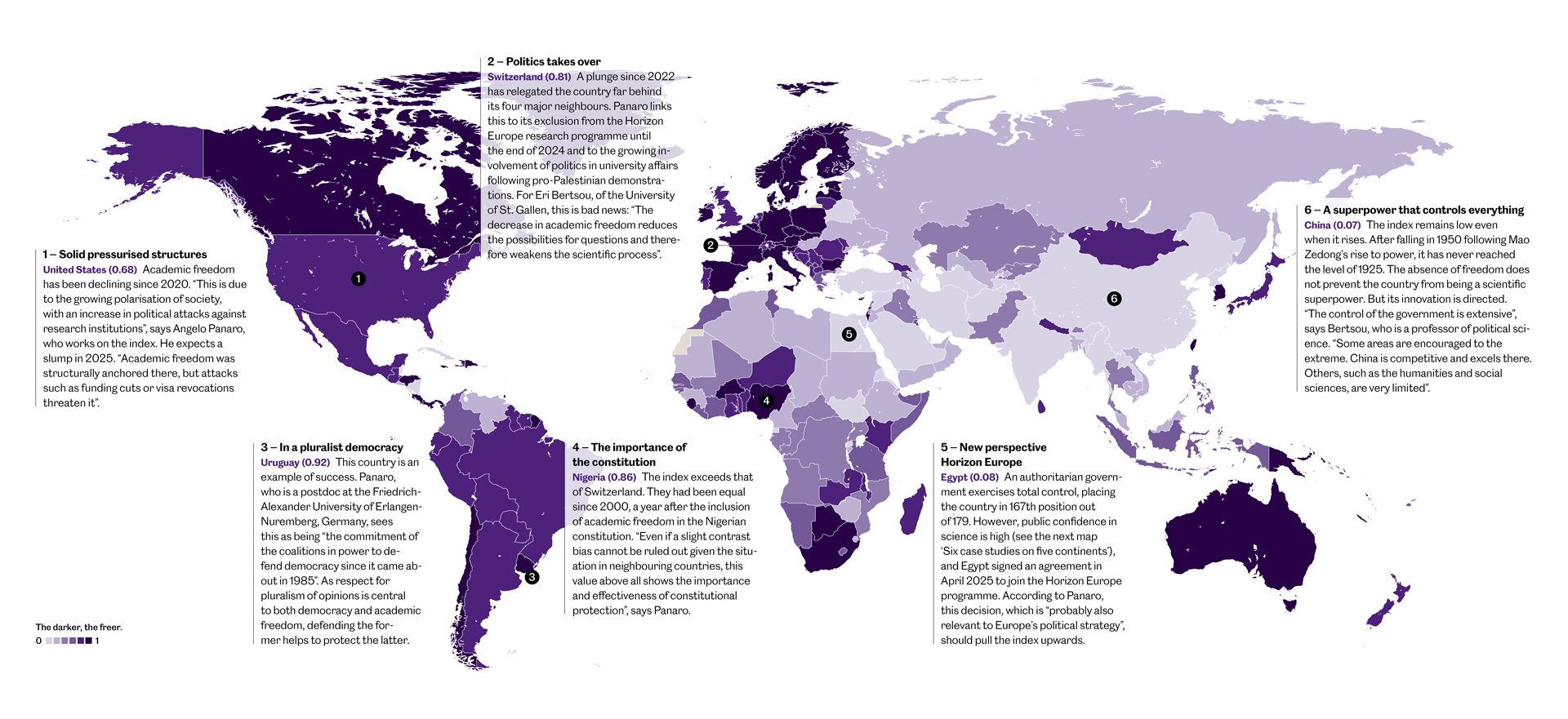

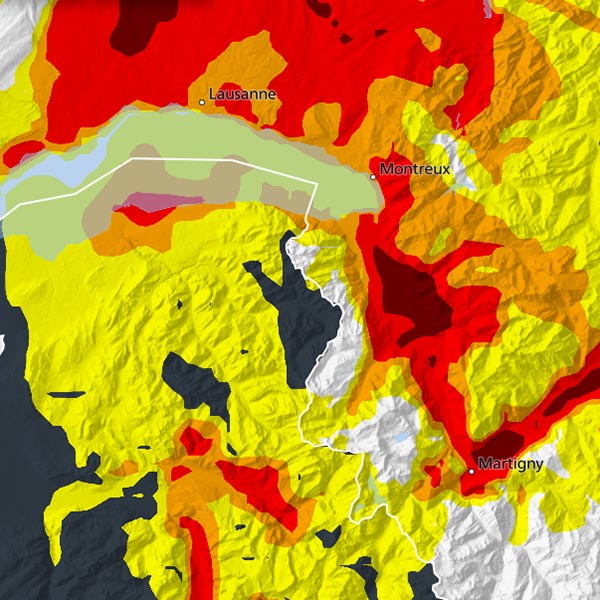

The global academic freedom index 2024

The academic freedom index combines five criteria: freedom of research and teaching, freedom of academic exchange and dissemination, institutional autonomy of universities, campus integrity and freedom of academic and cultural expression. It is based on the analyses of more than 2,300 international experts.

