Feature: From images to knowledge

We do not see with eyes alone

Noises, memories, our imagination – they all flow into the images that we form of our surroundings. We take a look at the multitudes of interpretative processes that occur between an initial visual stimulus and the image that appears in our minds.

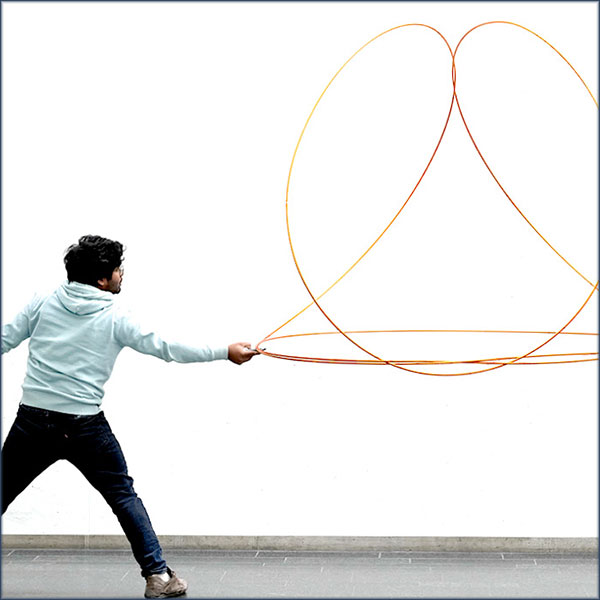

What exactly do we see here? Ambiguous images like these present a problem with too many possible solutions, says neuroscientist David Pascucci. That’s why our brain flips from seeing either a vase or faces. | Photo: MakerWorld

Is it a vase or two faces? On paper, everything stays the same. And yet we suddenly see something completely different. Such ambiguous images prove that seeing is also about interpreting and classifying what we see. Our brain decides what to make of all the lines, dots and shadows that our eyes register. But it can also change its mind in an instant.

This reveals something fundamental about our brain: it hates uncertainty. “Ambiguous images present a problem with too many possible solutions”, says David Pascucci, a neuroscientist at the University of Lausanne. “So, the brain has to make assumptions in order to find the most likely explanation”. This explains how we can ‘switch’ between the two interpretations of the image. Instead of reproducing an intermediary image that would be illogical, our brain searches for an interpretation that is plausible.

“Our sight is often compared to how a camera works. But it’s a false analogy”, says Pascucci. Unlike in photography, our brain does not create for itself a precise image of the reality that exists outside it. Even in sheer anatomical terms, it would be impossible. The retina has many more light sensors than it has nerve fibres for transmitting to the brain the information that it’s received. “This means that the data captured are heavily compressed and the degree of resolution is decreased – and yet we still see an image that goes far beyond mere pixels”, says Pascucci.

What we perceive is ultimately a sophisticated construct that is assembled in the visual cortex at the back of the head. This is where the signals from the retina arrive, are processed and augmented: two dimensions become three, distances are calculated, movements are recorded. Our brain combines what’s available with what it deems plausible, all with the goal of creating a coherent overall picture.

At the mixing console of sensory stimuli

But to achieve this, the brain needs more than what the eyes can show it. The visual cortex also processes information from other sensory channels. “Noises, smells, tactile sensations – they all flow into how we form images”, says Petra Vetter. She’s a professor of cognitive neuroscience at the University of Fribourg and is researching into how multisensory inputs influence our visual perception.

Here, the brain works like a sound engineer at a mixing console, amplifying certain signals but dampening others, all depending on what seems the most sensible decision in the moment. Priority is given to that particular sense that is providing the most reliable information – which usually comes from our eyes, despite their delivering only compressed data. “This is why sight seems to us to be our most dominant sense”, says Vetter. But as soon as visual information becomes unreliable, the brain flicks a switch at lightning speed.

“When we’re in fog, we immediately rely more on our sense of hearing”, she says. “This is because the visual signal is too fuzzy for us to form a usable image of our surroundings”. People who have been blind since birth still have an active visual cortex, for example; it just uses other channels. Their spatial perception is still organised – but it’s based on sounds, touch and olfactory stimuli.

This lightning-fast act of switching channels helps to illustrate how our brain goes about systematically clearing up ambiguities. In doing so, it also draws on our mental archives. Our memories, experiences and expectations help to fill in visual gaps. This is why Vetter believes that the transition between cognition and perception is fluid. “We now assume that our perception of space is created in loops. The brain checks things, compares them and adjusts its information until everything fits together”. It’s an iterative process.

Our imagination is another element that helps this process. “The brain is constantly making predictions in order to construct a plausible representation of our surroundings”, says Fred Mast, a psychologist at the University of Bern and a specialist in mental images. “Our visual sensory processing is far too slow on its own for us to be able to find our way around in the world”. Our imagination therefore also plays a role in our perception and is fed with what we’ve stored in our memory and much beyond it.

The role of our imagination

“We are also able to see things in our imagination that don’t exist”, says Mast. Like a flying camel. “You’ve never seen one, have you? But I bet you have a picture of one in your head right now”. And yet this doesn’t work for everyone. People with a condition known as aphantasia lack the ability to create such mental images. “They can’t imagine objects”, says Mast. “But they can still have a good sense of spatial orientation”. So, while having a visual imagination isn’t an absolute necessity, it does change how we perceive the world.

Between our initial visual stimulus and the image that it triggers in our brain lie multitudes of interpretative processes. The saying ‘I saw it with my own eyes’ should therefore be treated with caution.