- Six countries and six reasons for a high or low score in the academic freedom index. | Source: The mapping tools and dataset (v15) of the international research project ‘The Varieties of Democracy’ (V-Dem)

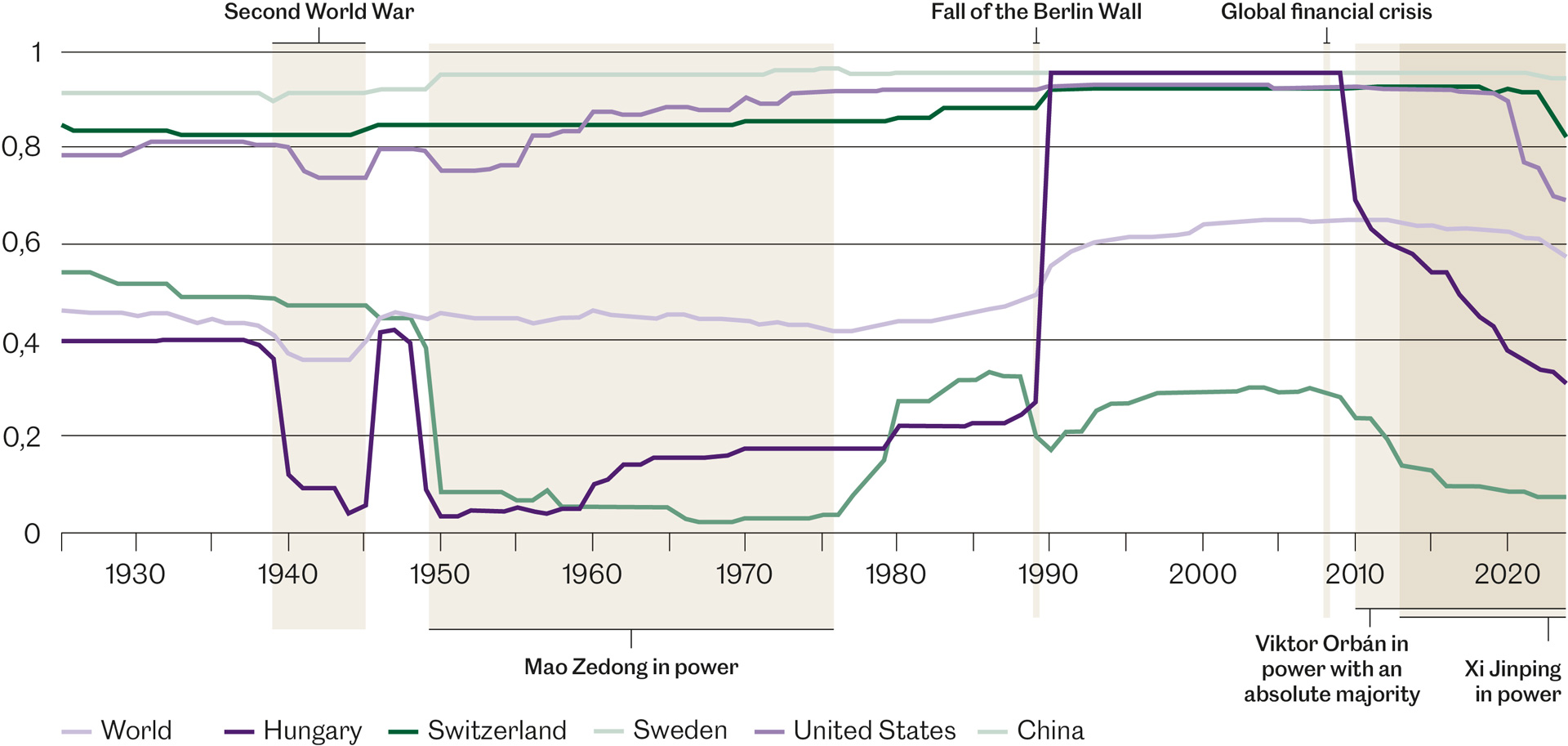

Hungary’s century of ups and downs

The global geopolitical upheavals of a time are directly reflected in academic freedom. Hungary illustrates this correlation well: its academic freedom tracks the Second World War, the authoritarian regime of the Eastern Bloc, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and now the slide into a new authoritarian regime since the beginning of Viktor Orbán’s second term with an absolute majority. Globally, the index has been in continued decline since the economic crisis of 2008. The index has been calculated yearly since 2022 and has been extended retroactively to 1900.

- Geopolitics causes fluctuations in academic freedom. | Source: The graphing tools and dataset (v15) of the international research project ‘The Varieties of Democracy’ (V-Dem)

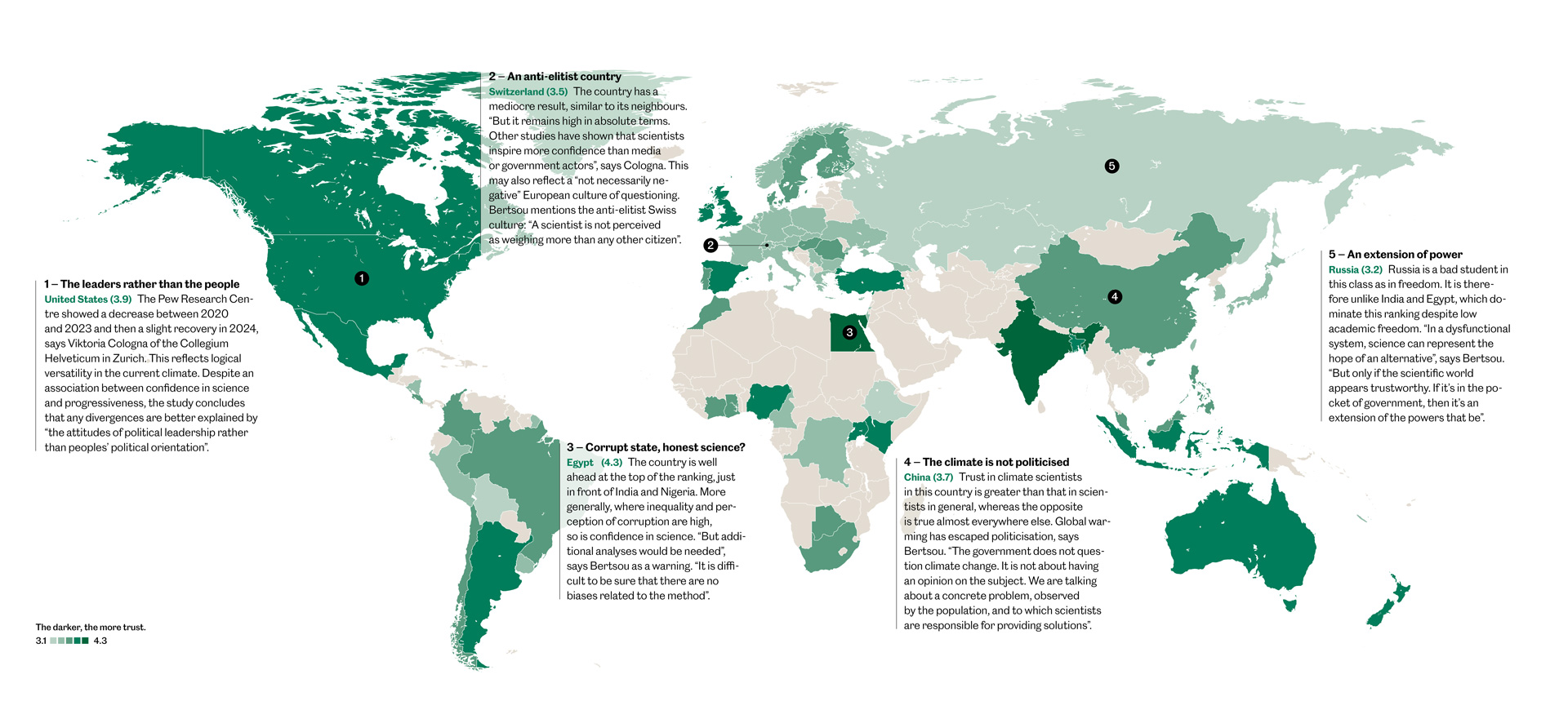

Trust in scientists 2022–2023

Viktoria Cologna and Niels Mede are engaged in research into confidence in science and its perception. They initiated the ‘Trust in scientists and science-related populism’ project at Harvard and Zurich Universities. They had more than 240 experts in almost 70 countries assess the situation in 2022–2023 using a questionnaire. Trust was calculated by combining perceived competence, integrity, benevolence and openness of scientists.

- Six case studies on five continents reveal how we can foster trust in science. | Source: the project ‘Trust in scientists and science-related populism’, V. Cologna et al.: ‘Trust in scientists and their role in society across 68 countries’. Nature Human Behaviour (2025)

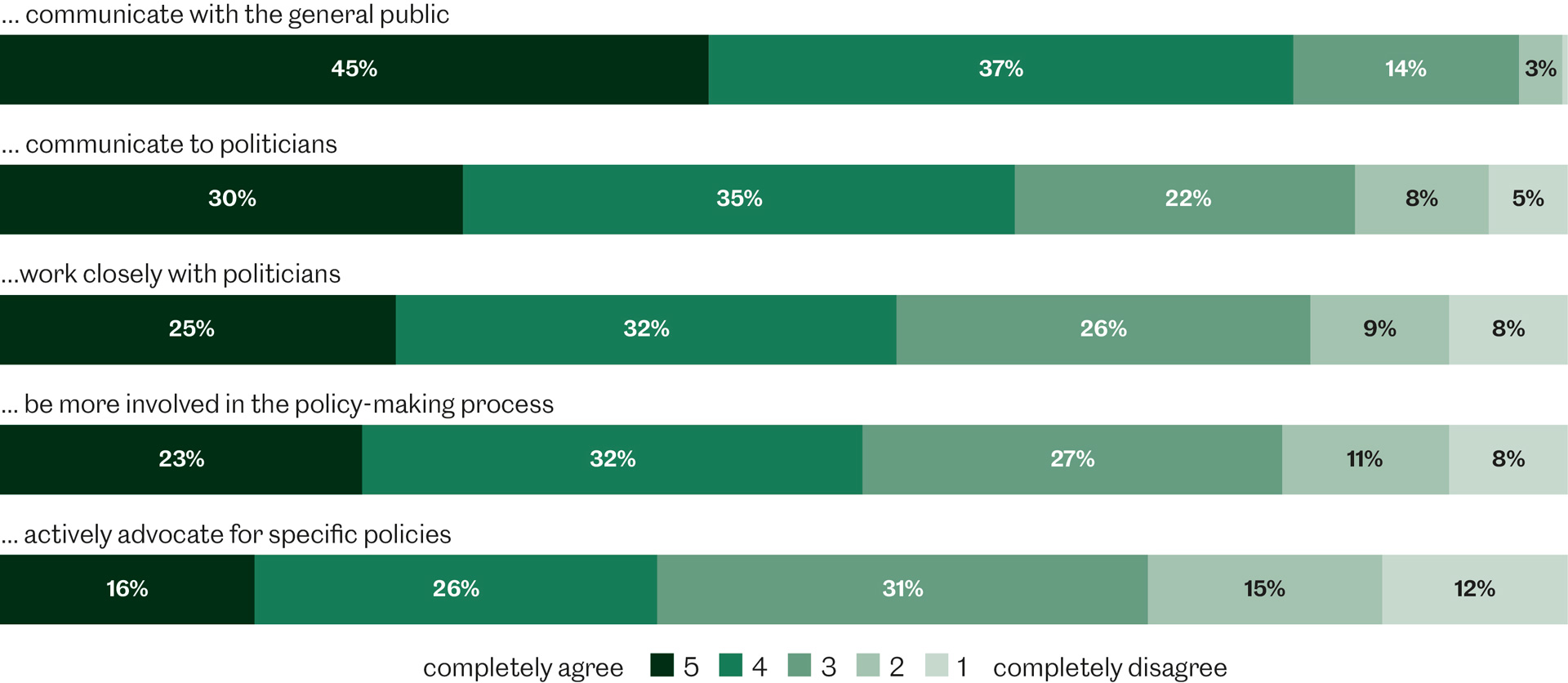

People just want to be informed – without getting politically active!

In Switzerland, 83 percent of those surveyed think that scientists should communicate with the public. But the more things become political, the more this rate decreases: 65 percent of people support communication with politicians, and only 42 percent agree with the idea that “scientists should actively advocate for specific policies”. This lower acceptance rate is seen with nuance by Viktoria Cologna, an expert in confidence in science: “The share of undecided reaches almost a third. So we see that overall, people support the involvement of scientists in politics”.

Survey in Switzerland: Scientists should …

- The more proactive their role, the less approval they get from Swiss citizens. | Source: the project ‘Trust in scientists and science-related populism’

Politically active researchers are popular elsewhere

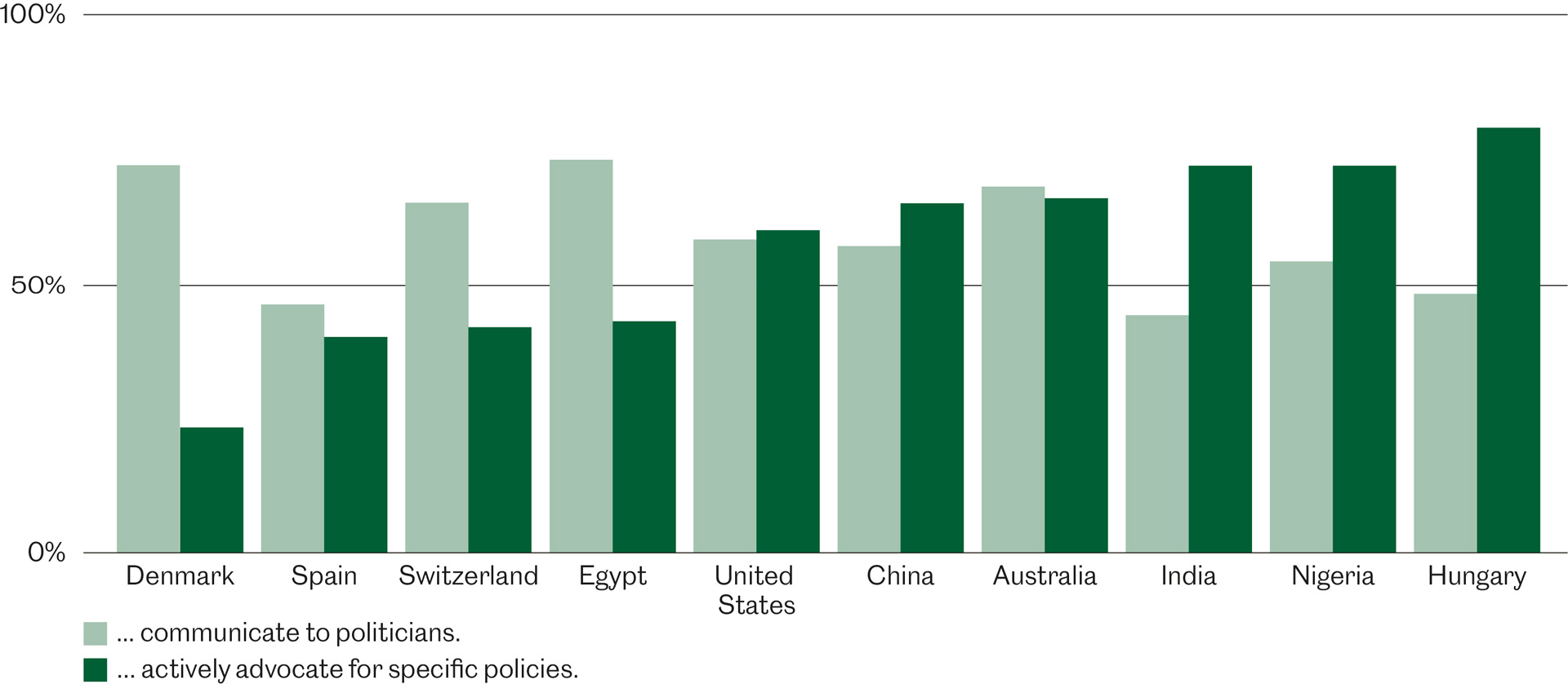

Most European countries, like Switzerland, are for communication, but not very favourable towards scientists engaging in active political advocacy. Denmark is even rather hostile to it, with only 23 percent in agreement. Whereas Egypt ranks on the level of the European countries, Hungary forms a notable exception, for 79 percent of people there are in favour of “active advocacy”. This enthusiasm is shared by the rest of the world, from America to Oceania, through Africa and Asia. “These results are interesting and call for further analysis”, says Bertsou.

Global survey: Scientists should …

- Most Europeans are sceptical about activism in scientists. | Source: the project ‘Trust in scientists and science-related populism’

Infographics: Bodara